Vindicating the New Approach

The unsung benefactors of the new HHS standard

Regular readers of On Drugs know that the recently revealed HHS recommendation puts forward a new legal interpretation for what the phrase “currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States” means. If not, read here.

This test obviously marks a victory for marijuana—assuming DEA adopts it. (That’s not guaranteed, of course.) The lesser heralded benefactors of the test are those now working on state-level psilocybin initiatives.

Avid readers of On Drugs know that I’ve ragged on these initiatives. I won’t rehash my criticisms here.1 Rather, in this short note, I go a different direction. Here, I will explain why folks may want to invest their time and money supporting these initiatives—and on what terms.

A Background of the Five-Factor Test

Before explaining why the HHS recommendation is a victory for the state-level approach, it is important to take a step back and explain why marijuana remains today in schedule I despite state-level legalization. It all revolves around DEA’s five-factor test for “currently accepted medical use.”

The five-factor test is borne out of two parallel proceedings at DEA regarding the scheduling of MDMA, the scheduling of marijuana. and a seminal administrative law case called Chevron and the doctrine it spawned. That five-factor test is:

the drug’s chemistry must be known and reproducible;

there must be adequate safety studies;

there must be adequate and well-controlled studies proving efficacy;

the drug must be accepted by qualified experts; and

the scientific evidence must be widely available

We’ve briefed and written about this decades-old test over-and-over. In brief, through administrative proceedings and multiple court cases, DEA reinterpreted the phrase “currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States” to require the safety/efficacy evidence needed to obtain FDA approval.

Under this test, any attempt to reschedule marijuana in any manner other than FDA approval would be dead in the water. Why? Because DEA has interpreted “adequate safety studies” and “adequate and well-controlled studies proving efficacy” to necessitate the same quantum of evidence needed for FDA approval.

Thus, for HHS to come to any decision that marijuana has a “currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States” — a necessary predicate to rescheduling — it would have to apply a different standard.

Summary of the HHS CAMU Standard

The standard HHS applied is different. It is described on page 25 the documents:

To summarize, for HHS, “currently accepted medical use” is a two-step inquiry.

Is there widespread current experience with medical use by licensed health care providers operating under state-authorized programs where such medical use is regulated by entities that regulate the practice of medicine in these state jurisdictions?

Is there some credible scientific support for at least one of the medical conditions for which the substance at-issue is used?

Application of the Two-Part Test to Psilocybin Initiatives

As I pointed out in a December 2023 filing in my FOIA case, this new HHS standard has implication beyond marijuana:

In the filing, I was referring to the AIMS dispute. But the issue has import beyond the case as well. Put simply, if enough states embrace psilocybin in medical practice in a manner similar to medical marijuana today, psilocybin could be rescheduled short of FDA approval in a manner no different from marijuana.2

Indeed, for these initiatives to deliver on “equitable” and “affordable” promises, rescheduling is important. Beyond the costs of (over-)regulation, a significant impediment to equitable, affordable access to psilocybin is 280E. Rescheduling to Schedule III, of course, would remove that impediment.

So, how can this happen? Let’s work backwards. I’ll start with Part 2: is there credible scientific support for use with at least one medical condition in Part 1 for psilocybin?

CAMU, Part 2

In the HHS recommendation, HHS explains factors that weigh for a Part 2 CAMUU test being met:

1) [F]avorable clinical studies of the medical use of marijuana, although not necessarily adequate and well-controlled clinical studies that would support approval of a new drug application (NDA), have been published in peer-reviewed journals and/or 2) qualified expert organizations (e.g., academic or professional societies, government agencies) have opined in favor of the medical use or provided guidance to HCPs on the medical use.

In contrast, factors that weighed against a Part 2 of the CAMU test finding:

1) data or information indicate that the medical use of the substance is associated with unacceptably high safety risks for the likely patient population, e.g., due to toxicity concerns; 2) clinical studies with negative efficacy findings for the medical use of marijuana have been published in peer reviewed journals; and/or 3) qualified expert organizations (e.g., academic or professional societies, government agencies) recommend against the medical use of marijuana (based on the available data at the time of their position statement).

All this can be distilled down very simply: what does the data say, including data from non-FDA approve clinical trials?

In the case of marijuana, relying on state reporting data from 37 states and some clinical research, FDA found evidence of efficacy. It also said, “no safety concerns were identified in our review that would indicate that medical use of marijuana poses unacceptably high safety risks for the indications where there is some credible scientific evidence supporting its therapeutic use.” Notably, FDA considered a wide-spectrum of evidence in making this assessment, including botanical marijuana but also isolates.

The future case for psilocybin is arguably stronger. Synthetic psilocybin has succeeded in Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials for certain mental health indications, proving safety/efficacy. I don’t believe there is any credible scientific reason to believe that isolated natural psilocybin would perform in a materially different manner from pure, synthetic. Nor do I believe that natural psilocybin (including non-psilocybin alkaloids) would perform in a substantially different matter.

Applying the same analysis as is applied to marijuana in the HHS documents, the evidence supporting use of psilocybin to treat at least one medical condition already appears to be sufficient. The efficacy of psilocybin has been vetted in clinical research. And, many of the safety concerns with marijuana (e.g., smoking/vaping) are absent with psilocybin administration. To be sure, there are psychological safety risks with psilocybin—as there are with marijuana. And, these need to be studied more. But right now, on both safety and efficacy, the evidence appears to be as good as it is with marijuana if not stronger.

CAMU, Part 1

Because there is a good argument that, today, the scientific evidence supporting the medical psilocybin use is sufficient, establishing natural psilocybin as a substance with a “currently accepted medical use with severe restrictions” really hinges on Part 1 of the CAMU standard.

Here is what HHS said with respect to marijuana on that point:

In the evaluation and assessment under Part 1 of the CAMU test, OASH found that more than 30,000 [health care professionals] HCPs are authorized to recommend the use of marijuana for more than six million registered patients, constituting widespread clinical experience associated with various medical conditions recognized by a substantial number of jurisdictions across the United States. For several jurisdictions, these programs have been in place for several years, and include features that actively monitor medical use and product quality characteristics of marijuana dispensed. OASH, through the Assistant Secretary for Health, concluded that, taken together, the findings from Part 1 warranted an FDA assessment under Part 2 of the CAMU test to determine if there exists credible scientific support for the use of marijuana for at least one of the medical conditions identified by OASH under Part 1.

Beyond that, OASH “concluded that HCPs’ clinical experience with the use of marijuana for various medical conditions is of sufficient extent and duration to help evaluate potential clinical uses.” As Shane and I have repeatedly argued, this new interpretation hews closer to the original meaning of the “currently accepted medical use” text.

The first part of the new two-part test gives back what the five-part test took away: a more decentralized vision of what determines “accepted medical use.” Assuming the HHS interpretation becomes DEA’s standard, going forward, a drug can have a “currently accepted medical use” if there is clinical experience using the drug with at least one medical condition in a substantial number of jurisdictions.

High-Level Guidance Going Forward

The discussion above does not necessarily validate all aspects of the current state-level legalization approaches. But, conceptually, it validates a state-by-state approach to access with some medical component. And, it provides instruction or guidance on what these initiatives should improve or incorporate going forward. Below I’ll discuss four high-level points.

Facilitators. Are facilitators licensed health care professionals? In the medical marijuana scheme, recommendations came from mainstream, licensed healthcare professionals with years of training. In contrast, in Oregon, 18-year-olds can be facilitators. A state-level regime moving forward should find a way to incorporate medical professionals, keeping in mind that direct involvement may be impossible.

Data. Data is important toward establishing an accepted medical use. The HHS evaluation relied on data. Notably, that data largely did not consist of double-blind, FDA approved clinical trials. Thus, going forward, state-level initiatives should provide a means of collecting data. That doesn’t necessarily entail compulsory or coerced collection of data, of course, but it could be incentivized collection. How to carry that out is important, but beyond the scope of this essay.3

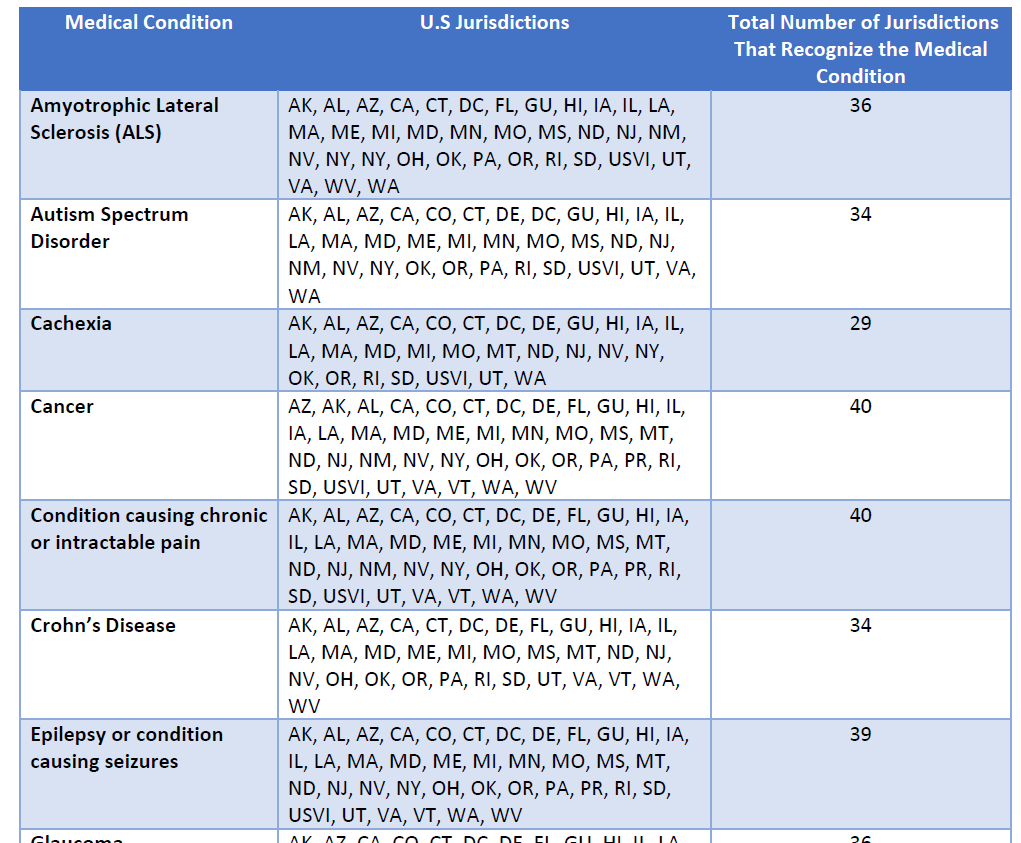

Conditions. A key feature of the HHS rescheduling decision turned on specific medical conditions:

Professional associations, infrastructure, and other non-profits supporting psychedelic assisted therapy. Again, look at the HHS report. Information provided by different non-profits and associations is up and down the document.

With tweaks to address the above concerns, the current state-by-state psilocybin approach could result in rescheduling of natural psilocybin products on a shorter and more successful timeline than it took marijuana.

Lastly, it is legally incorrect to assert that absent FDA approval, a Schedule III drug could not be used in medicinal practice. Check out my essay I wrote two years ago regarding intrastate use.

It is, of course, very rare that a contemporary food, drug, or cosmetic product has no nexus to interstate commerce because of the modern economy where product ingredients are sourced from different localities. But cannabis, plants, and fungi aren’t like these products insofar as every aspect of the operation—from seed or spore to sale—can feasibly occur in the same locality, even at some scale. And therefore, with some intentionality, it might be possible to design schemes or enterprises that operate outside FDA’s orbit. A product (i) whose ingredients are all sourced intrastate, (ii) is manufactured intrastate, and (iii) is transported and distributed solely to intrastate consumers, would be “purely intrastate.”

FDA’s jurisdiction doesn’t extend to purely intrastate operations, just as HIPAA may not extend to medical providers that don’t take insurance (gasp!), such as therapists.4

Conclusion—and Reflection

If one believes rescheduling is important to equitable and affordable access outside of an FDA-approved schema—and I do—then the above points provide high-level guidance. Further elaboration or legal analysis is warranted, but a task best saved for another day. Suffice to say, it is encouraging to see some of that red-tape oriented toward including explicit medical components, such as the recent draft DORA regulations in Colorado that distinguishes between “Facilitator” and “Clinical Facilitator,” the latter being for mental conditions.5

So, is it worth supporting these state-law initiatives? On balance, I think the answer is a qualified yes. To answer that question, let’s take a step back and put this in perspective.

The CAMU narrative above wasn’t a sideshow but important history. In the mid-1980s, MDMA became a Schedule I substance because it had “no currently accepted medical use.” That finding—based on the absence of FDA approval—sent Rick Doblin and his organization MAPS on a journey toward “net zero trauma” by thrusting MDMA into the FDA approval system. Doblin postulated that FDA approval was necessary to obtain rescheduling of MDMA—even if, in reality, it will likely result only in the rescheduling of Lykos’s proprietary product.

To get there, MAPS relied on philanthropic dollars to fuel a development process that lasted 30+ years. And in the end, the project became a pharmaceutical company. Far from reinventing the wheel, what MAPS accomplished was conventional. Rather than address the systemic issue that led to the scheduling of MDMA, MAPS leaned into an FDA-primacy model and current infrastructures for delivering medicine. What struggles FDA-approved MDMA assisted therapy faces today has to do with trying to fit a square peg (MDMA assisted-therapy) in a round hole (current system for approving and delivering medicine).

To be crystal clear, the approval of pharmaceutical MDMA will be a paradigm-shifting success worthy of celebrating. I absolutely support it. It is an incredible accomplishment. At the same time, it is important to call a spade a spade and recognize what kind of success will be achieved. No, it won’t be a reinvention of mental health care. No wheels will be broken. Rather, MDMA assisted therapy will be a novel drug with a novel delivery mechanism largely delivered through the current health care system. Adjustments. That’s all.

Compare this to the state-by-state movement, which could accomplish what took MAPS 30+ years in a fraction of the time. I’ve lamented state-level medical/recreational marijuana initiatives, but let’s be clear: those initiatives has made marijuana very accessible to far more people far faster than MDMA will. And, unlike the MAPS approach, the new approach is a paradigm busting endeavor.

Months ago, at PS2023, I scoffed at the notion that state-level ballot initiatives had a greater return on (philanthropic investment) when compared to the FDA-approval path.

But looking back, the point is probably right.6 It depends how you define success. But if one sees the current federal administrative drug state as a partial cause of the mental health crisis as I do, the ROI for the state-level approach could be orders of magnitude higher in terms of innovation, speed, and under the right circumstances, access.7

In the meantime, for those in Austin, see you soon.

In principle, I do not and never have opposed state level initiatives, but do believe that in many respects, they are not being done right or with a proper appreciation of the legal frameworks at issue.

Indeed, rescheduling psilocybin under these terms would be far cleaner because, unlike marijuana, natural psilocybin isn’t covered by any treaty.

No, I’m not flip-flopping. I’m against compulsory collection of data.

“If an entity does not meet the definition of a covered entity or business associate, it does not have to comply with the HIPAA Rules.” A provider is a covered entity only “if they transmit any information in an electronic form in connection with a transaction for which HHS has adopted a standard.”

I basically agree with Mason Marks’s comments here about the questionable assertion that state programs “shouldn’t worry about the federal government” because cannabis successfully dealt with a federal/state conflict. The issues are completely different. Indeed, the assertion that physicians are involved in the distribution of medical marijuana misstates the holding of Conant v. Walters. I read the case to say the opposite. At the same time, I understand the general point: the federal government doesn’t prioritize active interference with those acting in accordance with state-level initiatives. That will probably remain true going forward. Also see note 6 re: regulatory entrepreneurship.

The point about group therapy and the myopic focus of individualized therapy in mental health is another good point. Still, the idea of rolling out psychedelics and figuring out implementation later—“move fast and break things”—is an approach best served for tech-apps, not psychedelic medicine and complex regulatory schemes. That said, whole articles are written on “regulatory entrepreneurship” or operating in gray areas until an industry becomes “too big to ban,” which is again why I’m not opposed to state-level legalization initiatives in concept.

Not to mention, the FDA approval path has clean access to capital markets, so allocating philanthropy to state-level initiatives while letting FDA-approval oriented operations rely on capital markets makes far more sense in terms of efficient capital allocations.

Do you support complete decriminalization with the appropriate healthcare policy around it or no?

That's the only question I need answered to lend you any credibility or not.