According to multiple outlets, late last month (originally reported by Smart Approaches for Marijuana) DEA sent a notice to Georgia pharmacies/DEA registrants informing them of the consequences of selling THC products that comply with state but not federal law.

As the notice indicates, this responds to the Georgia Board of Pharmacy’s decision to permit, under state law, independent pharmacies to dispense THC oils—oils that are Schedule I controlled substances and illegal under federal law.

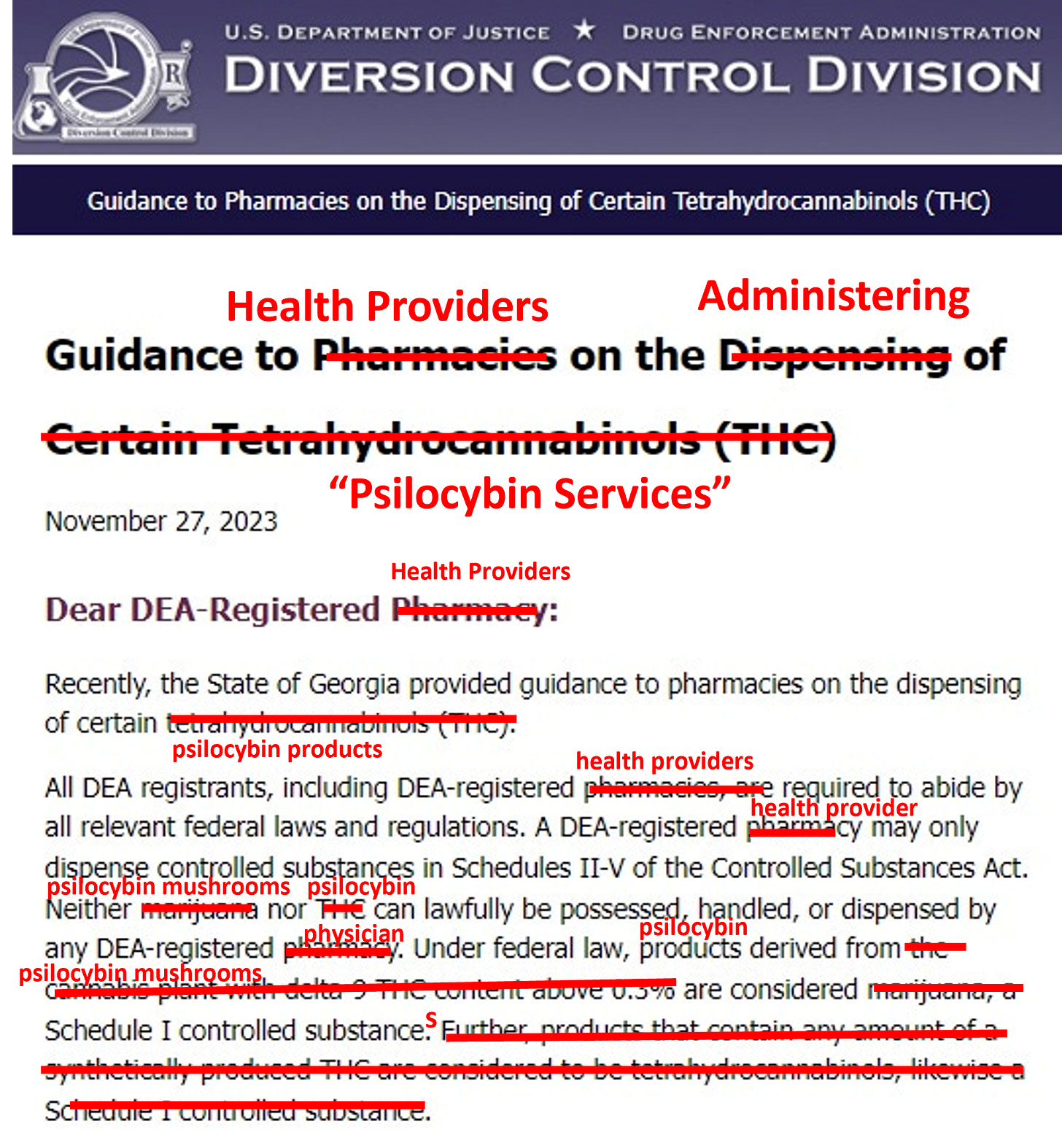

This notice should serve as a reminder when discussing these state regimes. They aren’t federally legal. Yes, it matters. Ignoring the federal CSA is simply not an option for some, for example, those not willing to put prescriber licenses at risk. Indeed, the above notice can be rewritten to cover any Schedule I substance or registrant:

Mason Marks argues in a recent JAMA piece that “[s]tate regulations can conflict with federal drug laws up to a point.” He contends, “state psychedelic programs are blurring the lines between psychedelics and health care services, far more than their marijuana programs do” and that “[p]sychedelic businesses and regulators in Oregon, Colorado, and states pursuing similar laws should be concerned.”

Certainly, as to the first assertion, it is hard to see how he’s wrong. As I’ve stated here and elsewhere (podcast, e.g.), the medical marijuana model fundamentally differs from the prevailing and increasingly medical “psilocybin services” model. In state medical marijuana programs, a doctor—perhaps a DEA registrant—makes a recommendation, which is then fulfilled by a non-registrant DEA dispensary. Under Conant v. Walters, this balkanized set-up protects licenses. The prevailing psilocybin model, in contrast, transforms services providers into pseudo-healthcare providers and practitioners.

While personnel supporting the creation and implementation of state-regulated psychedelics programs have been imported from the cannabis-industrial-complex, acting as if the state psilocybin programs can or should proceed in a manner just like to cannabis is foolish—at least from a law perspective. Certainly, some concepts translate, like 280E. But just wait until I have time to regale you about racketeering laws and why state regulated psychedelics models if (when?) legal synthetic psilocybin becomes approved raise RICO issues that play out differently than it does cannabis.

Whether any federal crackdown will occur, only time will tell. And what form enforcement may take is unknown. For example, FDA/FTC may not have the resources or jurisdiction to intervene, as Marks floats.1 Or, like cannabis, the federal government may noy enforce through prosecution or enforcement actions. Instead, it may be indirect enforcement through taxes and snatching back licenses. One paragraph from Marks’s article, with which I agree and is disturbing, deserves a special call out:

Some Colorado board members have even suggested clinicians could provide psychotherapy alongside psilocybin products and bill Medicaid only for psychotherapy by using existing billing codes. But billing Medicaid for those services under therapy codes and intentionally omitting the use of psychedelics could potentially violate the federal False Claims Act or constitute health care fraud, which is a crime.

Bottom line: if you are a medical professional flirting with these new systems, be careful. Certainly, dial down blasé echoing from the purveyors of the medical marijuana establishment. Get a robust and unbiased legal opinion. Don’t let someone shoot from the hip.

Finally, in my biased opinion, all this is why the attitude reflected in Governor Newsom’s veto statement is misguided. He stated, “California should immediately begin work to set up regulated treatment guidelines - replete with dosing information, therapeutic guidelines, rules to prevent against exploitation during guided treatments, and medical clearance of no underlying psychoses.” Let’s flesh this out his call to medicalize and bureaucratize unapproved psilocybin.

If, as a state, you want to do a psychedelics wellness program notwithstanding federal law, fine. No arguments here. Or, a recommendation oriented structure per Conant v. Walters that isn’t healthcare at the distribution/consumption level—that’s fine too. But the essential assumption underlying both schemes is that regulated psilocybin access is not medicine. If it is going to be medicine or delivered as “treatment” in a medical model, then it should involve medical professionals. But, as noted above, if those medical professionals have DEA licenses, those licenses are put at-risk. And that leaves prospective patients who may have serious “mental illness” unable to obtain medical treatment from qualified doctors as your system’s lodestar.

Many proponents of the bureaucratized psilocybin programs trumpet the mental health crisis as a reason to push forward a highly-regulated pseudo-medical model that promote treatments without FDA approval. Yet, the reality behind this talking point is that under these regimes, those with more serious mental issues might be unable to get this therapy from qualified medical professionals unwilling to put licenses at risk. Hence, why focusing on concurrent federal reform now is crucial.

Generally, FDA only has jurisdiction over interstate commerce.