Do you have the time, to listen to me whine?

Today’s lengthy essay is about taxes. Specifically, two items: 280E and 501(c)(3). (Go get your Adderall.)

The main thesis here is simple. The tax laws do not just penalize drug dealers. They are a primary and structural source of inequity, and any state legal/federally illegal system built on top of these provisions will be inherently and incurably inequitable. So, any good faith attempt to build equitable access to psychedelics must attempt to address the federal issues. They cannot simply be ignored or papered over.

But first, a disclaimer: I am not a tax attorney.

A Brief 280E History

Let’s start with IRS Code Section 280E, which reads:

No deduction or credit shall be allowed for any amount paid or incurred during the taxable year in carrying on any trade or business if such trade or business (or the activities which comprise such trade or business) consists of trafficking in controlled substances (within the meaning of schedule I and II of the Controlled Substances Act) which is prohibited by Federal law or the law of any State in which such trade or business is conducted.

Americans and American businesses pay taxes on income. This includes income from illegal enterprises, which invites the question: Should drug dealers be able to deduct business expenses? Congress didn’t think so—unless they’re dealing drugs listed in schedules III, IV, or V.

Before 280E, courts relied on common law doctrines to deny deductions to drug trafficking activities. Take the case Wood v. United States, 863 F.2d 417, 418 (5th Cir. 1989). Wood received $600,000 in marijuana commissions in the late 70s. He pleaded guilty to marijuana offenses, served four years, and paid a $30,000 fine. In 1985, the IRS discovered that Wood hadn’t paid taxes. Wood argued for a “loss deduction” under 26 U.S.C. § 165. The court denied the deduction, however, relying on a “sharply defined national policy against the possession and sale of marijuana.” “Allowing a loss deduction,” it explained, would certainly “take the sting” out of a penalty intended to deter drug dealing.

But then, in Edmondson v. Commissioner, the tax court ruled that a taxpayer illegally trading in stimulants and marijuana could deduct “ordinary and necessary” business expenses such as rent. So, in 1982, Congress stepped in. It enacted 280E to undo the Edmondson rule. The legislative history states:

There is a sharply defined public policy against drug dealing. To allow drug dealers the benefit of business expense deduction at the same time that the U.S. and its citizens are losing billions of dollars per year to such persons is not compelled by the fact that such deductions are allowed to other, legal, enterprises. Such deductions must be disallowed on public policy grounds.

On stage at PS2023, I declared the marijuana legalize-and-regulate movement to be a “failure.” I subsequently added some nuance. After all, it isn’t accurate to say that nothing good has come from the legalize-and-regulate movement or that it has been a complete failure in all respects. Incarceration rates, for example, have declined.

Nonetheless, the regulated access model has not achieved many of its purported goals. Equity, for example, is hard to see. And these regimes have left behind a regulatory wasteland. Many of the “achievements” are overstated. For example, the reduced stigma attributed to legalization can be just as much attributed to medicalization and demographic shifts as opposed to legalization itself.1 Even the incarceration-reduction data is open to qualification. According to data from the Office of Justice Programs report “Measuring the Criminal Justice System Impacts of Marijuana Legalization and Decriminalization Using State Data,” enforcement of marijuana laws in Washington and Oregon, for example, fell dramatically before legalization.

Or, consider this LA Times article that showed pot smuggling arrests in California climbing by 166% post-legalization. Huh? Illegal markets are still thriving.

A primary reason for the failure of legalized cannabis is 280E.2 280E is a key reason why I stated that state-level regulated legalization, largely through ballot initiatives, has moved and continues to move way too far out in front of federal reform.3 (Read endnote 3 about same-sex marriage. Seriously. It’s important.)

Move fast, break things—sort out the mess later.

Or in the case of 280E, the strategy is mostly don’t figure it out at all. As stated by this Inc. article in 2016:

While the marijuana industry has accomplished a lot by reforming state laws, the road to profitability and sustainability is still far away and requires changing federal law, which has been resilient to the legalization movement.

We are in no materially better position today.

So, What Does 280E Do?

By its terms, 280E forbids income tax deductions or credits for businesses that “consist[ ] of trafficking in schedule I or II controlled substances.” What is “trafficking”?

The starting point lawyers and accountants turn to is Californians Helping to Alleviate Medical Problems (CHAMP), Inc., 128 T.C. 173 (2007). In that case, the tax court defined “trafficking” to mean “to engage in commercial activity: regular buying or selling of marijuana.” The tax court then held that 280E doesn’t “deny the deduction of all of a taxpayer’s business expenses simply because the taxpayer was involved in trafficking in a controlled substance.” It concluded that the “supplying of medical marijuana to its members” was “trafficking,” but also held that under that case’s facts, providing caregiving services separate from providing medical marijuana was not “trafficking.” According to CHAMP, under certain choice circumstances, it is possible to run a state-legal/federally illegal controlled substances enterprise.

The taxpayers in the Vapor Room case didn’t fare as well:

Each of Vapor Room’s staff members is permitted under California law to receive and consume medical marijuana. Petitioner purchases, for cash, the Vapor Room's inventory from licensed medical marijuana suppliers. Patrons who visit the Vapor Room can buy marijuana and use the vaporizers at no charge, or they can use the vaporizers (again, at no charge) with marijuana that they bought elsewhere. Sometimes, staff members or patrons sample Vapor Room inventory for free. When staff members interact with customers, occasionally one-on-one, they discuss illnesses; provide counseling on various personal, legal, or political matters related to medical marijuana; and educate patrons on how to use the vaporizers and consume medical marijuana responsibly. All these services are provided to patrons at no charge.

….

§ 280E precludes Petitioner from deducting, pursuant to I.R.C. § 162(a), the ordinary and necessary business expenses associated with his operation of the Vapor Room. We therefore affirm the Tax Court's decision.

Now do Harborside:

Harborside's sale of items that didn't contain marijuana--such as branded clothing, hemp bags, books about marijuana, and marijuana paraphernalia such as rolling papers, pipes, and lighters--generated the remaining 0.5% of its revenue.

…

And the record shows no separate entity, management, books, or capital for the nonmarijuana sales. This leads us to find that the sale of non-marijuana-containing products had a “close and inseparable organizational and economic relationship” with, and was “incident to,” Harborside's primary business of selling marijuana.

…

The relationship between Harborside's marijuana business and holistic services closely fits Olive's “Bookstore A” analogy. Just as a bookstore that gives away coffee is still only a bookstore, a marijuana dispensary that gives away services is still only a marijuana dispensary.

…and so it went for just about every other litigant to stare down 280E in court. The reality is that CHAMP is an outlier.

The takeaway is that section 280E doesn’t cover all controlled substance related activities. Can one segregate business activities? Maybe. But gee golly, doing so is not straightforward. It is not easy. And if the tax man comes calling—which may take a few years—buckle up buttercup.

Yes, The IRS Takes 280E Seriously.

Audit rates in the state-legal-federally-illegal marijuana industry are high. There is a reason for this.

Two years ago, MJBizDaily published an archive of FOIA documents related to the IRS’s enforcement of 280E with marijuana. According to the article:

They show the IRS found it was a more productive use of agents’ time and resources to audit marijuana businesses than other mainstream industries after the agency calculated that marijuana companies owed more in unpaid taxes than their federally legal counterparts.

In these documents, we see the IRS’s “Compliance Initiative Projects.”

And we see helpful slides on how IRS sees the law:

These IRS presentations courtesy of MJBizDaily provide great insight, not just for cannabis companies, but for the emerging psilocybin industry. And today, the IRS has a page devoted to 280E.

280E and the Marijuana Industry

Because of 280E, marijuana companies can face tax liabilities of up to 80% of their income.4 Crushed under the weight of 280E, little wonder few companies in the cannabis plant-touching industry turn robust profits. Many are circling the drain.

As Harris Bricken attorney Griffen Thorne states, the taxes associated with the state-regulated market have allowed the illegal market to proliferate:

Is it any wonder why the illegal market is doing so well while established cannabis businesses are falling by the wayside and going into insolvency? If the federal government truly cared about the cannabis market – a market that employs hundreds of thousands of Americans – it could solve this problem in five minutes. Even states have the power to cut out the shenanigans and take the pressure off the industry.

Cannabis taxes are too damn high. And until the problem is solved, don’t be surprised when the industry falls to pieces.

Economists Robin Goldstein and Daniel Sumner say state-level cannabis legalization “hasn’t lived up to the hype.”5 “On the business side, companies have shut down, farms have failed, workers have lost their jobs, and consumers face high prices.” Sounds like equity to me. Their book Can Legal Weed Win? is “packed with unexpected insights about how cannabis markets can thrive, how regulators get the laws right or wrong, and what might happen to legal and illegal markets going forward.”

Also, marijuana related businesses cannot seek bankruptcy protection, which may also factor into why marijuana companies face interest rates on business loans multiples of what legal businesses pay.

Not surprisingly, marijuana businesses have attempted to develop tax strategies to mitigate 280E’s impact. There is no need to discuss them in detail. Suffice to say, 280E optimization strategies operate like all tax optimization strategies do: manipulating corporate forms and cost allocation to ease tax burdens. This can be achieved, for example, by siloing different business activities and controlling the supply chain. Or, vertical integration, which allows increased cost control along the supply chain and, therefore, can help maximize tax deductions by increasing COGS for goods sold at retail while allowing more cost deduction by capitalizing them into inventory.

Of course, the result is bizarre business structures that require significant capital to pull off and maintain. Vince Sliwoski at Harris Bricken posts a real picture of one such operation before concluding that these operations “seldom work[ ]”:

Vince’s sober assessment of this:6

I trot out this particular example because the architect was an experienced CPA. The CPA got a lawyer to stand behind it and one key investor to invest (for all the nonsense you see above, there were really just four or five “people” involved in this apparatus). We represented the investor as the apparatus failed spectacularly over a period of years, spawning multiple litigations and threatened litigations. The lesson? Even credentialed professionals may promote these rats’ nests.

Next problem. The professionals in the marijuana adjacent services industry that help you set up or maintain a tax mitigation strategy—few of whom shoulder 280E burdens themselves—don’t work for free. Not only do these folks not work for free, they make money off of these complications. Indeed, but-for 280E type complications, many of these folks wouldn’t have much work.

In short, assisting businesses cope with 280E and other consequences of the state/federal divergence is its own cottage industrial complex—one that directly benefits those professionals (and perhaps only those professionals).7

Looking Forward: Oregon, Colorado, Etc.

That brings us to Oregon, Colorado, and as of last week, Massachusetts. In many ways, these regulated access systems differ from cannabis. For example, the services center differs from the dispensary. It isn’t clear why.8

For a variety of reasons, I suspect 280E will result in more pain and inequity in the emerging psilocybin services industry than experienced in cannabis. Not only do some expect 30% higher prices, but the price of psilocybin services will be higher, making the lack of insurance coverage far more acute. To be clear, we should’ve learned lessons from 280E and cannabis. But rather than question the new approach, we’re leaning into it, and the only solution I’ve heard appears to be better tax-avoidance planning on the front end.

That’s all well-and-good, but let’s not fool ourselves: this is inherently inequitable.

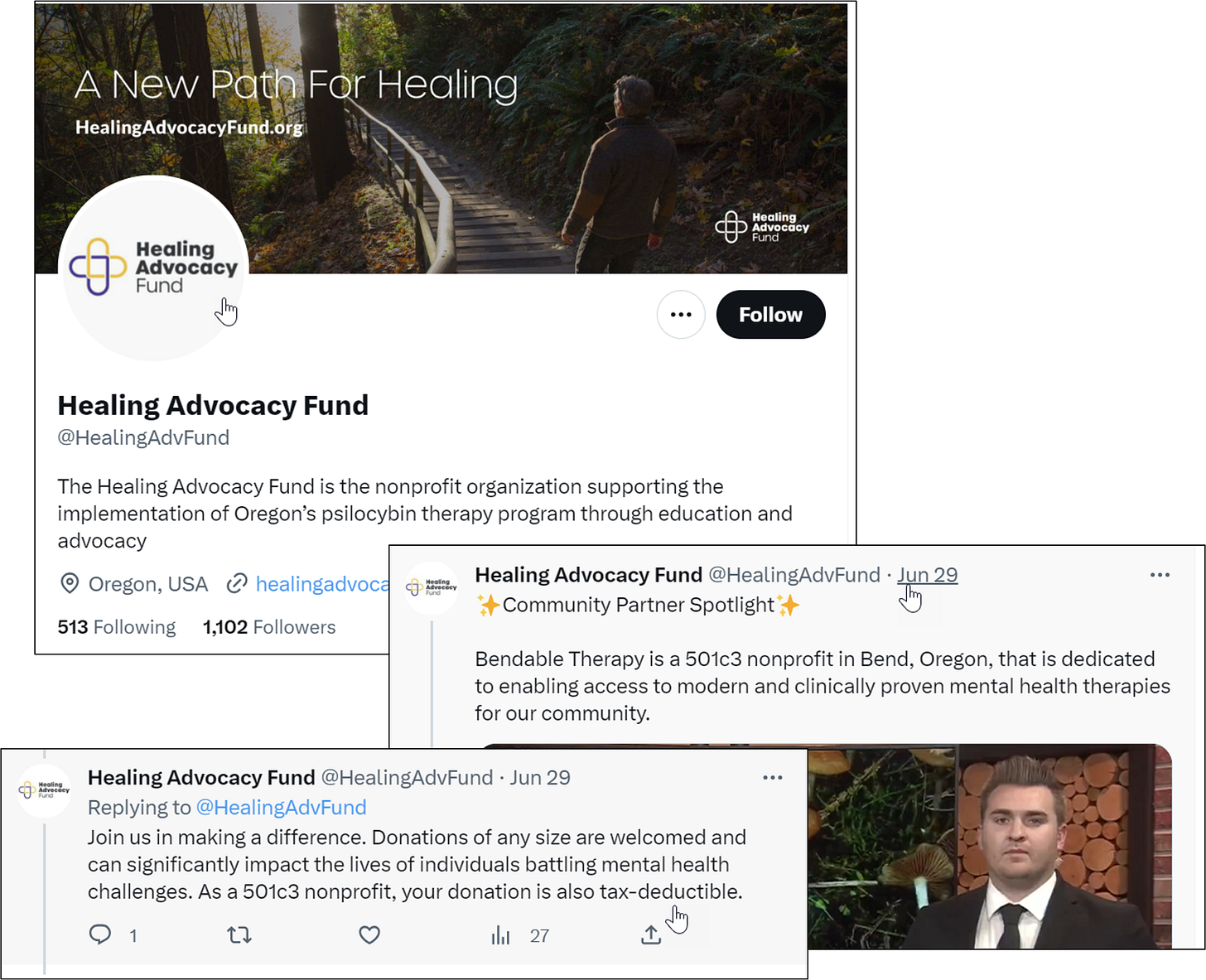

To that point and their credit, the Healing Advocacy Fund—a 501c3 non-profit that “works to implement safe, high quality, and equitable psychedelic therapy”—provides an “Oregon Psilocybin Industry Toolkit” to help you overcome these burdens. Under “Know Before You Start: Major Considerations,” there is a “Service Center Toolkit” that flags 280E. In bold type, we see Recommendation: Hire a Lawyer and Certified Public Accountant, illustrating my point precisely:

Your lawyers and CPA should be familiar with either cannabis or businesses dealing with Schedule 1 substances and tax code 280E and should communicate and work together to provide you options for your business structure.

We understand the cost to hire a lawyer and CPA is significant, but we believe it’s imperative to enlist experts to advise on how to set up your business particularly because it’s a new industry that works with a Schedule 1 controlled substance that remains illegal under federal law. They will also help you understand your legal and financial risk and have a clearer sense of what it will take to be a viable business.

Typically, start-ups do not hire General Counsels until $5 mm to $10 mm of revenue. Lawyers are cost centers. But in psilocybin services, you need a lawyer from Day Zero just to plan your business. That’s an incredible cost center from the get-go. And, whereas accountants and lawyers usually perform services based on precedent and reliable guideposts, here, you’ll be spending money on a bet.

There is no guarantee that your customized 280E plan will succeed. See above about the IRS catching on to marijuana-ops a few years after the fact.

For all you know, this is a house of cards. There is no way they—or anyone—can even project any degree of confidence that what they are building will work. And you won’t find out for three to four years, at which point you’ll hold the bag while that lawyer and accountant you hired will be onto some other project in some other state market building a new legal contraption—which again, may not work either. But of course, they won’t be working under the weight of 280E, because 280E only hits the folks actually participating in the market for controlled substances, not those that create the market or service it.9

Because of all this, I’ve been trying to have more conversations about the viability of the scheme. I’m not opposed to state-level legalization. The current FDA and health care system is crap and built on several fundamental epistemological fallacies. We should have wellness programs that can operate at the intrastate level without federal regulation and interference. But at the same time, I believe in building robust systems—not castles on swamps.

I always bring up 280E. My skepticism is met in a variety of ways. In one conversation, it was conceded that maybe these convoluted 280E tax avoidance structures would not hold up. But I was assured that the IRS wouldn’t catch-on for five years after which the Oregon program would be up and running and many people would be helped.

Maybe so. Probably right. As discussed above, it can take the tax man a few years to catch-on and catch-up. And the people who will pay the price aren’t the folks setting up the scheme and working in the services industry. It will be the participants and users of the scheme.10

Let’s form a Non-Profit!

Okay. Taxes are the problem. So, why not form an entity doesn’t have to pay taxes? Since we’re building crazy structures to dodge taxes, why stop at convoluted shell entities. Why not dream bigger?

After all, if the goal of regulated state access is to provide healing and equitable psychedelic access—and if we no longer give a shit about FDA approval, don’t need any VC money, and don’t need any patents—why not do the whole drill without any profit motive?

Bendable Therapy appears to be trying to do that. It purports to be a “a 501c3 nonprofit dedicated to enabling access to modern and clinically proven mental health therapies for our community” including “legal psychedelics.”11 Because of its non-profit structure, Bendable Therapy12 appears to provide some of the most affordable “psilocybin services” in Oregon at $2,300 a pop. For 12 hours of facilitation, that’s not unreasonable.

Healing Advocacy Fund, a 501c3 non-profit itself, promotes Bendable Therapy:

Here’s the catch. (There always is one.) This is a magnificent house of cards.

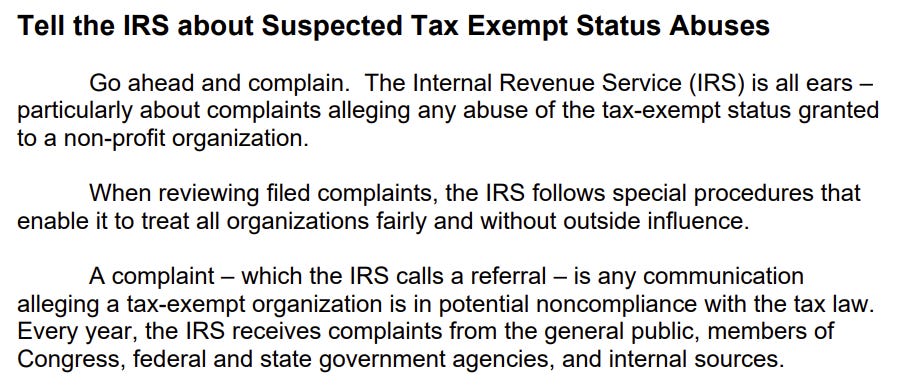

The IRS usually doesn’t allow 501c3s to use funds for non-exempt purposes. That includes promoting illegal activities under the CSA, as these non-profits unquestionably do. Below, for example, is Form 13909:

Can you really argue that these non-profits are not using income/assets “to support” federally illegal activities?13

So, take an organization formed to:

promote the medical and mental health benefits of Entheogens, psychedelic plants including Psilocybin, Peyote, Ayahuasca and Ibogaine; fund research into novel uses of these plants; and persuade the public to support re-scheduling cannabis and the entheogens out of Federal Schedule One so they can be more easily studied and used by physicians and the public.

Is this a non-profit? According to an IRS private letter determination (PLR 202217009), no:

You are seeking to fund research with controlled substances. Federal law does not recognize any health benefits of Dimethyltryptamine, Ibogaine, Marijuana, Peyote, or Psilocybin and classifies them as Schedule I controlled substances. 21 U.S.C. Sections 802(16) and 812. You have provided no authority to show that it is legal for any person, institution or company to use any of the substances that are the subject of the research you seek to promote and finance. It is your burden to show that using these controlled substances are permissible. An organization cannot be granted exempt status if its operations promote illegal activities. Furthermore, federal law prohibits the manufacture, distribution, possession, or dispensing of a controlled substance. 21 U.S.C. Section 841(a). Congress has “made a determination that marijuana has no medical benefits worthy of an exception” to the general rule that the manufacture and distribution of cannabis is illegal.

Read the letter very carefully. A lot of it is boilerplate that applies across the board. A case it cites, Mysteryboy, is instructive. In Mysterboy, the IRS refused to grant an exemption to an organization that, in typo ridden submissions, described itself and its purpose as:

working for law change to protect the rights of sexual active consenting kids and adults; and to amend child sexual photography law; to provide counseling to sexual active kids adults; and scientific studys; educational, artistic

…

To executive scientific study and research into the pros and cons of decriminalizing natural consensual sexual behaviors between adults and underagers and decriminalizing what is defined as child pornography. Such research and studies will consist from secondary anaalysis a research method in which a researcher uses data collected by others, also research and study will be recorded from oral visitation and observation of consenting participants, ALSO such studies and research will include trips of travel world-wide and will be executed by myself or by paid part-time employees or by volunteers. Such study and research will also look into the relationship of forced abstinence and why it produces hateraid and violense in a majority of cases. Such findings or conclusive facts will be converted into an educational material form and will be distributed to the general public and legislatures for tconsideration for use in law reforming/repeals/ decriminalization/or for use in making new law bills.

Secondary programs will promoot safe sex; promoot friendship/peace and love undiscriminally world-wide…

I know what you may be thinking: child porn and consensual relationships between kids and adults is completely unlike the consensual use of psilocybin and plant medicine. Urging the decriminalization of, collecting data on, distributing educational material related to, and promoting safe sex in consensual relationships between sexually “active consenting kids and adults” is fundamentally different from decriminalizing, collecting data, distributing educational material related to, and promoting safe use in consenting adults using psilocybin. But from the law’s viewpoint, they are not so different. Both are federally illegal.

So, the following legal recitals in Mysterboy are relevant:

“The presence of a single substantial purpose that is not described in section 501(c)(3) precludes exemption from tax under section 501(a) regardless of the number or the importance of the purposes that are present and that are described in section 501(c)(3).”

“If an organization is engaged in a single activity directed at achieving various purposes, some of which are described in section 501(c)(3) and some of which are not described in that section, the organization will fail the operational test where the purpose not described in that section is more than insubstantial.”

“Both Federal and State laws exist for the purpose of prohibiting the sexual exploitation and other abuse of children. … The above-quoted purpose of petitioner in its articles of incorporation would, as those articles acknowledge, require activities by petitioner to effect changes in existing Federal and State laws.”

“An organization organized and operating to influence legislation does not meet either the organizational or operational test for exemption under section 501(c)(3). In addition, the reforming/repealing and decriminalizing laws meant to protect children from sexual child abuse and sexual predators is contrary to public policy and would encourage illegal activity. Therefore, your organization would not be exempt under either IRC 501(c)(3) or (4).”

A medical marijuana mutual benefit corporation organized exclusively for public and charitable purposes “to provide disadvantaged adults suffering with cancer, anorexia, AIDS, chronic pain, spasticity, glaucoma, arthritis, migraine headaches, or any other illness for which marijuana provides relief who comes to your facility or uses your delivery services to feel cared for, valued, safe and respected.” Nope. “Nationwide religious organization” consisting of people who share a similar religious doctrine or spiritual and scientific perspective that the use of “Sacraments.” No. What about a group that provides “financial assistance to patients using medical marijuana by paying for a one-month supply.” Nada.

Bottom line: the 501c3 as a means to implement these models could turn out to be more vaporware. Consider yourself warned.

Soul Tribes

Next up on the tax-exempt tour is the “Soul Tribes Bond.”14 Brace yourself for this one.

“Did you know that over 300 million people worldwide experience depression? … At Soul Tribe International we recognize the challenges that individuals with trauma, depression, anxiety, PTSD, ADHD, face in their daily lives. ”

And from the June 2023 press release:

What will the bonds be used for? A 60,000 square foot facility. That’s bigger than a football field.

“Strategic initiatives,” eh? More on that in a moment. The Soul Tribes Bond is associated with Soul Tribes International Ministries located in Detroit, Michigan.

Folks, I’m really speechless. +10 points to the Soul Tribe House for creativity. -10,000 on the legal. We’re not even trying anymore.

In my not-so-humble-not-a-tax-lawyer-legal-opinion: you can’t start a church, parade around language like treating mental illness, openly advertise a “sacrament” to treat DSM acronyms, discuss “walk-ins,” openly solicit investment in your church in the form of bonds to build a 60,000 square foot facility, create a “dispensary,” and build an “infrastructure for housing” for veterans—and claim a non-profit exemption as a church organized exclusively for religious purposes.

The supposed basis for the tax exemption here appears to be RFRA—the Religious Freedom for Restoration Act:

I’ve written about RFRA before. Many other folks have too, such as Chacruna’s RFRA guide.

In the UDV case, the Supreme Court held that the CSA could not be enforced without exception to bar the UDV Church’s use of ayahuasca in religious ceremonies. It did not hold, however, that a church has an inherent right under RFRA to use ayahuasca without regard to the CSA. Rather, it held that DEA had to accommodate sincere religious practice.

Following the case, in 2009, DEA put forward guidance on how to seek religious exemptions. A lot can be said about these and the need for actual rules, as we’ll see in the next section.15 What is germane for this section is that UDV does not stand for the proposition that a church’s use of ayahuasca or any other controlled substance is legal without strings attached. The Supreme Court merely held that, under RFRA, DEA could not categorically deny adherents from using sacramental substances with no exceptions.

In the case of the Soul Tribe church, I doubt they have a DEA exemption. So, that’s problem #1.

Problem #2: Is it a church? The legal analysis on whether the church needs to register with the IRS to be exempt may be sound in the abstract. A 508(c)(1)(A) qualifying group—“churches, their integrated auxiliaries, and conventions or associations of churches”—is different from a 501(c)(3) insofar as a “church” does not need to register to qualify for 501(c)(3) status. As stated in IRS Publication 557:

Where the rubber hits the road is the next point: whether a group registers with the IRS or not, it still needs to be a church and meet all the same 501(c)(3) criteria. “[S]ection 508(c)(1) simply relieves churches from applying for a favorable determination letter regarding their exempt status as required by section 508(a). Nothing in section 508(c)(1) relieves a church from having to meet the requirements of section 501(c)(3).” Taylor v. Comm'r, 79 T.C.M. (CCH) 1364 (T.C. 2000)

Also, a religious organization can be tax-exempt but not a church. But unlike a “church,” a religious organization must be blessed by the IRS to get the benefit of a tax exemption. In the Foundation of Human Understanding case, for example, the group described itself as “based upon Judeo–Christian beliefs and the doctrine and teachings of its founder, Roy Masters,” Based on a “church-tax inquiry,” the IRS concluded that while the Foundation was entitled to retain its tax-exempt status under section 501(c)(3) as a “religious organization,” it was not a church based on the IRS's 14 criteria. The trial court applied the “associational test” instead: “To qualify as a church an organization must serve an associational role in accomplishing its religious purpose.” In other words, a church must bring people together and have “regular congregations” or “regular religious services.”

The requirement that a church be “organized and operated exclusively for religious or charitable purposes” remains. Is a church that openly advertises use of “plant medicine” to medically treat mental illness operated exclusively for religious purposes…? What about all the other stuff? Just because the IRS hasn’t issued an adverse determination against Soul Tribes (yet) doesn’t mean it is in the clear. Not even close. “Such a transparent sham will not stand even the most cursory analysis.” Universal Life Church, Inc. v. Comm'r of Internal Revenue, 83 T.C. 292, 301 (1984).

I mean, is this debatable?

What kind of church has “investors”? What kind of church estimates “daily walk-ins” at 300-500 with an “average donation of $100”? What kind of Detroit church (let alone a non-profit) pays its CEO $350,000, almost 6 times the localized median income, and has “mycologist sales” on the payroll? How about $350,000 in expenditures for “direct mail campaigns”? Campaigns for what?

The church said, in a press release, its primary purpose was “the use of psychedelic therapy and spiritual healing to address the nation’s mental health crisis.” Notably, in listing its purposes, “religious freedom” isn’t even first. It’s last.16

Next slide, please.

Iowaska Church of Healing

The Iowaska Church of Healing is embroiled in a dispute playing out right now in the D.C. Circuit in what I consider to be one of the most important legal cases going on in psychedelics.

The Iowaska Church of Healing is a non-profit organization whose members' sincerely-held religious belief involves the consumption of ayahuasca, “a tea brewed from South American plants that contains a drug illegal under federal law.” That’s undisputed. The Church is not a pop-up fly-by-night ayahusaca operation.

The officers and directors of the Church get paid $0. It will provide the opportunity for other services, including services to veterans.

The Church did mostly everything right. In January 2019, it applied for a 501(c)(3) exemption and was candid in its papers. Shortly after, it applied for what it called the “necessary religious exemption from DEA.”

What happened? Oh, you know. The IRS said no.

So, Iowaska sued.

The trial court held that Iowaska was not organized for tax-compliant purposes because its “substantial purpose remains in violation of federal law.” As mentioned above, Iowaska was organized to promote healing through its religious use of ayahuasca. Additionally, the court held that Iowaska was not operated properly either because, “absent a CSA exemption,” Iowaska’s activities amount to the “illegal distribution and promotion of the use of a controlled substance, a non-exempt purpose.” Read that phrase again. And again.

Here’s the rub. The Church applied to get an exemption from DEA. It couldn’t get one in a timely fashion. DEA has been sitting on the application. The e-mails are in the administrative record:

Setting aside some of the deep substantive flaws with DEA’s guidance, it would be one thing if the IRS required groups to obtain religious exemptions from DEA and DEA turned around a decision in 90 days. But DEA is not doing that, and that is a real legal problem for sincere churches that genuinely want to obtain religious exemptions from DEA to operate with confidence that their religious activities are protected.17

The case is now on appeal. The underlying issues in Iowaska case are tremendously important. If the law does not allow Iowaska to hold a non-profit exemption as a church for use of ayahuasca in religious settings, then the fidelity of the 501c3 exemptions held by many other psychedelic organizations ought to be called into question.

New Crazy Idea: Put Indigenous Back in Medicine?

So, 501c3 doesn’t look like a robust fix—or at least not without some litigation. But since we’re on the topic of tax workarounds, maybe another type tax-exempt vehicle can help us:

Federally recognized tribal governments aren’t subject to income tax—even for commercial activities. The indigenous can set the terms of their engagement. They can dictate their own affairs. They don’t need state-run token, lip-service, and aspirational committees on reciprocity and how to use their own medicines. Nor would they need assistance from the cottage 280E support services industry or “investment bonds” … wait, this may explain everything! Nobody except the tribes makes money off this operation.

I could go on, but I’ll leave it to the readership to figure out the details.18 Admittedly, my idea isn’t even half-baked. Surely, some creative mind can figure this one out.

Before I conclude, I need to tap Shane in for a bit. My hands are cramping, and I need to retrieve my mind, which I lost somewhere around endnote 17. Brb.

+ Commentary From the Exhausted Editor (Shane)

So, Matt disappeared for a while about a week ago. He wasn’t answering his phone or returning emails. I started to worry.

Then today, out of the blue, he called me saying he needed my help with an On Drugs post. I said “sure” but demanded to know where he’d been. “Writing the post,” he said. With great trepidation, I asked what could have required six days of isolation. “I’m writing a labyrinthian screed about 280E, 501(c)(3), and a psychedelic church selling tax-exempt bonds. Oh, and I’m doing it in the style of Infinite Jest.”

As I began slogging through his draft (no, I haven’t read the whole thing and let’s be real—no one is getting through this whole thing), two things occurred to me. First, Matt is a basket case. Second, he titled the post “Death and Taxes” but never talks about death.

Now, I assume Matt has some brilliant, abstruse reason for leaving death out of it. My guess is that, in his own way, Matt is signaling that he understands that this neurotic to the bone tome on taxes will likely be the death of On Drugs itself. Or maybe Matt spoke of death in terms of the cannabis industry.

In any case, since I have the attention of the two (maybe?) of you still reading, I thought I may as well explain another way that death is in play here.

Unlike taxes—280E specifically—which Matt correctly recognizes will remain a guarantor of inequity in the psychedelic space until we address systemic problems with federal law that continue to bog down popular “reform” efforts, death is the Great Equalizer. The tax man may only affect those with skin in the game, but death comes for us all—eventually. And in America right now, it’s coming for far too many amidst a mental health crisis, an overdose epidemic, and record-breaking suicide rates. These are problems that no CPA or clever tax attorney can scheme around, and importantly, we all have skin in this game.

To me, this is what makes psychedelic policy reform compelling and urgent: It offers a promising answer to some of the worst plagues facing America today. To be clear, I’m not saying psychedelics themselves are some sort of panacea that will solve the mental health crisis or end veteran suicide. I don’t have the scientific expertise necessary to evaluate such claims. My personal suspicion is that many of the of them will eventually prove overblown—at least to some extent.

Rather, I’m bullish on psychedelics for a very different reason:

I know that the systemic dysfunctions in federal law that have prevented us from unlocking their potential (whatever it may eventually prove to be) have facilitated and exacerbated the deadly mental-health crises we’re facing right now. Thus, while expanding access on its own may not save us, solving the systemic problems necessary to do so very well could.

In short, Matt is right. The only thing I have to add is that while addressing the deeper issues necessary to reform federal law may be hard, doing so really is a matter of life and death, too.

Conclusion

Conversations about the merits of state-level regulated or religious access initiatives and equity/access concerns ought to begin with federal tax law.

If equity/access concerns you—and I’m not saying it necessarily should—seek answers to these questions. How will a regulated system address the inequities caused by 280E? Carefully listen, and don’t settle for broad, vague, ambiguous, overly ambitious statements, or Rube Goldberg fixes that may not work and where the cost to setup and maintain is significant. Moreover, we should think about regulated access on multiple axes. The state model is just one. The religious/spiritual path, done right, is another potentially (perhaps more) viable path to open up access. Done wrong, and it drags everyone down.

At bottom, some believe building castles on a swamp and watching them slowly sink is better than doing nothing. I might see this as a productive first step if, at the same time, like civil rights movements, we focused efforts on draining that swamp.1920

As of today, I don’t see that happening. Instead, I just see folks building more and more elaborate castles or churches on top of the swamp, praying the next one won’t sink.

Am I just paranoid? Or am I just stoned?

Public polling had more than 50% of Americans favoring legalization in 2011. About 60% of younger demographics have always favored legalizing. Most of the folks opposed to legalization in 2011 were in the 65+ and older crowd—the crowd that raised children through the Reagan years, the pinnacle of the War on Drugs.

It is possible if not likely that the majority of the shift in public sentiment has been opposition aging out; generational shifts have prompted a change in attitudes, facilitating legalization at the ballot box, not the other way around.

Hence, a reason why federal reform remains hard. Ballot box demographics do not reflect the demographics of legislators and agency officials, and do not necessarily change their minds. Congress, for example, is a gerontocracy run by septua- and octogenarians. Although I have no empirical evidence to show this, I’d bet there is a stronger correlation between age and how federal legislators feel about drug policy reform versus any other metric, including political party—hence why Matt Gaetz, among other rock hard conservatives, favors rolling back the drug war.

Moreover, as Seema pointed out at our PS2023 talk, drug policy issues can be popular but not salient. The difference between issue popularity and issue salience is critically important. By their nature, ballot measures capture the popularity—but not the importance—of an issue. Eking out a majority is different from convincing the public that an issue is worthy and important. In addition, salience can be asymmetrical. Those opposed to something can be very opposed (and obstruct) while those in favor can be only mildly in favor, and thus, in favor of a measure in the abstract but unwilling to work for that issue in the face of opposition.

I should also distinguish between recreational legalization and medical access. I believe the medical movement has been, on balance, a success. The distinction arises in the differing goals between a medical vs. recreational program. Medical marijuana, for starters, probably contributed to reduced stigma more than recreational legalization. And obviously, a decriminalization initiative (as opposed to regulated access legalization) reduces criminalization directly.

Comparing the current state level legalization movement to the same-sex marriage movement is inapt. For example, David Bronner here writes:

Ending the drug war and integrating psychedelic healing into American culture is a national cause and issue, and like the gay marriage movement, we need to fight state by state until we achieve full national victory. Ballot measures need a good team of in-state and national supporters, as they are complex and costly but can drive huge policy shifts.

The ultimate success of the marriage equality wasn’t “state by state.” Quite the opposite.

Congress passed the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in 1996 in reaction to a Hawaii state case called Baehr v. Miike—an example of legislation following litigation, albeit in the opposite direction. At the same time, the Supreme Court decided Romer v. Evans. In Romer, the Court concluded that a Colorado state constitutional amendment precluding protected status based on homosexuality or bisexuality violated the Equal Protection clause.

From there, our journey toward equality passes through Lawrence v. Texas, where the Court struck down sodomy laws based on the notion that “[l]iberty presumes an autonomy of self that includes freedom of thought, belief, expression, and certain intimate conduct.” Importantly, Lawrence and Romer established a slightly heightened standard of review (i.e., more protection) called “rational basis with bite” for traditionally disadvantaged groups, including LGBTQ, laying the foundation for the path to victory in United States v. Windsor in 2012.

When we look at the political landscape, until 2007, voters overwhelmingly approved—including through ballot measures—same-sex marriage bans. Until 2007, same-sex marriage was prohibited in nearly every state except Massachusetts. And the courts played an indispensable role.

In 2008, former New York Governor David Patterson ordered state agencies to recognize same-sex marriages performed in other jurisdictions. The IRS then saddled Edie Windsor (who had married in Canada) with $363,053 in federal estate taxes because the IRS didn’t recognize her same sex marriage under DOMA. Former Paul, Weiss (my former firm too) litigator Robbie Kaplan saddled up, sued the federal government in late 2010 on behalf of Windsor, took the case to the Supreme Court, and won in a 5-4 decision in Windsor.

Importantly, Windsor was handed down in 2013 at a point in time when 10 states recognized same-sex marriage—generally not by ballot initiatives:

2003: Massachusetts (courts)

2008: Connecticut (courts), California (courts—undone by Prop 8)

2009: Iowa (courts), New Hampshire (legislation), Vermont (legislation), DC (legislation)

2011: Hawaii (legislation), New York (legislation)

2012: Maine (ballot), Maryland (ballot), and Washington (ballot)

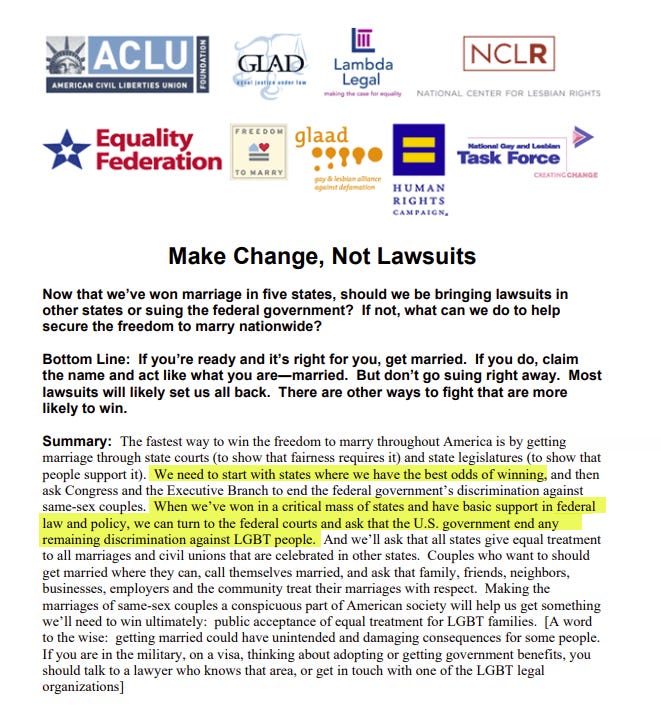

And looking at the U.S. as a whole, national polling showed slightly more support for same-sex marriage (48%) than against (43%)—not unlike where marijuana was in 2011. As Kaplan explains in her book, mainstream LGBTQ rights organizations counseled against lawsuits in 2009:

However, if the major gay rights organizations had had their way, we never would have filed Edie’s lawsuit in the first place. On May 23, 2009, three weeks after I met Edie, the powerhouse legal team of David Boies and Theodore Olson filed a federal lawsuit in California seeking to overturn Proposition 8, the ballot proposition and state constitutional amendment that outlawed marriage between people of the same sex in that state. Passed by voters in the November 2008 election, Prop 8 was obviously a terrible setback. If we could not win a referendum on marriage equality in California, what hope did we have of winning in less progressive states. Yet although Prop 8’s passage was an appalling disappointment, this new lawsuit felt to many like a silver lining. Having Ted Olson—a staunch Republican, former solicitor general and lawyer for George W. Bush in the dispute 2000 presidential election—take on the cause of marriage equality appeared to be a huge step forward for the cause.

Once the Prop 8 suit was filed, however, the major gay rights organization were not at all happy about it and tried to stop anyone else from trying anything similar. On May 27, 2009, a seven-page release went out, cosigned by GLAAD, Lambda, HRC, the ACLU, and others, urging people to “make change, not lawsuits.” The press release offered this as the “bottom line”: “If you’re ready and it’s right for you, get married. But don’t go suing right away. Most lawsuits will likely set us all back. There are other ways to fight that are more likely to win.”

Here is the full flyer:

In particular, consider the following passage from the ACLU strategy flyer:

There are two things we need to do to win the freedom to marry nationwide. First, we need to change the law. Like other civil rights movements, we are doing that state by state, starting with the states where we have the best shot. In some states, we’ll get marriage through the state legislature, to emphasize that it has popular support. In other states, we’ll go to the courts, to highlight that excluding same-sex couples is inconsistent with basic principles of fair play.

When we’ve been successful in the states most likely to go our way, it will be easier to win in other states. As we build significant support among the states, we’ll be able to ask Congress and the Obama Administration to give our marriages the same treatment the federal government gives all other marriages, by including them in federal laws and programs. Congress could do that in a single bill. The Administration also could increase LGBT equality through countless federal regulations and Executive Branch policies.

A few years earlier, the ACLU Director of the Lesbian & Gay Rights Project published a similar warning in an essay entitled “Don’t Just Sue the Bastards! A Strategic Approach to Marriage.” See also “Winning Marriage: What to Do,” the 2005 ACLU playbook on achieving “marriage for same-sex couples nationwide in 15 to 25 years.” According to the playbook, this could be achieved with “a stable of professional consultants, in addition to the current staff of national and state organizations, who know the issue, know the research, and who can be deployed to help local and state organizations with education, lobbying, organizing and mobilizing allies, and designing and mounting ballot campaigns.”

Turns out, this was horseshit. One federal lawsuit—Windsor—cleared the logjam and broke the floodgates across the nation and put some projects in the same-sex equality non-profit industrial complex on the backburner: “After the Windsor decision, litigation challenging the constitutionality of state-based bans on same-sex marriage exploded, some brought by the national LGBT legal groups, but many more by private attorneys.” That lawsuit didn’t require tens of millions of philanthropic dollars or donated capital for decades of going state-by-state winning “significant support.” It just required a damn good gut-wrenching fact pattern; top-notch, premier advocacy; and a potent federalism argument in an amicus brief tailored to win Justice Kennedy’s support. (Note that the ACLU and NYCLU co-counseled the Windsor case with Paul, Weiss.) And afterward, members of the non-profit complex “decided to be nimble, change [ ] litigation funding position, and funnel a significant amount of money for the first time in its history into the litigation strategy.”

In fact, it’s hard to overstate how wrong the ACLU strategy could have been. The Supreme Court has only drifted right/conservative since Windsor. Had the movement waited 5-10 years for more states to get on line, marriage equality in the Supreme Court would likely have lost 5-4 or 6-3 with Justice Kennedy’s retirement.

Following Windsor, the opposition to same-sex marriage crumbled. Left and right, federal courts began striking down same-sex marriage bans (and other discriminatory practices) as unconstitutional relying on Windsor. This deluge of federal court litigation striking down gay marriage bans occurred at a time when a minority of states recognized same-sex marriage. Let me quote Robbie Kaplan again:

In civil rights litigation, there’s an ongoing debate about the best strategy. Political organizing? Grassroots protest? Media work? Or do you bring court cases? If there’s a lesson to be learned from Windsor, it’s that the answer is “all of the above.”

And then, of course, in 2015 came Obergefell, which elevated same-sex marriage to a fundamental right. Restrictions on same-sex adoption—gone. And in Bostock, conservative-textualist-libertarian Neil Gorsuch, John Roberts, and four of their colleagues ruled that Title VII extended to protect LGBTQ rights based on a textualist reading of a federal statute that makes it “unlawful ... for an employer to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

Now, I’m not saying one should compare same-sex marriage to drug-policy initiatives. There are so many basic differences between the two that maybe the approaches should and must be different. For example, there is a world of difference between passing ballot initiatives to create regulatory access regimes so that people can access mind-altering substances (independent of religious beliefs) and core fundamental rights like human sexuality and marriage. And there are differences in how one puts those types of issues to voters. Ordinary people do not typically have the background to fully understand the legal and regulatory consequences so as to make an informed decision. Oregon 109, for example, is a relatively long text. When most voters enter polling places, many do not know much, if anything at all, about the ballot measures they will be asked to vote on. Same-sex marriage, on the other hand, is easy to get.

But if we are going to make this comparison, let’s be honest. There are only superficial similarities between the current advocacy strategy sponsored by millions of dollars pouring into state-by-state drug legalization and the strategy that resulted in the success same-sex equality movement. If even a fraction of that money were poured into strategic legal defense campaigns to protect and expand rights through the courts—as was the case with the same-sex equality movement and every other successful civil rights movement—as a matter of justice, we’d make progress faster and achieve more equitable outcomes. To repeat, contrary to the talking point above, same-sex equality and rights were predominantly achieved through the courts. Doubling and tripling down on state-legal initiatives without removing the legal obstacles that create inequity merely doubles and triples down on inequity.

Put simply, I am not necessarily saying one should not support state level initiatives to open up equitable access. The FDA model sucks. As with the same-sex equality movement, these initiatives in some form have an important role. But naked state ballot initiatives without actively engaging federal law in Congress and the courts won’t get us anywhere toward a better system. If the marriage equality movement truly is the playbook for achieving drug policy reform—and again, I’m not saying it should be—query whether resources should be split more proportionally between these initiatives and strategic litigation, like every other successful civil rights movement. A successful strategy ought to be “all of the above.”

As a point of comparison, the corporate tax rate is 21%. And, in the past, if a company used a double Irish with a Dutch sandwich or what not, it could get that down even further to close to zero:

I worked with Goldstein on the litigation I brought against Texas for banning smokable hemp products. Brilliant guy. He studies cannabis markets, with a focus on the effects of regulations and retail prices—precisely the type of economist and person I would consult before and during the establishment of these state-regulated markets and associated regulations. Goldstein has “an A.B. in Neuroscience and Philosophy from Harvard, a J.D. from Yale Law School, and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Bordeaux.” “[F]or the past six years, Dr. Goldstein has been advising the California Bureau of Cannabis Control on the economic impacts of cannabis regulations and other economic issues.” In other words, Goldstein isn’t a hype man. He’s the expert you call when you really want to understand the issues surrounding whether a state legal system is economically viable.

We took the smokable hemp case all the way to the Texas Supreme Court. Although we lost our constitutional claim, we overturned the ban on selling smokable hemp products. That court decision, in turn, has Sid Miller, Texas’s Republican Agriculture Commissioner, asking the legislature to fix the issue.

Why do I listen to Vince and his colleagues at Harris Bricken? Because, as he states in this article, his firm has been “setting up psilocybin companies for clients,” which “is meat-and-potatoes work for [them], as [they’ve] formed hundreds of schedule I substances businesses in Oregon over the years.” Their interest thus appears to be to perpetuate the system. When someone who has a vested financial interest in seeing a scheme move forward instead issues caution, I believe that caution is credible, should be heeded, and given extra weight.

The structural effects created by 280E is one reason why I find it increasingly difficult defend rescheduling criticisms doled out by those in the social justice, populist, and equity wings of the cannabis collective. Take the following suggestion offered by Parabola Center’s “Anti-Monopoly” Toolkit:

This may be a good idea. But of course, alcohol didn’t labor under the weight of a tax provision that incentivizes if not requires some level of vertical integration to survive a fatal tax blow. Until one solves the 280E issue, the language above would either (a) throw more marijuana businesses further into 280E tax hell or (b) incentivize even more convoluted business structures. Section 280E only applies to Schedule I and II. So, marijuana rescheduling to III would remove financial constraints that preclude serious consideration of proposals like the above. It would also allow more serious consideration of equity proposals—which are the first to go when the going gets tough. And it would free up cash to pay better worker benefits and wages, which under 280E, may not be deductible.

So, advocates like Weldon Angelos deserve praise for bringing attention to important criminal justice issues. As I stated above, I agree that, by and large, state legalization has not delivered enough on promises or in proper proportions to populations most impacted by the War on Drugs. But to say rescheduling falls “woefully short of the meaningful reform” is deeply mistaken.

Because of 280E, rescheduling to III is a massive equity issue. Period. One could argue it is too little too late. Fair enough. Unlike the situation of 5 to 10 years ago, the cannabis industry is essentially already formed and many companies are swirling the drain. Had rescheduling been done in 2016, for example—and yes, amid the rec legalization craze there was a legal path to do it—maybe the case would be different. Again, rescheduling would not legalize a recreational market. What it would do, however, is drain one of the main rotten underpinnings of the economic inequities that do occur.

Also, this general observation isn’t just about 280E. Rather, it is about the justice system at large. A system or rules that increase barriers to entry, make access to capital unreasonable, and necessitate the hiring of an army of service professionals, exacerbate disparities between haves and have-nots. This is precisely why creating a system rooted in opacity and building workarounds will be inherently inequitable.

See endnote 9, second paragraph.

This is a core problem with these initiatives and many others: skin in the game. Per Nicholas Taleb, skin in the game is a problem that arises when “an actor pockets some rewards from a policy they enact or support without accepting any of the risks.” Because of this problem, “it is hard to tell if macroeconomists, behavioral economists, psychologists, political ‘scientists’ and commentators, and think-tank policymakers are experts. Bureaucrato-academics tend to be judged by other bureaucrats and academics, not by the selection pressure of reality.”

According to the skin-in-the-game principle, having shared risk when making decisions is essential for fairness, efficiency, and risk management. Have you ever noticed how the proponents of these convoluted state-level regimes don’t bear any of the risks of their failure, and even worse, some actually benefit from the legal complications? There is a notion, for example, that states can’t just decriminalize psilocybin and allow it to be sold over-the-counter with warnings because that would be unsafe. So, instead, we need to establish a complicated set of training programs, etc. and control/regulate all aspects of the model. Query who benefits from all that? I’d be interested in seeing evidence about the social and individual risk difference between THC/psilocybin that would justify a dispensary model for the former but not the latter. High doses of THC may present the same dangers as other hallucinogenic/dissociative substances. Scientifically, I see no reason to regulate the two differently.

A key idea here is the Intellectual, Yet Idiot (IYI) actor Taleb describes. Taleb describes these folks as a “class of paternalistic semi-intellectual experts with some Ivy league, Oxford-Cambridge, or similar label-driven education who are telling the rest of us 1) what to do, 2) what to eat, 3) how to speak, 4) how to think… and 5) who to vote for.” These “academico-bureaucrats who feel entitled to run our lives aren’t even rigorous, whether in medical statistics or policymaking.” According to Taleb, “the IYI believes in one Ivy League degree one-vote, with some equivalence for foreign elite schools and PhDs as these are needed in the club” and “speaks of ‘equality of races’ and ‘economic equality’ but never went out drinking with a minority cab driver (again, no real skin in the game as the concept is foreign to the IYI).” This paragraph seems particularly apt:

Typically, the IYI get the first order logic right, but not second-order (or higher) effects making him totally incompetent in complex domains. In the comfort of his suburban home with 2-car garage, he advocated the “removal” of Gadhafi because he was “a dictator,” not realizing that removals have consequences (recall that he has no skin in the game and doesn’t pay for results).

The critical point is that proponents of these regulated regimes—what I will call the cannabis-legalization-industrial-complex—don’t bear any of the risk, unlike those who will participate in the scheme. The purveyors aren’t the ones who will be paying 280E taxes, for example. Thus, they “can cause monstrous iatrogenics without even feeling a shade of a guilt, because they are convinced that they mean well and that they can be thus justified to ignore the deep effect on reality.” And then they move on to the next state—or they make even more money servicing all of those that entered the industry.

You see where I am going with this: many proponents and supporters of these regimes are out-of-state IYIs with no skin-in-the-game. That doesn’t make them bad or evil people. But it does fuck with incentives and introduces negative risk into these systems that isn’t borne by the purveyors that might not otherwise be tolerated. If I told you to design a regulatory regime and that you would have to run a business under it, you would come up with something very different from the one you’d propose if you knew only others would be operating in it. By way of analogy, you wouldn’t hire folks from San Francisco or Colorado to write appropriate laws about street parking in Miami.

According to skin-in-the-game, the folks who should be writing these ballot measures and implementing them in the states are the future actors from that state who will be participating in the scheme and will bear the downside risk or their representatives—not intelligentsia outsiders or industry lawyers with no skin in the game.

See endnote 9.

Psilocybin is not a “legal psychedelic.” It is legal under state law, but not federal law.

Curiously, the exemption was initially registered in July 2022 under the name “The Stoop Foundation.”

See endnote 11.

The Soul Bonds Website has a pretty restrictive Terms of Use. I encourage you to check out its website directly. I’m using just enough material to make my point.

Moreover, the existence of these churches highlights the need for clear rules on how to obtain an exemption.

This is why we can’t have nice things. Of course, I support challenging the status quo. But unlike state-legal regulated access models, this operation does not even have the veneer of legitimacy in my eyes. Moreover, operations like these jeopardize the entire good faith religious access movement. Who do you think Kevin Sabet and the anti-drug lobby will point to next in their efforts? As, perhaps, they should. Little wonder the DEA hasn’t put out rules to govern RFRA exemptions.

If you dig into the church, it gets way worse. Check out the operational budget, for example, that puts 7% to food banks and expects $14 million in donations in year 2.

The operational budget also includes the following:

The Church advocates for the use of psychedelics and other controlled substances in general, and intends as part of the Use of Funds to provide service offerings that include the use and sale of psychedelics and other controlled substances. These substances are illegal. The Church interprets, and relies upon its interpretation of, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act to permit its use of such substances. If the Church is incorrect in this interpretation, if any applicable law changes, or if the Church is otherwise unable to lawfully distribute or permit the use of psychedelics or other controlled substances, this would substantially impair the value of the projects to be developed by the Use of Funds and render the Church unable to meet its obligations, including the obligations represented by the Use of Funds.

The Church’s interpretation of RFRA is most likely wrong.

It appears that Soul Tribes is affiliated with the “Oratory of Mystical Sacraments,” an:

all-encompassing religious organization that respects, values, and draws upon the ethical religious, mystical, and spiritual arts and wisdom of any and all of Earth’s peoples, developed or practiced at any point throughout mankind’s existence, and has a nationwide network of members successfully exercising their rights to religious freedom and the pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness, as they pertain to Sacraments.

This organization provides a “notarized OMS membership document that offers a more detailed description of legal rights and Sacraments, legal precedents from Supreme Court rulings, notification of Title 18, U.S.C., Section 241 & 242, and other vital information.” And it, too, relies on an unregistered IRS church exemption.

See endnote 17 on how to get DEA to timely rule on an exemption application.

One could think of less ambitious ways to mitigate some inequities caused by 280E. For example, one inequity is that certain operators in the ecosystem bear far more of the burden than others. This often economically incentivizes vertical integration, which as many point out, leads to other inequities. Instead, the state regulated access model could tax entities less affected by 280E (e.g., facilitator training) and redistribute tax revenue to others in the ecosystem to spread out the pain. Haven’t really thought this through though.

Excessive and excessively long footnotes and endnotes are obnoxious and annoy me. But they serve a literary purpose in this piece. They are designed to reflect the convoluted, labyrinthian, and fractured items it derides, the 280E tax workaround, the state regulatory clusterfucks, the “churches” being formed, etc.

Having trouble navigating? Precisely. Like ballot measures compared to implementing regulations, the essay’s endnotes have equal if not more substance than the main text. It is an entire second narrative. Hence, the DFW and Infinite Jest reference. Just as ordinary folks can’t be expected to make informed decisions about these complex issues based on ballot measures, as noted in the last sentence of the third-to-last paragraph in endnote 3, I don’t expect you to read or understand each of the endnotes.

So what do I believe? Easy to shit on other ideas and not propose one’s own, right?

First, I don’t think anyone has figured it out. Certainly, I don’t think folks who know almost nothing about the Controlled Substances Act and administrative law have it figured out. I find it incredible that so much philanthropic money backs ideas purveyed by folks who have no body of knowledge relevant to their pursuit.

Second, the church idea is loony, but is also not so substantively different from a regulated access non-profit. I support religious access and expanding the domain of what is considered religious. I do not support using RFRA as a vehicle to open up mental health clinics with $14,000,000 budgets and pay $300,000 salaries.

Third, we should figure out at least plausible answers to the challenging questions to state regulated access in the face of contrary federal law before passing these laws through ballot measures.

Fourth, I support the laboratories-of-democracy idea and trying regulated state access. I even support the implementation of models I disagree with and believe to be inferior or fundamentally flawed, so long as folks are warned of the risks.

But inherent to the merits of the laboratory idea is proceeding as one would do with an experiment. We need to see results and figure out how to get at least one state-regulated model to work in concert with federal law and/or parallel to the medical model before going hog wild on any approach. That means getting a few of these systems online with some diversity in the approaches and actively implementing the schemes and ironing out the conflicts, including in the courts.

So, no, one group unloading dozens of ballot initiatives at this point in time is not the right path. But at the same time, I can hardly endorse a mass roll out of the East Coast approach. I’m particularly jazzed about the Weiner bill and the attitudes underlying it: “Let’s stop arresting people for possessing and using … then we can build from there.” The CA legislation appears to adopt a more incremental approach to building a framework for therapeutic use.

We should have diversity. No model has proven to be successful. Nobody knows what will or can work or what is best for a certain community. Let the people of a particular jurisdiction who will have to live with the law lead and choose what they want.

That’s my current assessment. Nobody has proved their concept works. Nobody has figured out the glaring and fundamental issues between state/federal law. And the folks that will ultimately bear the risk should be the ones leading in designing the initiatives for their communities. No scientist worth their salt would subject patients to Phase 3 trials of a treatment before completing a Phase 2 let alone a Phase 1. So why should a regulated access model that may not deliver on its promises and we know, from the get go, has deep fundamental issues that may or may not be able to be sorted out be spread? In an effort to maintain an open mind, I’ve been speaking to core proponents of these state-regulated access models. Not a single person has provided me a coherent, cogent answer to this basic question. Empty platitudes don’t count.

Certainly, I see urgency to deliver therapies, even experimental ones, to dying patients and others who are desperately in need. I believe that anyone should be able to try any safe treatment (even ineffective ones) with informed consent. The iatrogenic risk/reward in these cases is just different and not well addressed by the current FDA model. I volunteer inordinate hours of my time to that value.

But let’s be real and honest. That doesn’t justify these state regulated access regimes. MAPS should be getting approval for MDMA in 2024. COMPASS won’t be too far behind with psilocybin in 2027. Any state not named Colorado that is approving a ballot initiative in 2024 forward will not be able to deliver until 2027. So, the banal talking point “[w]e’re in a mental health crisis, and research has shown that psychedelic medicines can be effective in providing relief” is just that—a talking point. MAPS and COMPASS should have their products available by 2027, likely with some insurance coverage to boot. It is entirely possible that even off-label these treatments might be more affordable/accessible and $3000+ per pop.

Invoking the “mental health crisis” to justify state regulated access is also uncomfortable for me to read. While I don’t think anyone should be compelled or pressured to use any type of drugs—including by making false statements like “Everybody is Doing Drugs,” the indescribably crappy title of a new documentary produced by friend of On Drugs, Ronan Levy (see trailer)—I believe many can benefit from regulated and safe access to psychedelics, even those without any mental illness. Psychedelics can be used religiously, spiritually, and as part of a wellness routine—safely and productively.

Those urgently in need of these treatments, however, should have the option to get treatment by the most qualified professionals. Here, the state-regulated access models fails to deliver. Despite being branded as “regulated, licensed, supervised psychedelic therapy,” the most qualified practitioners for many urgent cases (i.e., psychiatrists with DEA licenses) will likely not participate because they don’t want to put their DEA licenses at risk. If the purpose is to provide a reasonable alternative address the mental health crisis, unless someone finds a way for doctors with DEA licenses to participate, this system likely fails at its essential purpose.

(Of course, the church-as-clinic model is orders of magnitude worse. And one could make a decent argument that, despite its deep flaws, state regulated access isn’t perfect, but a harm reduction tool. I actually buy that.)

Perhaps what we’re trying to do with these state legal models is establish a more decentralized and locally oriented model to medicines—plant medicines in particular—and diminish the power of the federal government and FDA to regulate healthcare and wellness. If so, I’m 100% on board. This is why I am not opposed, in principle, to Oregon 109s and so forth. Read this piece where I discuss several intrastate models “outside the ambit of FDA,” particularly the ending. The healthcare system is broken, and it has a lot to do with top-down centralized authority, the FDA safety/efficacy paradigm, and how it is ill-suited to mental health. The current federal bureaucratized system has a bad IYI problem.

But even in this vein, psychedelic access is only a beginning or catalyst to changing the mental health system. Without any concerted effort to affirmatively confront underlying structural issues—as other civil rights movements did and do—accruing philanthropic dollars and blindly rolling out state regulated access under a mantra of helping mental health and unloading a truckload of regulations and support staff to help prop up inherently broken system won’t get that done any more than shelling out dollars to a pharma company for SSRIs helps patch over PTSD symptoms and makes life livable but not worth living. Let’s take the analogy farther. Without affirmatively confronting the underlying structural issues, we’re dealing with the societal equivalent of a person that suffers childhood trauma, takes psychedelics, feels better and enlightened, thinks she is healed, but never did the hard work to confront and address the deeper issues that led to the pain—and instead goes around evangelizing and liberalizing psychedelics as a panacea and miracle cure, thinking psychedelics “healed” her. Did they? Or, are the problems as bad as before but transposed. Are we worse because now we’re proceeding under a pseudo-delusion that all is healed? Sometimes my mind plays tricks on me.

In sum, building a better and more equitable mental healthcare system is possible. Improving access to psychedelics can be an indispensable part of that narrative. But it requires considerably more than shotgunning psychedelics on any place where 51% of the populace might say “yes.” It certainly won’t happen by providing access just to “rich white men”. Psychedelics both on an individual level and societal level can only induce plasticity, i.e., the ability to cleanse the doors of perception, see unhealthy patterns, break them, and change. What one does from there is in fact what creates (or does not create) structural change. Dumping psychedelics on the masses therefore won’t change our broken mental healthcare and drug regulation system. It may even reinforce it. Real change requires a relentless effort to confront and fix the underlying structural issues with drug regulation. We should move fast and fix things.

Really great job, guys. You hit a crucial nail on the head (or really got the nail in the coffin?) by highlighting the importance of the "blanket no" language that allows a Simon-Cowell-style buzzer across the entire Sched I/II board. (File under: "Weightiest Copy+Paste Option Ever")

"Neat" ancillary fact: The IRS has also subpoenaed state seed-to-sale records to "mega-prove" audit determinations -- apparently the legal burden on the taxpayer to show that it was not in fact doing the exact thing it was doing was a bit too threatening. (But, in the meantime, it's good to know that the stuff that you're required to submit to the state for your activity to be lawful there also serves as a handy federal spare tire. FUN!)

This obviously took a lot, lot, lot of time to do, and thank you for doing it. Amazing job.

I'm one of those two still reading. That Iowaska Church is in the same town I live in, Des Moines, Iowa, so I've been following that case as has been the local media. As for Shane's comments, I look forward to hearing from Secretary Becerra on this topic. I enjoyed all of Matt's comments, so keep doing it!