On Downsizing

Gentlepersons, I’m back.

For the past few weeks of March, the Matt Zorn show has been on the road.

In early March I spent time in DC rubbing shoulders at the PMC event.

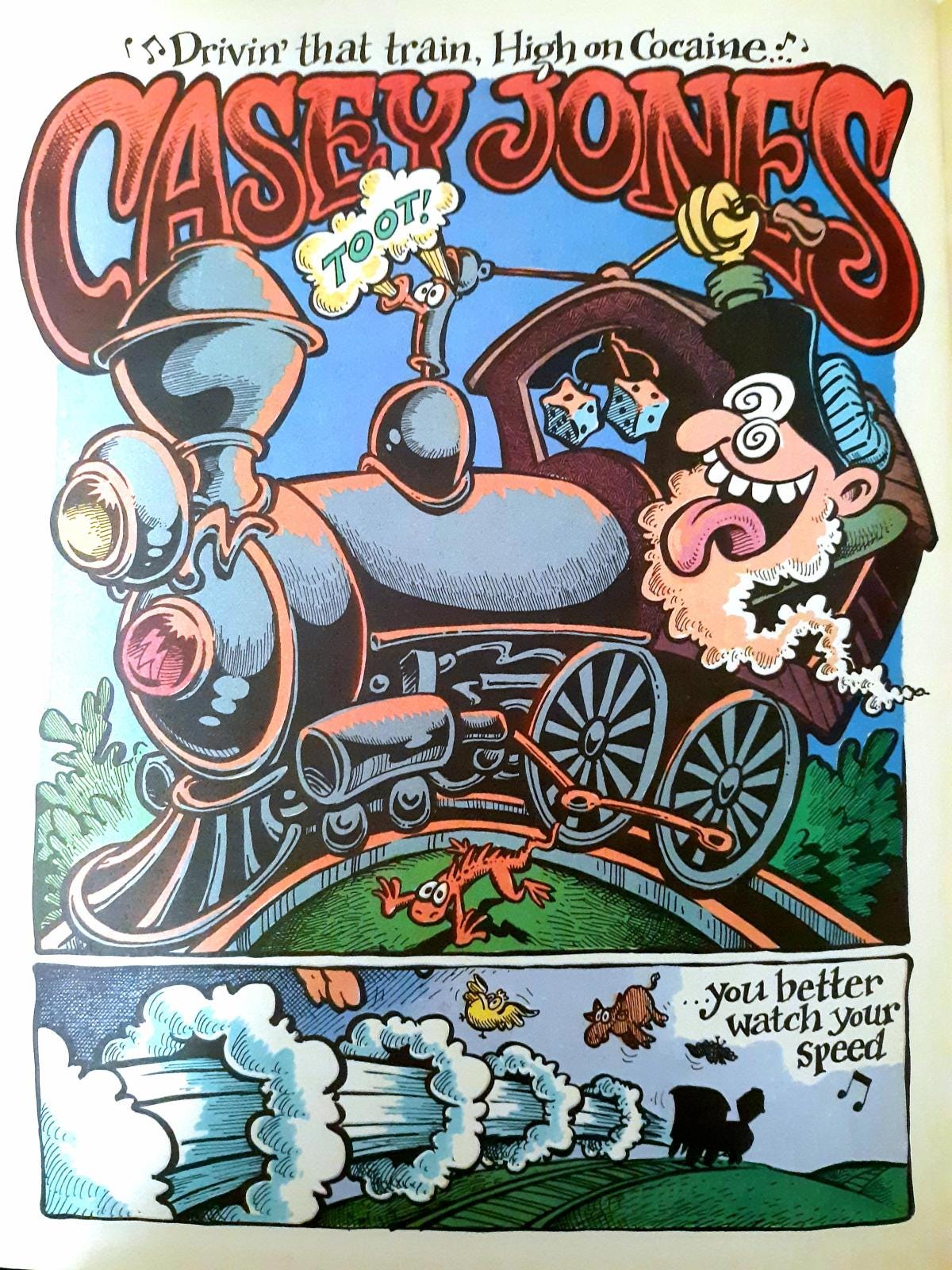

I then ventured out to SXSW in Austin and hopped on the psychedelic hype train where, adorned in my Luccheses, I riffed about dangerous drugs. Thanks to all that attended.

Three days later, I buttoned down and spoke my mind to a very different audience—one that included the Director of the Controlled Substances Staff (CSS) at FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). You know, the folks that provide expertise to FDA “as part of the review process in assessing drugs for abuse potential and dependence liability.” More on that below.

Somewhere in this chaos, I also recorded a second podcast with Hamilton Morris. In it, we discuss wide ranging topics, including patents, his Wonderland talk, and the reasons (or lack thereof) a select few were not allowed to attend Wonderland to hear his talk. Stay tuned.

But for now, my speaking tour is over. Time to earn back my stripes as psychedelic-keyboard-warrior-in-chief—even though I’m fairly sure the Psymposia crowd has the market cornered.

New content coming, I swear. For example, a piece on some patent gobbledygook argued Monday at the Supreme Court is imminent.

Field Gyp

One item I’ve long had in the works but is now iced is a pointed review on psychedelia’s most benevolent companies, Field Trip/Reunion Neuroscience.

Honestly, a Field Trip roast is hardly necessary. The parody writes itself. Take, for example, the following video. In it--through a thicket of hand-gestures and indecipherable corporate-speak garble--Field Trip’s former CEO, Ronan Levy tries to explain how providing psychedelic enlightenment to Rich White Men will improve equity and access for everyone. He fails, and in so doing, spouts off empty statement after statement that read like Onion headlines, such as Psychedelic CEO says "creating more inequity is going to create equity."1 You can't make this up. In a weird ironic way, this clip might be the Fountain of our psychedelic times. Today’s meditation: think about that.

Things continued to move quickly while writing my essay. Reunion filed a desperation lawsuit. You can see what I think in the Psychedelic Alpha article. Two weeks later, Levy mysteriously deleted all his tweets. (See the relevance of that immediately of below.) Days later, Field Trip collapsed and replaced Levy as CEO.

So my essay remains incomplete. But here’s a preview of what I had written:

This past January, I spent some time alone in a cabin in the woods to do some pondering about life. There, noshing on internet ordered psilocybin chewies, I did Yoga. For an hour, I stood perfectly still and held a tree pose—after which point I was convinced I was a tree...

Nah, just kidding. I did spend time alone in a cabin. But I sat on my ass half-naked drinking heroic amounts of diet-coke and coding a GPT-powered Twitter bot with my bare hands. After all, Field Trip was not going to save itself.

Looking at its income statements, I knew its chickens would come home to roost. Even heroic amounts of Mindset’s revolutionary patented compound couldn’t give it and its executives an original idea that could save the company. But maybe my new Twitter GPT Bot could help shave some fat off the “sales and marketing” line.

I call my creation RonanGPT.

Sadly, because my short, homemade script2 used Ronan’s past (now deleted) aphorisms to power GPT-generated new ones, like Field Trip itself, RonanGPT is now on hold. Still, good fun while it lasted. The AI generated tweet-aphorisms were as authentically inauthentic as those on the human feed.

Still, in the wake of Field Trip’s demise, I was going to comment on the rubble. Then, days ago, the consistently excellent Psychedelic Alpha preempted me. So it goes.

So now, I'm probably going to scrap the larger post-mortem. Unlike Reunion Neuroscience, I prefer to invest my time in novel ideas.3 My Field Trip/Reunion jokes appear to be winding down. One serious word, however.

I don’t view Field Trip’s collapse (and Reunion’s impending collapse) as a harbinger of disaster to come for every corporate psychedelics company, although certainly some of them. Many companies in the space have good leaders, products, and most important, good values. Like the dot-com bust, I believe survivors will emerge.

The case of Field Trip seems to largely be poor execution. The luxury, slick-design psychedelic clinic isn’t an intrinsically bad idea. Apple, for example, became the most valuable company in the world selling a slick-design, dressed up luxury version of BSD/Unix. But Field Trip aggressively over-expanded and never seems to have found a way to make a profit off its product. It never proved the concept, and then ran out of outside capital to burn through.

In my view, there is something deeper here too. Field Trip not only rapidly expanded in opening clinics, it also expanded by releasing podcasts, an app, and what not. To me, the company’s aspirations focused less on being a psychedelic clinic company and more on becoming a celebrity company with a cool psychedelic brand and a catchy name. Fair enough. With hard leg-work, a company can do well like that. Berner worked insanely hard and built a billion dollar empire with Cookies selling weed, after all. But if branding is your play, then your company better be authentic, have an exceptional individual at the helm, operate with laser focus, real and show work/substance underneath the brand. The company needs clear values that resonate with people and that people want to identify with. Apple, for example, has laser focus and core values.

It was never really clear to me what Field Trip stood for other than empty aphorisms and self-promotion. And who wants to identify with "Creating more inequity is going to create equity"?

The natural evolution of an emerging field always has a downsizing cycle. It will be good for psychedelics. Fewer in quantity often means better in quality. And in my book, quality always wins.

The Adderall Shortage

There’s another topic I’ve been wanting to publish on: a deep dive into amphetamine and the legal ins-and-outs of the Adderall shortage. Amphetamines very much shaped the current fabric of drug laws. Sadly, I’m waiting for DEA to return fruits on a FOIA request I filed months ago. Still waiting, even though DEA gave my FOIA request “expedited” treatment. *Sigh*

In the meantime, I strongly recommend this opinion piece in the Times by Maia Szalavitz about the Adderall shortage. It correctly notes that the origin of the Adderall is contested and some point fingers at manufacturing quotas imposed by DEA. Because amphetamine is a Schedule II drug, DEA must set an aggregate production quota (APQs) “to provide for the estimated medical, scientific, research, and industrial needs of the United States.” I’m not quite ready to embrace that conclusion for a few reasons.

But in any event, in my view, that isn’t the real takeaway of the opinion piece, which is:

[T]he regulation of medically used controlled substances should be transferred from the D.E.A., a law enforcement agency with no expertise in medicine, to the Food and Drug Administration, which specializes in health.

Szalavitz further explains that DEA responded to the opioid crisis by cracking down on doctors, “many of whom stopped or reduced prescribing, fearing legal consequences.” While prescriptions went down, opioid deaths continued to climb. From the AMA’s “2021 OVERDOSE EPIDEMIC REPORT”

These graphs might as well carry the caption “Failed Drug Policy.” As Svalvitz points out in an earlier essay:

[T]hat cutting the medical supply could potentially make matters worse didn’t seem to factor in to the calculations of those who supported this approach. But this outcome was, in fact, completely predictable— so much so that the phenomenon has an academic name, “the iron law of prohibition.”

Coined by activist Richard Cowan in 1986, the phrase refers to the effects of reducing drug supplies while not acting significantly to manage demand. Almost always, it results in the rise of a more harmful drug because of a simple physical fact: hiding smaller things is easier than hiding bigger ones. So, because illegal drugs need to be concealed, prohibition favors more potent and therefore more potentially deadly substances.

She goes on to make another deadly harm reduction observation—diverted pharmaceuticals are safer than street drugs:

[L]egitimate pharmaceuticals are required to be of a standard dosage and purity, which means that people know how much they are taking and whether it’s more or less than usual. Street drugs, by contrast, are unregulated. It’s difficult to be sure what’s in that mystery pill or powder, let alone what the appropriate dose should be.

COVID-19 didn’t cause the current synthetic fentanyl crisis. Perhaps the virus exacerbated the problem. But it certainly did not create it. Indeed, it doesn’t take a genius to figure out this one. But for good measure, let’s summon one:

DEA’s Origins

More than 50-years has been spent on a national law-enforcement, supply-side primacy drug policy experiment. It isn’t effective. The Adderall shortage is one symptom of a bigger structural problem. Others abound. The scheduling system—particularly Schedule I—is bonkers. So is the process for researchers, manufacturers, and practitioners to register with the DEA.

These issues all take root in structural decisions in the 1960s and early 1970s. It was then that the country decided to consolidate and put all drug control under the roof of a law enforcement agency filled with cops and treat drug issues as law enforcement problems first and foremost.

This is a historical detail Shane and I have extensively written about. And it is a detail I discussed during my portion of the SXSW panel with Rick Doblin, Sue Sisley, and Julia Mirer. Here’s the gist.

1.

Until 1951, no federal statute prohibited the distribution of dangerous drugs for other than medical purposes. The Durham-Humphrey Amendment to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) in 1951 added a requirement that any habit-forming or potentially harmful drug be dispensed under the supervision of a medical practitioner as a prescription drug and carry a warning: “Caution: Federal law prohibits dispensing without a prescription.” A violation would be deemed misbranding.

In the late 1950s into the 1960s, truck drivers began using stimulants—“bennies” or “co-pilots”—to stay awake while driving long hours. They got into accidents. And they tested positive for amphetamine or barbiturate use.

I hate to pre-empt myself here, but it is important to understand how the amphetamine epidemic into the 1960s is significantly responsible for today’s drug control regimes—and aspects of it shares a lot in common with other drug “epidemics,” including today’s opioid epidemic:

For decades, diet pill companies marketed their wares directly to doctors—and told them that by prescribing a rainbow of pills, they could sell the illusion of personalization. “You should have more than one color of every medication,” said one brochure, warning doctors never to prescribe the same combination twice. “That’s a little psychology and is well worth it.”

The rainbow was seductive, but it wasn’t necessarily safe. Amphetamine was combined with drugs like barbiturates. High doses and untested combinations were common. And though the medical establishment looked down on the fly-by-night clinics, the FDA was loath to regulate them because of the logistical challenge of taking down the thousands of clinics that dotted the United States by the 1960s.

Rainbow pills, for example, wasn’t about drug dealers getting kids hooked on speed. It was a marketing technique to help push diet pills by suggesting personalized attention and a treatment crafted to a patient's individual weight loss requirements. And of course, the famous 1968 exposé that captured the epidemic and helped convinced lawmakers that FDA couldn’t handle enforcement of drug laws.

2.

Enter the Prettyman Commission, a 1963 commission formed by President Johnson to recommend a program “to prevent the abuse of; narcotic and nonnarcotic drugs and to provide appropriate rehabilitation for habitual drug misusers.”

Up to 1965, drug legislation had been enacted against a backdrop of concern that the federal government had dubious authority to regulate aspects of drug control outside of the taxing and spending power. The Prettyman Commission explains:

When the Harrison Act [of 1914] was drafted, Congress was concerned about its constitutionality. The landmark cases establishing the full sweep of federal regulatory power under the commerce clause of the Constitution were yet to come.

Hence, the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, a law designed to combat reefer madness. The 1937 law placed a hefty tax on cannabis related activities but did not contain criminal penalties independent from the tax.

From the Tax Act to 1965, however, Supreme Court had been expanding federal authority to regulate commerce under the Interstate Commerce Clause. For example, in Wickard v. Filburn in 1942, for example, the Supreme Court held that Congress could regulate the production of wheat that had been manufactured and consumed purely intrastate, the reason being, the local manufacture and consumption of wheat would have a national effect upon interstate commerce in the aggregate. This quelled concerns about the federal government overstepping its authority by expanding into regulating the manufacture and distribution of drugs with criminal laws.

Free of the constitutional albatross, Congress enacted the Drug Abuse Control Amendments of 1965. This law plants many of the seeds that would later blossom into the Controlled Substances Act. Certain language and concepts from the Drug Abuse Control Amendments of 1965 get carried over into the CSA. For example, we see criminal sanctions for illicit activities. For the first time, federal law criminalized possession, albeit with sensible caveats to carve out personal use:

No person, other than a person described in subsection (a) or subsection (b)(2), shall possess any depressant or stimulant drug otherwise than (1) for the personal use of himself or of a member of his household, or (2) for administration to an animal owned by him or a member of his household. In any criminal prosecution for possession of a depressant or stimulant drug in violation of this subsection (which is made a prohibited act by section 301 (q) (3)), the United States shall have the burden of proof that the possession involved does not come within the exceptions (1) and (2) of the preceding sentence.

Consistent with the drug epidemic du jour, in signing the law, President Johnson placed special blame on stimulants and barbiturates, noting that “[u]nlike narcotics, some of these drugs are very easily and very cheaply manufactured.”4

The law also gave FDA new powers to enforce in Section 8 and resulted in the creation of the Bureau of Drug Abuse Control within FDA in February 1966 and its “D-Men” — the first federal agency whose mission was to combat drug abuse. But while the 1965 Amendments expanded federal authority into drug control and regulation, it still reflected an underlying philosophy of drug addiction as a public health problem. That would soon change.

The 1965 Amendments also contained another innovation. The law authorized the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare to investigate and control drugs having a “potential for abuse” because of a stimulant, depressant, or hallucinogenic effect. This is the precursor to today’s scheduling regime—and a huge step toward the modern administrative drug control state. For the first time, executive officials did not have to return to Congress if a new drug of abuse was discovered or became problematic. They could take action on their own.

3.

As discussed above, amphetamine and barbiturate use fueled the 1965 Amendments. In contrast, hallucinogen use precipitated the 1968 Amendments. Congress expressed deep concerns about youth LSD use. The LSD hysteria also featured the discredited LSD chromosome damage theory. Amphetamine and barbiturate abuse remained a concern as well. The FDA just couldn’t handle law enforcement. Despite the Bureau and new law enforcement authorities in the 1965 Amendments, FDA remained reactive in policy. Investigators typically did not go out to seek persons violating the law, but waited to receive complaints.

Up to 1968, law enforcement functions were scattered among different federal agencies including the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, and the Bureau of Drug Abuse and Control (within the predecessor to HHS), the Bureau of Customs, and INS (within the Justice Department). The major innovation in 1968 Amendment was not a change in law, but something called “Reorganization Plan No. 1.” In that executive order, President Johnson combined the Bureau of Drug Abuse in FDA with the Federal Bureau of Narcotics in the Department of Treasury and made a third agency—the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD)—and putting that unified third agency in the Department of Justice, i.e., law enforcement. This Johnson creation BNDD, is of course the predecessor to DEA.

But because drug abuse continued to escalate—particularly among youth—Congress continued legislating as well. And with relatively little debate, it enacted a small new amendment: the Drug Abuse Control Amendments of 1968. This 1968 Amendment is fairly obscure, and it didn’t do very much. In the annals of history, it gets overshadowed by the CSA that came two years later. But the 1968 Amendment did something extremely important under the auspices of protecting youth: it made simple possession, even for personal use, a federal crime. Making mere simple possession a misdemeanor, some thought, would “discourage” young people from taking drugs.

(Side note: a contemporary Gallup poll showed 1% of college students had tried LSD and another found 10% in the general population had tried LSD. Although I have no way of reviewing the accuracy of these polls, I do note that psychedelic drug use today doesn’t appear to be less.)

It is hard to overstate the philosophical shift of this minor law. Until 1968, courts described the lawfulness of a federal law outlawing mere possession of a drug for personal use as “doubtful” and “dubious.” One court, for example, remarked:

Still, by the use of that power, Congress may not go beyond the powers delegated to the federal government under the Constitution of the United States. Congress may control traffic in narcotic drugs in accordance with its power over interstate and foreign commerce and under its tax power but its ability to declare mere possession of a narcotic drug unlawful is doubtful.

This is the first time that the federal government criminalized a passive drug activity, thus treating drug users—addicts—as criminals. And it is here, in my view, under the auspices of protecting the youth from themselves, where the drug policy conversation takes the bad turn. From here on, drug abuse/addiction begins to be viewed first and foremost as a crime and punishment matter, not public health issue.

Let me be clear about this as well: if you follow the Supreme Court’s recent commerce clause jurisprudence and read Raich correctly, there’s a persuasive, likely winning argument that the federal prohibition on simple drug possession is not and has never been constitutional. In other words, the federal government has no authority to penalize mere drug possession and use because possessing drugs is not an economic activity. If you can find the money, I’d take a swing and start moving the drug policy pendulum the other direction. Sadly, industry and deep pockets appear more interested in padding bottom lines, the FDA approval process, psychedelic vanity projects, complex drawn-out legal campaigns, or the like over a simple laser-shot lawsuit with substantial merit that could radically change the drug policy conversation. Whatever. I digress…

4.

Despite the creation of BNDD consolidating enforcement authority in DOJ, up to 1970, different regulatory regimes applied to different classes of substances. Two distinct sets of laws regulated narcotics and amphetamines, for instance. Most legislators and government officials saw a need to consolidate/rationalize this patchwork of drug control laws. Hence, the CSA.

But who would administer that unified system of drug control remained hotly disputed. Today, to some, that law enforcement reigns supreme over drug control may seem like a given. But in the months leading up to the CSA’s enactment, however, that notion was very much up in the air. Two factions formed: a group that thought the Health, Education, and Welfare Department should have primary responsibility for regulation and another that wanted the Justice Department to take the lead.

The American Psychiatric Association, for example, objected to the arrangements:

[I]t is our sense that the medical contribution to the national program to combat addiction and drug abuse in the form of expanded research, training and treatment in the field will be better nourished under the aegis of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare than under the Department of Justice. The former is traditionally oriented toward the unfortunate; the latter is traditionally oriented toward the punishment of offenders.

This hotly debated issue is worthy of an essay on its own. Many, many hearings were held. Suffice to say, at its very core lies the most important value question in drug policy: is drug abuse and addiction primarily a public health or crime/punishment matter?

In the end, we know what won. The CSA gave the ultimate authority on national drug control to law enforcement, but with a caveat: findings of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (today HHS) bind DEA. Thus, in scheduling a compound, DEA must first obtain the recommendation of HHS, whose recommendation binds the agency on medical/scientific factors, and if HHS recommends that a drug or other substance not be controlled, DEA can’t control the drug.

5.

In July 1973, President Nixon issued Reorganization Plan No. 2. This plan merged other law enforcement agencies into BNDD to establish the Drug Enforcement Administration—a single unified drug law enforcement agency to administer a unified drug control framework and rule them all.

My Billion Dollar Idea: Reorganization Plan Z

Far be it from me to champion the FDA, but if the federal government must regulate “dangerous” drugs nationally, it should do it under the auspices of an agency charged to protect the public health. As it happens, this agency already evaluates drugs, does science, and regulates other matters related to the public health and safety. We do not need a specialized law enforcement agency with a $3 billion budget sitting inside of the Justice Department telling us about the abuse and medical value of substances. Whether it does a good job or not, the FDA does this already.

With this in mind, it would be perfectly sensible to further consolidate as follows:

Transfer all functions relating to drug control—including scheduling and setting manufacturing quotas—back to FDA;

Fold what’s left of DEA’s enforcement operations into the already existing Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF), and by extension, to do what ATF already does: focus federal enforcement of drug laws on large-scale drug trafficking associated with criminal organizations.

Not only does this type of reorganization—sending regulation/control to FDA and folding large-scale enforcement into ATF—make sense from a policy perspective, it would save billions in taxpayer money. In corporate America, they have a word

Two agencies already do what DEA does. And together, without DEA, they can do better. There isn’t anything intrinsic to fentanyl analogues or methamphetamine that requires having a separate agency with a separate bureaucracy. ATF can bust illegal trafficking of alcohol, tobacco, guns, explosives and…drugs. Let law enforcement do law enforcement. Also, let the public health people do public health. Having a third bastardized hybrid agency packed with cops/bureaucrats that does both and is good at neither is bloat.

For starters, DEA’s sprawling bureaucracy screams downsizing:

Let’s break open just one of those bubbles: the Office of Diversion Control (four bubbles down in Operations Division).

These sub-subsections go deeper. Each of the folks above is a Section Chief, after all.

Now, let me illustrate how Reorganization Plan Z works.

First, add “drugs” to ATF.

The redundancies between ATF and DEA’s enforcement arms are impossible to escape. Often, ATF and DEA work together. Both agencies use confidential informants. Same deadly force policies. Sometimes, they share office space. Even the special agents look the same. Without the agency name stamped on their outfits, you wouldn’t know the difference:

Second, take the rest of the CSA out of DEA’s hands and put it with FDA. For example, drug scheduling. This is how it works today under Section 811(a):

DEA makes scheduling decisions through a complex administrative process requiring participation by other agencies and the public. DEA may undertake administrative scheduling on its own initiative, at the request of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), or “on the petition of any interested party.” With regard to the last route for initiating administrative scheduling, the DEA Administrator may deny a petition to begin scheduling proceedings based on a finding that “the grounds upon which the petitioner relies are not sufficient to justify the initiation of proceedings.” Denial of a petition to initiate scheduling proceedings is subject to judicial review, but a court may overturn a denial only if it determines that the denial is arbitrary and capricious.

Before initiating rulemaking proceedings, DEA must request a scientific and medical evaluation of the substance at issue from the Secretary of HHS. The HHS Secretary has delegated the authority to prepare the scientific and medical evaluation to FDA. In preparing the evaluation, FDA considers a number of factors, including the substance’s potential for abuse and dependence, scientific evidence of its pharmacological effect, the state of current scientific knowledge regarding the substance, any risk the substance poses to the public health, and whether the substance is an immediate precursor of an existing controlled substance. Based on those factors, FDA makes a recommendation as to whether the substance should be controlled and, if so, in which schedule it should be placed. FDA’s scientific and medical findings are binding on DEA. Furthermore, if FDA recommends against controlling a substance, DEA may not schedule it.

Upon receipt of FDA’s report, the DEA Administrator evaluates all of the relevant data and determines whether the substance should be scheduled, rescheduled, or removed from control. Before placing a substance on a schedule, the DEA Administrator must make specific findings that the substance meets the applicable criteria related to accepted medical use and potential for abuse and dependence. DEA scheduling decisions are subject to notice-and-comment rulemaking under the APA, meaning that interested parties must have the opportunity to submit comments on the DEA Administrator’s decision before it becomes final.5

The redundancy is palpable. There is no reason why DEA, a law enforcement agency, should review FDA’s scientific/medical evaluation. I’m not saying DEA is incompetent; in my experience, DEA has qualified, competent, hardworking professionals. Rather, I’m saying, DEA is redundant. It adds no value. Nobody at DEA offers relevant expertise that can’t already be found at FDA’s CDER. So, rather than the dual-referral dog-and-pony show we have now, just let CDER do it all. Let the pretext of science determine scheduling, not law enforcement vagaries.

Here is my new downsized version:

FDA makes scheduling determinations through a simple administrative process allowing for public participation, either on its own initiative or on a petition from an interested person. FDA considers a number of factors in choosing a proper schedule for a drug or substance, including the substance’s potential for abuse and dependence, scientific evidence of its pharmacological effect, the state of current scientific knowledge regarding the substance, any risk the substance poses to the public health, and whether the substance is an immediate precursor of an existing controlled substance. FDA determines an appropriate schedule based on these factors and similarity to already scheduled drugs. In addition, in the case of an NDA, FDA may consider REMS to ensure risks of abuse do not outweigh benefit.

The same can be said for Schedule I registrations, which right now, requires both FDA and DEA sign-off. For the record, I’m for abolishing Schedule I entirely. The arguments justifying its existence are thin and easily refuted. But abolishment aside, the dual referral process for registering Schedule I researchers is asinine. In a bill that seeks to ban fentanyl analogues (I’m mostly agnostic) Congress is also attempting to rewrite aspects of the CSA to fix some of these issues. While some of the fixes are laudable, in many ways, this is another Rube Goldberg solution that papers over the deeper structural issue: We have two agencies playing ping-pong with each other on controlled substance regulation. If “science” is what matters, just let FDA do it all.

Of course, Reorganization Plan Z may not be a perfect solution. But in terms of what can realistically be achieved in the next decade in federal-level drug reform, my view is that this type of reform might actually within reach. To me, reorganizing responsibilities for regulating controlled drugs comes right after (1) abolishing or reforming Schedule I and (2) providing public funding for medical research into Schedule I substances. Notably:

Reorganization does not require ceding one inch—rhetorical or otherwise—on the War on Drugs. The ATF-DEA agency is still busting up drug orgs, just under the umbrella of a single agency;

Moving drug control functions from DEA to FDA may even draw allies from the pharma lobby; and

Given the cost-savings, it might be something that could get bipartisan support.

At minimum, the federal government should convene an interagency commission to discuss the reallocation of drug control authority.

Conclusion

@RonanDLevy’s days of tweeting inane vacuous aphorisms may be behind us, and the body of work lost to the ages. But fear not friends. While coding RonanGPT, I managed to preserve one of the best.

I give you a stunning display—peak authentic inauthenticity—that will satiate your irony needs for the next decade:

In short, be original.

XOXO,

Matt

By the way, I’m totally cool with a luxury ketamine or psychedelic clinic whose mission is to serve rich people, price out poor people, and make money. Be the Chanel purse of psychedelic therapy. Just own it. Be authentic about it. Don’t pretend to be something else and try to sell us on a BS notion that by providing enlightenment for Rich White Men, you will enlighten everyone else.

I hereby dedicate the code to the public domain,

See what I did there? Made a patent joke and contradicted the previous sentence. Genius!

Think racism or Nixon started the War on Drugs? Ha! Convenient narrative, to be sure, but one that is way too simple and doesn’t squarely align with all the facts. Nor is the CSA entirely to blame. Rather, as I explain, in many ways the CSA consolidated many concepts that existed in predecessor laws.

Actually, if an interested person so requests, the scheduling process is subject to an esoteric process known as formal rulemaking hearing. Topic for another day.

Thank you for illuminating the US drug policy's spider web. I grew up between Paraguay and Brazil. DEA (pronounced 'thea') meant helicopters and small planes buzzing above us. Often spraying the maconha (cannabis) fields, which translated in supply and demand game. US supremacy reveal how most countries surrender sovereignty, they follow head first an ill conceived notion to control the bond between nature and human.