Schedule VI

The worst cannabis reform proposal yet

A new cannabis reform proposal is making the rounds. The organization behind the idea calls itself the “Schedule 6 Foundation.” And judging by the splashy ads for the group that now appear at the top of every page of Marijuana Moment, it has the financial backing of another company called AB46 Investments LLC:

I don’t know how much that kind of advertising costs. I bet it ain’t cheap. That means somebody out there really likes this idea. Keep that in mind as you read the rest of this post because, as I’ll explain, this proposal may be the worst cannabis reform idea I’ve seen yet—and that’s saying something. The question thus becomes why would anyone invest so much time and money in such a flagrantly terrible idea?

I offer some possible answers to that question at the end of this post. First, though, I’ll summarize the proposal and explain why it’s so remarkably bad.

The Proposed Amendment

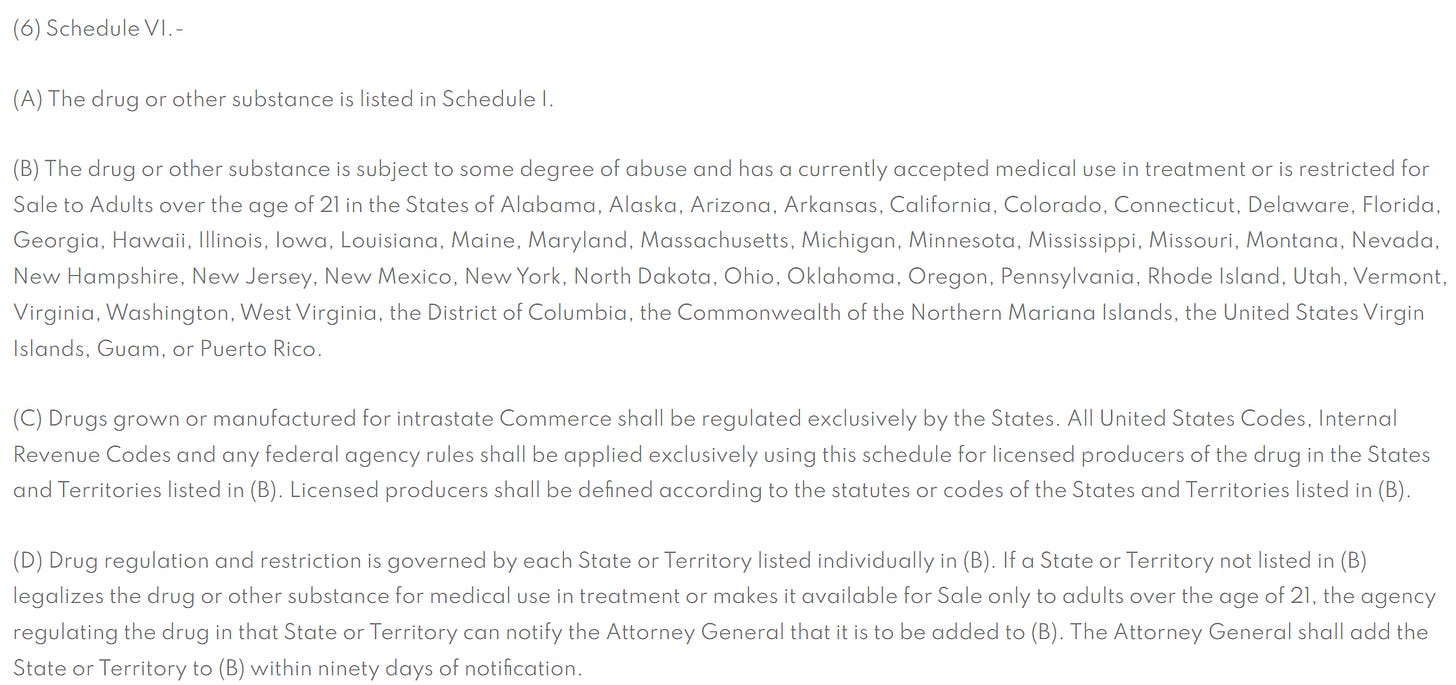

The basic idea, apparently, is to amend the CSA to add a new “sixth” schedule—one designed to “preserve [states’] rights to control & regulate marijuana a.k.a. cannabis.” This “Schedule VI” would be for substances that

are in schedule I and

are “subject to some degree of abuse and ha[ve] a currently accepted medical use in treatment” OR are “restricted for Sale to Adults over the age of 21” in one of the 37 states and 4 territories that have legalized cannabis for medical and/or adult use.

If “grown or manufactured for intrastate Commerce” by state-licensed “producers,” these schedule VI substances would be subject to exclusive state regulation. And if another state were to legalize such a substance for medical use or “for Sale only to adults over the age of 21,” it would be free to notify the Attorney General who would then have 90 days to add that state’s production of the substance to schedule VI.

Here’s a screen shot of the full text of the proposed amendment for context:

According to the Schedule 6 Foundation, this amendment would “solve[] a litany of problems” with federal cannabis policy, including, for example

“resolv[ing] the erroneous application of the 280E tax code”

providing cannabis businesses “[a]ccess to traditional banking & merchant services as well as American stock exchanges”

“allow[ing] universities & research institutes that receive federal funding to legally conduct studies around the medical uses of cannabinoids & terpenes using the existing State & Territorial supply chain”

“allow[ing] veterans access to a diverse set of cannabis products to mitigate the effects of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder”

allowing “[r]egistered patients [to] use medical cannabis” without being “subjected to additional federal taxes” and “while maintaining their Second Amendment rights”

Having introduced its “simple, elegant political solution” for “American cannabis,” the Schedule 6 Foundation invites “licensed U.S. cannabis operators, cannabis state associations, educational & research institutions, related ancillary businesses, and cannabis investors” to “apply for membership.”

For reasons I’ll explain next, your tireless authors here at OnDrugs will not be applying.

Why This Is a Terrible Idea

There’s a lot wrong with this proposal—far too much to cover in this lone post. So I’m just going to highlight what I believe are its three biggest flaws:

By requiring cannabis to remain in Schedule I to benefit from Schedule VI, the Foundation renders its entire proposal internally incoherent and self-defeating.

No medical marijuana would qualify for Schedule VI placement under the proposed amendment as written, meaning the Foundation’s promises about solving problems for veterans and patients are bogus.

Even if the proposal weren’t self-defeating for reasons 1 & 2, its failure to address treaty issues and section 811(d)(1) of the CSA would render it useless anyway.

The Proposed Amendment Is Self-Defeating

The biggest problem with the proposed amendment is its requirement (part (6)(A) of the proposed amendment) that to be eligible for Schedule VI, a “drug or other substance” must be “listed in Schedule I.” That provision renders the entire proposal absurd. If, as the Schedule 6 Foundation claims, its proposal would “remov[e] cannabis from Schedule I,” then, according to the plain language of Part (6)(A), it would also render cannabis ineligible for Schedule VI and the “litany” of benefits that supposedly come with it.

If, by contrast, the Schedule 6 Foundation is mistaken in claiming that its proposal would remove cannabis from Schedule I, then its Schedule VI amendment would be just as absurd. If the proposed amendment wouldn’t remove cannabis from Schedule I, then it wouldn’t address any of the problems stemming from cannabis’s Schedule I classification. That includes the 280E tax problem, banking, obstacles to research, veteran access, and more.1

Put simply, by tying the benefits of Schedule VI to keeping cannabis in Schedule I, the Foundation has guaranteed none of those benefits will ever materialize.

No Medical Marijuana Would Qualify for Schedule VI

Recall that, under the proposed amendment, two classes of substances would qualify for Schedule VI:

Those that are “restricted for Sale to Adults over the age of 21” under state (or territory) law, and

Those that have a currently accepted medical use in treatment.

States and territories that have legalized medical marijuana have not restricted it for sale to adults over the age of 21. As a result, medical marijuana could qualify for Schedule VI only if it has a currently accepted medical use in treatment.

But DEA, FDA, and federal courts all agree that the fact that states (and licensed doctors practicing within their borders) have accepted of cannabis’s medical utility does not prove that cannabis has a currently accepted medical use in treatment under the CSA. See 21 U.S.C. 812(b)(1) (identifying substances eligible for Schedule I classification as those that, among other things, have no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the U.S.) If they’re right about that, then medical marijuana does not have a currently accepted medical use in treatment and therefore would not qualify for Schedule VI under the proposed amendment as written.

And even if they’re wrong, medical marijuana still wouldn’t qualify for Schedule VI. Why? Well, if medical marijuana does have a currently accepted medical use in treatment, then it no longer qualifies for Schedule I classification. See 21 U.S.C. 812(b)(1)(B) (only substances with no currently accepted medical use in treatment qualify for Schedule I). And under Part (6)(A) of the proposed amendment, if medical marijuana isn’t “listed in Schedule I,” it can’t be listed in Schedule VI.

Because medical marijuana would not and could not qualify for Schedule VI, the Foundation’s proposal wouldn’t help those that need help the most: patients and veterans struggling under the federal government’s nonsensical approach to medical marijuana.

The Treaty Trap Strikes Again

Finally, even if I’m wrong about everything I’ve said so far, the proposed amendment would still be useless because it fails to address U.S. treaty obligations with respect to cannabis and section 811(d)(1) of the CSA.

The U.S. is a signatory to a U.N. drug control treaty called the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. Article 36 of that treaty requires the U.S. to prohibit most “cultivation, production, manufacture, extraction, preparation, possession, offering, offering for sale, distribution, purchase, sale, delivery on any terms whatsoever, brokerage, dispatch, dispatch in transit, transport, importation and exportation of [cannabis],” as well as “[i]ntentional participation in, conspiracy to commit and attempts to commit, any of such offences, and preparatory acts and financial operations in connexion with [those] offences.”

To make sure the U.S. complies with those obligations, Congress added section 811(d)(1) to the CSA. That provision requires DEA to place substances, including cannabis, in the CSA schedule DEA “deems most appropriate to carry out [U.S.] obligations” under the Single Convention.

Because the free-cannabis Gloryland that the Schedule 6 Foundation has in mind does not jibe with U.S. obligations under one of those treaties (at least as far as DEA/DOJ—the authoritative interpreters of those treaties under federal law—are concerned), DEA would be obligated under section 811(d)(1) to remove it from Schedule VI and place it another schedule (likely Schedule I or II). And because the proposed amendment leaves section 811(d)(1) unchanged, it basically guarantees that any benefits it might gain for cannabis would be very short-lived.

Conclusion: Why Would Anyone Pay for This?

In the intro to this post, I noted that somebody (AB46 Investments LLC and possibly others) liked the Schedule 6 Foundation’s idea so much that it has paid to fund an advertising campaign promoting it. Yet, I’ve demonstrated here that the proposal isn’t just bad—it’s downright awful. And while this is probably the worst cannabis-reform proposal I’ve seen since I’ve been keeping up with this stuff, it isn’t the first very bad one. Indeed, I’ve written about many others in prior posts. So what’s going on? Why would stakeholders, investors, and lawmakers put so much time, energy, and money behind so many obviously bad proposals? This one—creating a new schedule on top of the CSA—is particularly bad. It is tantamount to building a castle on a swamp.

I’ve been pondering that question a lot lately. Here are some possible answers.

My guess is that the people offering these bad proposals aren’t really invested in achieving effective reform. Instead, they are likely invested in appearing as though they are working toward reform. There is a big difference. Perhaps it’s more important to them (especially heading into election season) to look like they’re doing something for veterans, research, cannabis, etc. than to actually do the work necessary to craft a bill that would actually achieve real results.

Why would candidate Biden promise cannabis reform, say that no one should be in jail for using drugs, etc. and then do nothing for the cannabis movement once he became President Biden? Maybe candidate Biden knew those promises would get him elected, so he used them for his own purposes. Maybe now that he’s President Biden, the status quo on most drug reform issues doesn’t bother him so much anymore.

Why would an organization propose a change to federal law that wouldn’t solve federal problems at all? Maybe because it is backed by folks who are in the habit of ignoring federal law because they make loads of money under state laws. In other words, if someone is profiting under federal prohibition, they probably don’t mind the status quo too much. Sure, they might want better banking access, more advantageous tax laws, and so on. If they can achieve those objectives without too much trouble, they’ll certainly do that. Also, the moment the problem is actually solved, there is no more work to do, and no reason for some of these groups to exist or reason for them to whine. Bottom line: don’t expect people who profit from the status quo or whining about the status quo to trip over themselves to upset it or fix it through major federal policy reform.

To be clear, I’m not sure I’m correct about anyone’s motivations here. I’m also not faulting businesses for focusing on their bottom line (I most certainly do fault lawmakers and the President for their part in all this, of course). I just find myself seeing obvious problems with one reform proposal after another and have to ask myself why this continues.

That’s my answer for now. If you have a better one, please share it. In the meantime, why continue these masturbatory legislative exercises? If we really want to fix this problem, we’re going to have start from scratch.

See 26 U.S.C. 280E (barring companies that “traffick[] in controlled substances (within the meaning of schedule I and II of the Controlled Substances Act) which is prohibited by Federal law or the law of any State in which such trade or business is conducted” from deducting ordinary business expenses) (emphasis added); Black & Galeazzi, Cannabis Banking: Proceed With Caution, American Bar Assn., Feb. 6, 2020 (explaining that much of the cannabis industry’s struggle to access banking services stems from its status as a Schedule I substance under federal law); 21 U.S.C. 823(f) (imposing strict requirements on registrations to research Schedule I substances); this monograph (detailing obstacles to cannabis research resulting from its status as a Schedule I substance); Public Law 101-226 (Drug Free Schools and Campuses Act, which, along with related regulations (41 CFR § 102-74.400; 48 CFR § 52.223-6; and 34 CFR § 86.2) bars all persons entering in or on Federal property, recipients of federal funds administered by the U.S. Department of Education, and Federal Contractors at their workplace are prohibited from use or possession Schedule 1 controlled substances).

A new scheduling category could bring in a host of challenges for a poorly understood area of drug policy, especially after legislative processes. The legislative process would undoubtedly alter the proposed language. It unlikely a new scheduling category would be created that doesn’t follow the same logic as the existing schedules. For example, would all drugs and substances that are not scheduled, then have to then undergo an assessment or be automatically included under the definition of a schedule VI drug (i.e., products related to alcohol, tobacco, OTC, and even prescription drugs like epidiolex)? This could open the door to scheduling unscheduled products. Advocates are making the argument that this approach would mean the DEA, FDA, NIDA, and federal agencies would not be involved...

Yep, it could be written better, like saying DEA has no authority to remove anything Congress places in Schedule VI and that it clearly supersedes anything in the international treaties. It could have further clarity, but that would fix most of your objections to it. My main problem with it is it does not include an application under 21 C.F.R. 1307.03 (21 U.S.C. 822(d)) for an immediate federal exemption. Why wait for Congress to act?