U.S. accession to the Single Convention marked the culmination of decades of work for Harry J. Anslinger. Since the very early days of his notorious tenure as the first Commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, Anslinger sought to use treaty obligations to permit Congress to override traditional state authority by enacting federal legislation directly banning marijuana use. His first attempt failed in 1936, forcing Anslinger to settle for indirect federal marijuana control in the form of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. Thirty years later, when the United States was considering the Single Convention, Anslinger saw his chance and got to work promoting U.S. accession. His scheme, which I call “Anslinger’s Treaty Trap,” worked, and we have been caught in Anslinger’s Trap ever since.

In 1967, Harry J. Anslinger came out of retirement to appear before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in support of United States accession to the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961. See Single Convention, 18 U.S.T. 1407. Noting that “[s]everal groups in the United States loudly agitating … to legalize [marijuana] use,” Anslinger argued that the United States should use “treaty obligations to resist” their efforts:

Another important reason for becoming a party to the 1961 convention is the marihuana problem .... Several groups in the United States are loudly agitating to liberalize controls and, in fact, to legalize its use .... If the United States becomes a party to the 1961 convention we will be able to use our treaty obligations to resist legalized use of marihuana. This discussion is going on all over the country, in many universities, and in fringe groups, and it is rather disturbing.

Anslinger had long argued that the treaty power was essential to federal marijuana control. During his early years at the helm of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, Anslinger was reluctant to pursue marijuana at all. D. Musto, The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control (3d Ed. 1999), Ch. 9. For one thing, he didn’t think the drug was causing serious problems. Id. For another, the stuff “grew like dandelions” and had “a few legitimate uses.” Id. As a result, Anslinger insisted that federal control would require full prohibition. In his view, a federal marijuana ban riddled with exceptions for medical uses and the like would be an enforcement nightmare. Id.

Trouble was, federal legislation banning marijuana use directly was out of the question for another reason: the U.S. Constitution. After meeting with a brain trust of experts in 1936, Anslinger wrote a confidential memo to another senior Treasury Department official named Stephen B. Gibbons, explaining that “under the taxing power and regulation of interstate commerce it would be almost hopeless to expect any kind of adequate control.” Id. n.30 (quoting confidential memo). Anslinger was right. Such public health and safety measures were seen as quintessential exercises of the “police powers” reserved to the states under the Constitution. See, e.g., Whalen v. Roe, 429 U.S. 589, 603 n.30 (1977) (States retain “broad police powers” under Tenth Amendment to regulate “the administration of drugs by the health professions”); Linder v. United States, 268 U.S. 5, 18 (1925) (“[D]irect control of medical practice in the states is beyond the power of the federal government.”). What Anslinger needed then was a way to override traditional state police powers. For that, he turned to a 1920 Supreme Court opinion authored by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. See Missouri v. Holland, 252 U.S. 416 (1920).

David Musto describes Anslinger’s scheme in detail in Chapter 9 of his book The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control:

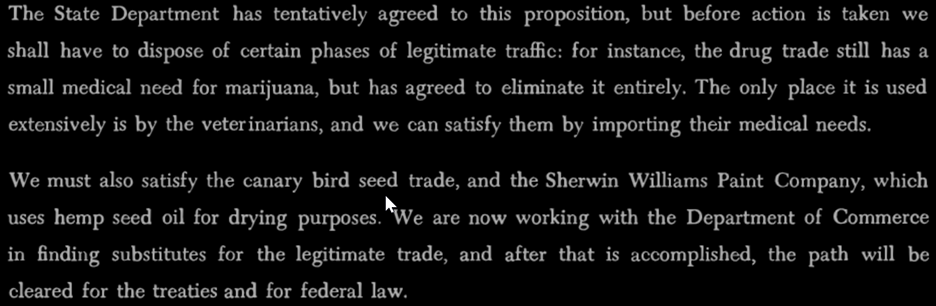

Anslinger’s confidential memo went on to explain that for his plan to work, the federal government would need to close off the legitimate channels of marijuana traffic ahead of time. The pharmaceutical industry, for example, had a “medical need for marijuana,” but Anslinger reported that it had already agreed to “eliminate it entirely.” Id. As for the other “details,” Anslinger was already working backchannels:

In June 1936, Anslinger traveled to Geneva to pitch the necessary marijuana control treaty to the Conference for the Suppression of the Illicit Traffic in Dangerous Drugs. The other delegations balked, however, so Anslinger’s proposal never made it into the final agreement. Of the 27 nations in attendance, the United States was the only one that refused to sign the resulting convention. Id.

When Anslinger’s treaty idea failed, the Treasury Department got to work on its fallback plan: indirect federal marijuana control through a transfer tax. The result was the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which remained in place until the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1969. See United States v. Leary, 395 U.S. 6 (1969). Anslinger’s appearance before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to promote his treaty scheme again in 1967 (while Leary’s case was making its way to the Supreme Court) was therefore very well timed. It also worked: The Single Convention entered into force for the United States on June 24, 1967. See Single Convention, 18 U.S.T. 1407.

The Single Convention is not self-executing. It depends instead on the subsequent implementing legislation of signatory states to become binding on as a matter of their domestic law. When the United States became a party in 1967, no additional federal legislation was necessary to implement the Single Convention’s marijuana control requirements. The combination of the ill-fated Marihuana Tax Act and state marijuana laws “allow[ed] virtually no legitimate use of marijuana.” See David Murray Van Atta, Effects of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs on the Regulation of Marijuana, 19 Hastings L. J. 848, 854 (1968). When the Supreme Court declared the Marijuana Tax Act unconstitutional in Leary, however, the stage was set for Congress to act on Anslinger’s plan for legislation banning marijuana at the federal level under the treaty power.

Anslinger’s dream became a reality with the enactment of the Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, commonly known as the Controlled Substances Act or CSA. See 21 U.S.C. § 801 et seq. “[A] number of the provisions of [the CSA] reflect Congress’ intent to comply with the obligations imposed by the Single Convention.” Control of Papaver Bracteatum, 1 Op. O.L.C. 93, 95 (1977) (citing 21 U.S.C. §§ 801(7), 811(d)(1), 958(a)). See also S. Rep. No. 91-613, at 4 (1969) (“The United States has international commitments to help control the worldwide drug traffic. To honor those commitments, principally those established by the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, is clearly a Federal responsibility.”). From then on, the United States was locked into a regime of stringent controls on the cultivation, manufacture, distribution, and even mere possession of marijuana—regardless of state laws to the contrary. See Single Convention, 18 U.S.T. 1407, art. 4; id. art. 36 (signatory countries must impose criminal penalties for the “cultivation, production, manufacture, extraction, preparation, possession, offering, offering for sale, distribution, purchase, sale, delivery on any terms whatsoever, brokerage, dispatch in transit, transport, importation and exportation of drugs”).

UPDATE: Since I wrote this post, HHS has recommended that DEA move cannabis to schedule III, concluding that widespread state legalization and regulation of its medical use at the state level proves it has a currently accepted medical use. Under the statute, that scientific and medical determination is binding on DEA unless accepting it would interfere with U.S. treaty compliance. Matt and I recently wrote a law review article explaining why Anslinger’s Treaty Trap is unconstitutional. Here’s hoping DEA doesn’t make us prove it.

I didn't realize that Anslinger bypassed medical recommendations and used Interntional treaties to begin cannabis regulation. This decision is still affecting us today. In this legal case, the lawyer is not able to question the Interntional treaties even though they now are used to criminally bypass other laws. All of which has created a containment system to protect profits. Here is the article I wrote on a connected case.

https://open.substack.com/pub/wutaiwatcher/p/us-supreme-court-petition-big-pharma

Hello! Very interesting arricle but I am not convinced by the fact that Anslinger won the argument. I have read through the League of Nations and United Nations archives related to cannabis (1926-1961) and found that the US position failed to be the one followed in many instances. Ansliger even left the room and did not take prt in the end of the Single Convention’s negociations because he found that his ideas were not being properly reflected in the draft treaty. William McAllister documents this very convincingly in his thesis and his 2000 book “Drug Diplomacy in the 20th Century”. In recent decades, historiand have shown that Anslinger and the US’s role was way less important than that of countries such as Egypt, when trying to push global cannabis prohibitions. I have published last montj a report “High Compliance” which also re-analyses the text of the Convention and shows not only it is NOT a cannabis prohibition treaty, but it contains workeable exemptions giving governments full socereignty to regulate “other than medical and scientific uses” of cannabis. I would be happy to discuss anf share some reference with you eventually! All the best. Kenzi