Back in March, against the recommendation of the Solicitor General, the Supreme Court heard argument in the case Amgen Inc., v. Sanofi. The case is about the “enablement requirement” of Section 112 of the Patent Act. The oral argument is available here. The question presented (emphasis mine) was as follows:

Whether enablement is governed by the statutory requirement that the specification teach those skilled in the art to “make and use” the claimed invention, 35 U.S.C. § 112, or whether it must instead enable those skilled in the art “to reach the full scope of claimed embodiments” without undue experimentation-i.e., to cumulatively identify and make all or nearly all embodiments of the invention without substantial “’time and effort.’” In other words, can the requirement of “enablement to the full scope” continue to render genus claims to biotechnology inventions invalid?

Last month, the Supreme Court handed down a unanimous decision.

On its face, the opinion does not change the status quo, leaving in place the longstanding “undue experimentation” test for determining whether a patent claim is enabled. Nonetheless, as it is a SCOTUS patent case, it could impact pharmaceutical patents—and therefore, by extension, psychedelic patents and psychedelic IP portfolios. Applying principles laid down in Amgen can help separate wheatty from chaffy IP. For example, members of the MindMed-Liechti patent farm.

Hence, this essay.

The Enablement Requirement

Let’s start with basics.

A common defense to a charge of a patent infringement is that the asserted patent is invalid. Under 35 U.S.C. § 282, issued patents are presumed valid. In litigation, however, an accused infringer can overcome the presumption by providing clear and convincing evidence of invalidity.

The Patent Act lists several grounds to assert invalidity. Recall, for example, anticipation and obviousness—two defenses I’ve previously discussed in some detail. In general (with some important exceptions) a patent claim is not novel or new under Section 102 when it has been made or publicly disclosed before the priority date of a patent. Under Section 103, a patent claim is obvious when the differences between it and the prior art are small enough such that a person having ordinary skill in the art would have deemed the invention obvious at the time of the invention.

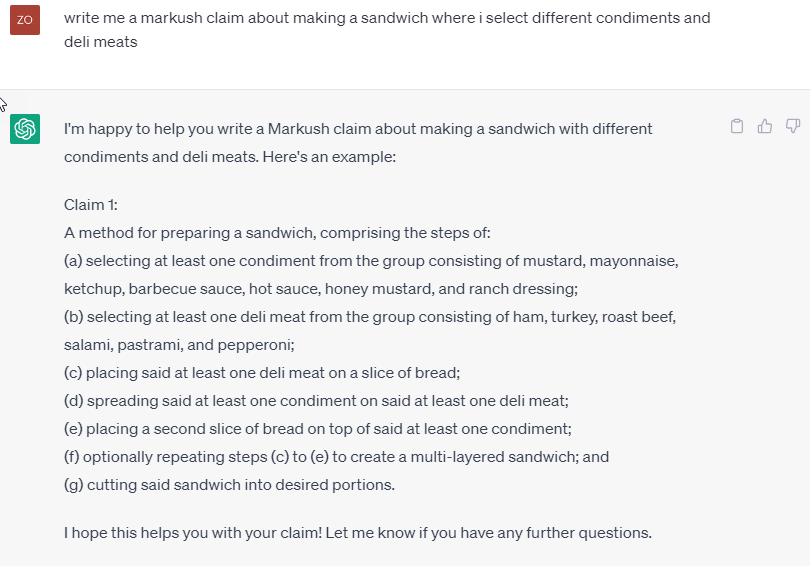

These two prior-art based invalidity defenses are “condition[s] for patentability” defenses, highlighted in yellow below in the text of 35 U.S.C. § 282.

As the above image shows, in blue, there is another class of invalidity defenses—“requirement[s] of section 112”—that is not based on prior art disclosures bur rather focus on the disclosure of the patent itself. Section 112(a), provides that a specification:

[S]hall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make and use the same, and shall set forth the best mode contemplated by the inventor or joint inventor of carrying out the invention.

Over the years, the Federal Circuit—the “Supreme Court of Patents”—and the Supreme Court have refined and broken out Section 112 into 3 distinct requirements:

Written description. A patent specification must contain a written description of the invention to show those of skill in the art what the invention is. The test for the sufficiency of the disclosure is whether the specification “conveys to those skilled in the art that the inventor had possession of the claimed subject matter as of the filing date.”

Enablement. A patent specification must allow the skilled artisan to make the claimed invention without “undue experimentation.”

Indefiniteness. Section 112 requires claims be written with a certain degree of clarity and precision. “A patent is invalid for indefiniteness if its claims, read in light of the specification delineating the patent, and the prosecution history, fail to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention.”

The Current Enablement Standard

An enabling disclosure is central to the quid pro quo of the patent bargain. The inventor advances the science by publishing an enabling disclosure in the patent specification so that one of skilled in the art can practice the invention. In exchange, the inventor gets a limited patent monopoly for a term of years. This is a key difference between a patent and trade secret. Trade secret law does not provide a monopoly; it only protects against misappropriation. But, because there is no disclosure bargain, the term of protection lasts so long as the trade secret stays secret.

Under prevailing Federal Circuit law, a claim is not enabled—and therefore invalid—if, after reviewing the specification’s disclosure, an invention would require “undue experimentation” to make or use. Courts make this determination as a matter of law according to factors enumerated in a case called In re Wands:

the quantity of experimentation necessary

the amount of direction or guidance presented

the presence or absence of working examples

the nature of the invention

the state of the prior art

the relative skill of those in the art

the predictability or unpredictability of the art, and

the breadth of the claims.

Importantly, over the years, the Federal Circuit has required the full scope of a claim be enabled. “A patentee who chooses broad claim language must make sure the broad claims are fully enabled,” meaning, a patentee that writes broad patent claims must make sure the entire scope of the claim can be practiced without “undue experimentation.”

The Genus-Species Problem

Patent claims are sometimes drawn to a genus, or a group defined by common characteristics. In contrast, a claim could be drawn to a species, i.e., a logical division of a genus. A genus claim is necessarily broader than a species claim.

A prototypical example of a genus claim is the Markush claim named after the 1925 Ex parte Markush case. A Markush-type claim recites a list of elements that can be alternatively used in a claim. Here is an example using my favorite patent prosecutor:

There’s a whole lot to say about Markush claiming—beyond what can be summarized in this essay. Generally, a valid Markush claim requires the alternate elements be substitutable and share a characteristic or property.

In the above ChatGPT example, the deli sandwich genus encompasses a number of sandwich species with different condiments/deli meats combinations, say, a honey mustard, turkey, and roast beef sandwich.

My combinatorics is rusty; I think the number of sandwich species that could be made with any subset of 7 condiments and 6 deli meats equals 8001.1 The enablement question would then ask if the specification taught a person of skill in the art how to make these 8001 sandwiches without undue experimentation.

The genus-species problem is important to patentability for several reasons. It is important, for example, for the purposes of anticipation. Generally, “[a] generic claim cannot be allowed to an applicant if the prior art discloses a species falling within the claimed genus.” Similarly, in some cases, a generic disclosure may anticipate everything within the genus. And of course, the genus-species problem is also important for enablement and written description: the more an inventor claims (genus) the more she must enable and describe.2

Prophetic Examples

Enablement also is an issue with “prophetic examples.” Prophetic examples are “routinely used in the chemical arts” used to describe reasonably expected future/anticipated results. Working examples, in contrast, correspond experiments or work that has already been conducted that yielded actual results.

In July 2021, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office issued a notice on “Properly Presenting Prophetic and Working Examples in a Patent Application.” The notice explains prophetic examples may be written in future or present tense—but not the past tense—to assist readers in differentiating between actual working examples and prophetic examples. A patent application does not need to have any working examples at all. It can be purely theoretical and predictive.

That’s a thing about patents—to get one, you don’t have to prove the invention works for its purpose. As the USPTO notice states, in Allergan, Inc. v. Sandoz Inc., the Federal Circuit opined that “efficacy data are generally not required in a patent application” and “a patentee is not required to provide actual working examples.” This is why one can patent the use of LSD treating food allergies without knowing if it works.3

To be precise, as the USPTO notice explains (citations omitted):

“Only a sufficient description enabling a person of ordinary skill in the art to carry out an invention is needed.” The courts have further cautioned that the presence of prophetic examples alone should not be the basis for asserting that a specification is not enabling; rather, a lack of operative embodiments and undue experimentation should be determinative.

The Ariad court addressed the use of prophetic examples in the chemical arts, stating that they “they certainly can be sufficient to satisfy the written description requirement.” But a “mere mention” of a “desired outcome” will not suffice. So, a prophetic example providing enough detail such that a non-expert can use the invention is enough. It isn’t necessary to verify results or know that a prophetic example is effective or achieves the intended purpose. As far as enablement is concerned, you just need to be able to do it.

Functional Claiming

A third enablement related patent issue has to do with functional claims. A functional claim describes an invention based on what it does (i.e., how it functions) as opposed to what it is (i.e. structure). Here is how the PTO, in the Manual for Patent Examination and Procedure (MPEP), describes functional claiming:

A claim term is functional when it recites a feature “by what it does rather than by what it is” (e.g., as evidenced by its specific structure or specific ingredients). There is nothing inherently wrong with defining some part of an invention in functional terms. Functional language does not, in and of itself, render a claim improper.

The following is an example of a functional claim, courtesy of OC Lawyer:

“a software program for organizing and displaying digital photographs, wherein the program is configured to automatically group photographs by date, time, and location.”

The claim is functional because one limitation is defined by what it does—automatically grouping photograph by metadata—and not by what it is.

By its nature, a functional claim is broad(er) in scope. Consider the example above. How many ways can one “automatically group photographs” based on date, time, and location? And because a functional limitation adds breath, it is also more likely to run into Section 112 enablement/written description problems. It can raise indefiniteness problems too, as functional language often obscures the boundaries of where the invention ends and the public domain begins.

Amgen v. Sanofi

Background

In 2014, Amgen sued Sanofi alleging the latter’s cholesterol drug Praluent infringed the Amgen patents. The posture of the case is simple: both Amgen and Sanofi patented PCSK9 antibodies (i.e., antibodies that bind to the PCSK9 protein) with different amino acid sequences, with Amgen holding the patent having an earlier priority date. With patent continuation practice, Amgen then sought a second generation patent that claimed priority back to the first patent and preceded the competition. The continuation patent sought to claim all antibodies that bind to certain amino acids on PCSK9, i.e., a functional claim.

Despite what the (soon to be private?) Reunion Neuroscience may say in a court filing patent law does not prohibit writing claims in a continuation to cover a competitors product after learning about that product, provided the original specification can support those claims. At least, that’s what the Federal Circuit said in Kingsdown.

Twice a jury found the asserted Amgen claims enabled. In both, however, the district judge threw out the verdict and concluded that the patent failed to enable the claims as a matter of law. And in both appeals, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district judge.

Enter the United States Supreme Court.