The first two installments of Psychedelic Patent Wars™ thrust us into the world of psychedelic patents by way of dumpster diving. Both looked at two garbage psilocybin applications floating around the United States Patent and Trademark Office (PTO).

In case you missed those or want a recap:

Examining these outliers can only teach so much, however. So, this installment takes a different approach and looks at some issued patents with bona fides: the Intranasal Ketamine Patents or Charney Patents. This installment, like the last, proceeds in parts. This part starts with background and the Charney Patents. The next part will pivot to the Esketamine or Janssen Patents.

These patents have been written about quite a bit, albeit not always accurately IMAO. And to my knowledge, nobody has done a deep dive.

But before we do that, let’s start with some preparatory work. First, I’m going to pick up a thread I left loose in earlier writing related to PCP. Then, I’ll wax a bit about patent prosecution. And then, we’ll look at the patents.

Time to drop in.

Ketamine: A Brief History

The history of ketamine begins with PCP.

Phencyclidine (PCP) is an synthetic arylcyclohexylamine first discovered in 1926, later made proprietary by pharmaceutical company Parke-Davis (today a Pfizer subsidiary). By the late 1950s, scientists had shown PCP to be a useful anesthetic in medicine. Initial reports in animals noted lack of sensation, hyperlocomotion, ataxia, catalepsy, and catatonic states. In humans, PCP produced intolerable emergence symptoms, such as delirium or psychosis.

Parke-Davis sold the drug under brand name Sernyl. But due to emergence symptoms, it quickly got shelved. So, Parke-Davis went searching for a new drug for use in humans while PCP continued to be used as an anesthetic in animals until the 70s.

Although emergence symptoms diminished PCP’s usefulness as medicine, it remained an experimentally useful compound. During the same period of robust experimental LSD research in the late 50s and early 60s, scientists also experimented with PCP. Like LSD, scientists used PCP to better understand the mind—particularly symptoms of schizophrenia. Indeed, PCP was called a “schizophrenomimetic drug.” And, as I mentioned before, scientists paying really close attention might have seen the potential to generate antidepressants out of the arylcyclohexylamine/NMDA antagonist class, of which ketamine is a member.

In search of a shorter duration PCP-like drug with better side-effects, Parke-Davis chemists made PCP analogues. And in 1962, Calvin Stevens, a chemist-consultant stumbled upon ketamine. Clinical studies then showed ketamine had safety and efficacy, without the intolerable emergence delirium of PCP. FDA approved ketamine hydrochloride (brand name Ketalar) as a rapid acting anesthetic in 1970. And quickly thereafter, ketamine saw field duty in the Vietnam War. Ketamine is a particularly effective military anesthetic. In 1985, WHO named ketamine an essential medicine.

Today, ketamine is still a preferred military analgesic and anesthetic either alone or in combination with other drugs due to its impressive safety profile as well as its potential to safely synergize with other classes of drugs. Indeed, one could say it is a wonder drug for certain applications, producing pain relief similar to morphine but with rapid onset.

Because ketamine is an approved drug, it was never placed into Schedule I. Indeed, up until 1999, it remained unscheduled. Ketamine was almost scheduled in the 80s, but DEA did not consider a yearly average of four documented instances of diversion or abuse to be legally sufficient to sustain a scheduling action. DEA continued to monitor the situation, however. And in 1999, after ketamine became a party drug, DEA placed ketamine in Schedule III.

Ketamine: A Novel Antidepressant Agent

The fact that ketamine never got placed in Schedule I is important and is directly related to its off-label discovery as a novel antidepressant agent. Remember, as stated earlier: if you really want to understand psychedelic patents and the development of psychedelic medicine generally—including the problems/issues therein—you need to “keep your third-eye peering at the regulatory process.”

Racemic ketamine had been reported to show antidepressant-like effects in animal models as early as 1975. Then, in the early 80s, scientists began to unpack the NMDA receptor antagonist properties of ketamine, PCP, and the drug class. Then, pre-clinical research from the 90s, led by Phil Skolnick1 , began to give strong clues that modulating the NMDA system could alleviate depression-like behaviors.

As early as 1990, Phil Skolnick and Ramon Trullas hypothesized that “substances capable of reducing neurotransmission at the NMDA receptor complex,” such as ketamine, “may represent a new class of antidepressants.” A 1996 article by Skolnick et al. entitled “Adaptation of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) Receptors following Antidepressant Treatment: Implications for the Pharmacology of Depression” made the following observation:

One rodent study gave good evidence of ketamine and another NMDA antagonist drug MK-801 acted as antidepressants. That study showed that concomitant administration of ketamine with the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine showed a greater reduction in behavioral depression than either drug alone.

Thus, by the turn of the century, ample preclinical literature supported a notion that ketamine might be an effective antidepressant properties. But the theory had yet to be clinically tested in humans.

The 2000 Berman study changed that: a double-blind placebo trial designed to specifically see if IV ketamine had antidepressant effects. The Yale investigators behind the Berman study were specifically aware of Skolnick’s research. But they did not expect the results: that ketamine would have a rapid and robust antidepressant effect. The Berman study showed that a single subanesthetic dose of ketamine improved depression rapidly—in less than 24 hours and significant improvement over placebo. And yet, according to Charney, one of the Yale investigators behind the Berman study, the study “had very little impact on the field.” The paper was only cited around 20 times per year.

Nonetheless, the Yale crowd continued researching and did more research under Grant No. 1Z01MH002857-01. And on March 22, 2006, Yale, HHS, and the Icahn School of Medicine filed a provisional application describing methods and compositions for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression using ketamine to protect the fruits of the research.

Patent Prosecution

Patent prosecution is the process by which a patent applicant works with the PTO to obtain a patent. As I mentioned in an earlier installment, the process is a bit like a negotiation or conversation with the patent examiner over claims.

In general, it follows a similar song-and-dance. A provisional application puts a stake in the sand on a priority date and initiates a one-year clock to file a non-provisional application. With a non-provisional application, the patent applicant proposes an initial claim set. The applicant asks for claims as new, non-obvious inventions adequately supported by the patent’s specification. The examiner either (a) agrees with that assessment or, far more likely (b) issues a non-final rejection of the claims. There are several grounds for rejection. Most commonly, claims are rejected as not new, obvious in view of a combination certain references, or because the specification does not support the full scope of the claims.

The vast majority of patents receive at least one non-final rejection. But if the examiner goes with (a), the claims are allowed and the patent issues. If the examiner goes with (b) and rejects the claims, the applicant gets an opportunity to amend the claims. An applicant may then narrow the scope to create distance between the claims and any prior art cited by the examiner and submit a revised claims to the examiner. Alternatively or in addition, the applicant can argue.

Rinse and repeat. A second or subsequent rejection from the examiner is a final rejection as long as the rejection does not include a new ground of rejection that doesn’t respond to an amendment of claims or new prior art disclosed by the applicant.

After a final rejection, the patent application is done, right? Wrong. Unfortunately, a “final” rejection is a misnomer. Little at the Patent Office is ever really final. Life at the PTO is pay-to-play. A final rejection just means that the applicant must pay an additional fee to continue by filing a “Request for Continued Examination” (RCE).2

In this way, patent prosecution is kind of like an arcade game. Sure, you can run out of lives. But if with another quarter, you get a fresh game.

And with enough quarters, you can play this game forever—or at least until you beat it and get a patent issued.

Each communication between the examiner and applicant generally takes months. Thus, on average, start-to-finish this process takes around 2 to 4 years. In some cases, prosecution can take much longer—particularly if there are multiple non-final rejections or multiple RCEs.

The PTO also has accelerated processes to speed up patent examination.

The Track One program is a first-class ticket for patent applications. It allows an applicant to pay $4,000 more for prioritized examination and receive a final decision usually in less than a year.

Accelerated Examination allows applicants to expedite prosecution similar to Track One, but costs less. Unlike Track One, however, Accelerated Examination requires more paperwork, including the submission of a pre-examination search prepared by the applicant and an examiner interview is required before the examiner issues a first office action. This program was used with the Candy Flip Patent, for example.

The Intranasal Ketamine Patents

Although filed in March 2006, the first and flagship Intranasal Ketamine Patent, U.S. Patent No. 8,785,500 doesn’t issue until 2014. The conversation between the examiner and Yale/HHS/Icahn (applicants) took almost double average. Let’s see why.

As discussed above, the inventors lodge the provisional on March 22, 2006. One-year less two days later, the non-provisional application is filed with an initial set of claims. Here is Claim 1:

Ketamine up the nose for treatment-resistant depression.

Today, in 2022, this claim might not seem novel or non-obvious. But think back to March 2006. Ketamine had been widely used as an anesthetic. (Also, John Lilly used ketamine to treat migraines and contact the “Earth Coincidence Control Office.”) But in Spring 2006, was it obvious to those in the art to administer ketamine through the nose to treat treatment-resistant depression? That is the legal question.

The patent examiner, in June 2010, said “yes.” In a non-final rejection, the examiner rejected the claims as obvious in light of the Berman and another reference called Rush, and further in view of Mermelstein.3

The examiner explained that Berman taught treating a subject with major depression with ketamine and suggested the use of an NMDA receptor modulating drug in treating depression. (True.) But Berman did not teach through-the-nose administration. (Also true.) But according to the examiner, Rush taught clinicians confronted with patients having treatment resistant depression to do one of two things: (1) discontinue treatment and being a new one (switching) or (2) add another treatment to an existing treatment (augmenting). Rush also taught a third switch and augment strategy, where one treatment is stopped while the other is continued. And if the claims were not obvious in light of the Berman/Rush combination, the third reference, Mermelstein, taught the safety of administering ketamine intranasally.

Thus, according to the examiner, it would have been obvious to combine these three references to get the claims:

In October 2010, the applicants responded and withdrew some claims. But rather than amend or narrow the remaining claims (such as Claim 1) to get around the Berman+Rush+Mermelstein combination, the applicants chose to argue and “traverse”—patent lingo for registering disagreement with the examiner's findings. The applicants conceded that Berman taught significant improvement in depressive symptoms with IV ketamine. But, they argued, Berman didn’t teach intranasal administration of ketamine for treatment resistant depression.

The patentee then argued about a 2007 Supreme Court case called KSR. In brief, in KSR, the Supreme Court overruled a prior test for obviousness called the “TSM” test or “teaching-suggestion-motivation” test. Under that test, a prior art combination would render a claim obvious only if there were some teaching, suggestion, or motivation to combine the references in the combination. Instead, the Supreme Court embraced a flexible approach to obviousness. For example, an invention could be “obvious to try” if it was the product of a choice from a finite number of identified, predictable solutions, with a reasonable expectation of success.

The applicants stated that it would not have been obvious to combine Berman (IV ketamine for depression) with the teachings of Rush (if at first you don’t succeed, try something else). They also argued that major depression (MDD) is not the same thing treatment-resistant depression (TRD), that Berman taught away from using ketamine because it induced perceptual disturbances, and that Rush taught that antidepressant therapies are “fungible” so “the likelihood of success with all therapies drops as the degree of resistance rises.” As to Mermelstein, the applicants conceded that the reference taught intranasal administration of ketamine, but noted that nothing in Mermelstein suggested intranasal administration as an antidepressant. Back to you, patent examiner.

In December 2010, the examiner issued a final rejection. She “fully considered” the above arguments and found them to be “not persuasive.” The patent specification defined TRD as unipolar depression that did not satisfactorily respond to one or more treatments. Thus, the examiner explained, because Berman disclosed patients having met DSM criteria for recurrent unipolar depression, it would have been obvious to use ketamine for TRD. The examiner also did not buy the applicants’ spin on Rush. According to the examiner, Rush described switching therapies as a common and well known medical practice to treat TRD with up to 50-60% of patients. (Disclosure: I’m not a doctor—I only play one in print—but that seems reasonable.) The examiner suggested the applicants file a Rule 132 declaration to establish a surprising and unexpected result.

What is a Rule 132 declaration, you say? A Rule 132 declaration is an oath or affirmation submitted to provide evidence to traverse a rejection. Relevant here, patent applicants can submit a Rule 132 declaration to rebut an examiner’s obviousness determination. One way to do this is to present “secondary” or “objective considerations of non-obviousness,” such as a long-felt but unmet need or evidence of commercial success. A similar way to rebut an obviousness rejection with a Rule 132 declaration is to find some well-respected expert to tell the examiner how the invention is the bees knees.

Rather than get a Rule 132 declaration, however, the applicants filed an RCE and tried to circumvent Berman and Rush with a claim amendment:

But our examiner held firm. In a May 2013 non-final rejection, she noted that Rush taught that patients that failed to respond to adequate treatment with two antidepressants were deemed as having clinically significant TRD.

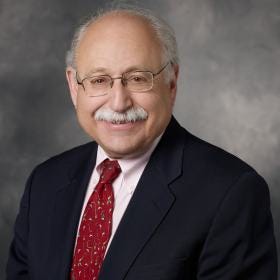

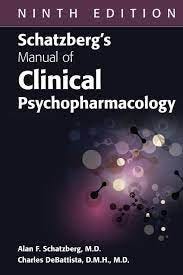

Enter this guy:

Schatzberg is one of the world’s premier experts on clinical pharmacology. He has a gold plated resume, decades of experience as a researcher and clinician, and maybe has won almost every relevant award in the field. He wrote the manual on clinical pharmacology. Literally.

In a Rule 132 submission, Shatzberg testified that he had no financial or business interest in any of the institutions filing for the patent, but was compensated at his standard rate. Then, he explained, a person of skill in the art in March 2006:

Would not have thought that there was a reasonable chance of success in treating those suffering from TRD with ketamine.

Would have found it surprising and unexpected that a single dose of ketamine could alleviate TRD within 2 hours.

Would not have combined Berman, Rush, and Mermelstein in the manner proposed by the examiner.

Would not have read Berman and Rush in the same way the examiner did.

Schatzberg also declared:

[I]t is my personal experience, based on over 30 years of treating patients with depression, that in 2006 (and continuing through today) it was very difficult, if not impossible, to predict that a given drug was reasonably likely to be successful in treating TRD in a given patient. In my experience, patients suffering from depression who have failed two adequate antidepressant treatment are extremely refractory to treatment. I estimate the chance of successfully treating such patients to be less than one-in-five.

The word of Schatzberg sealed the deal. In March 2014—eight years from the provisional filing—the PTO issued a Notice of Allowance with a claim amendment as follows:

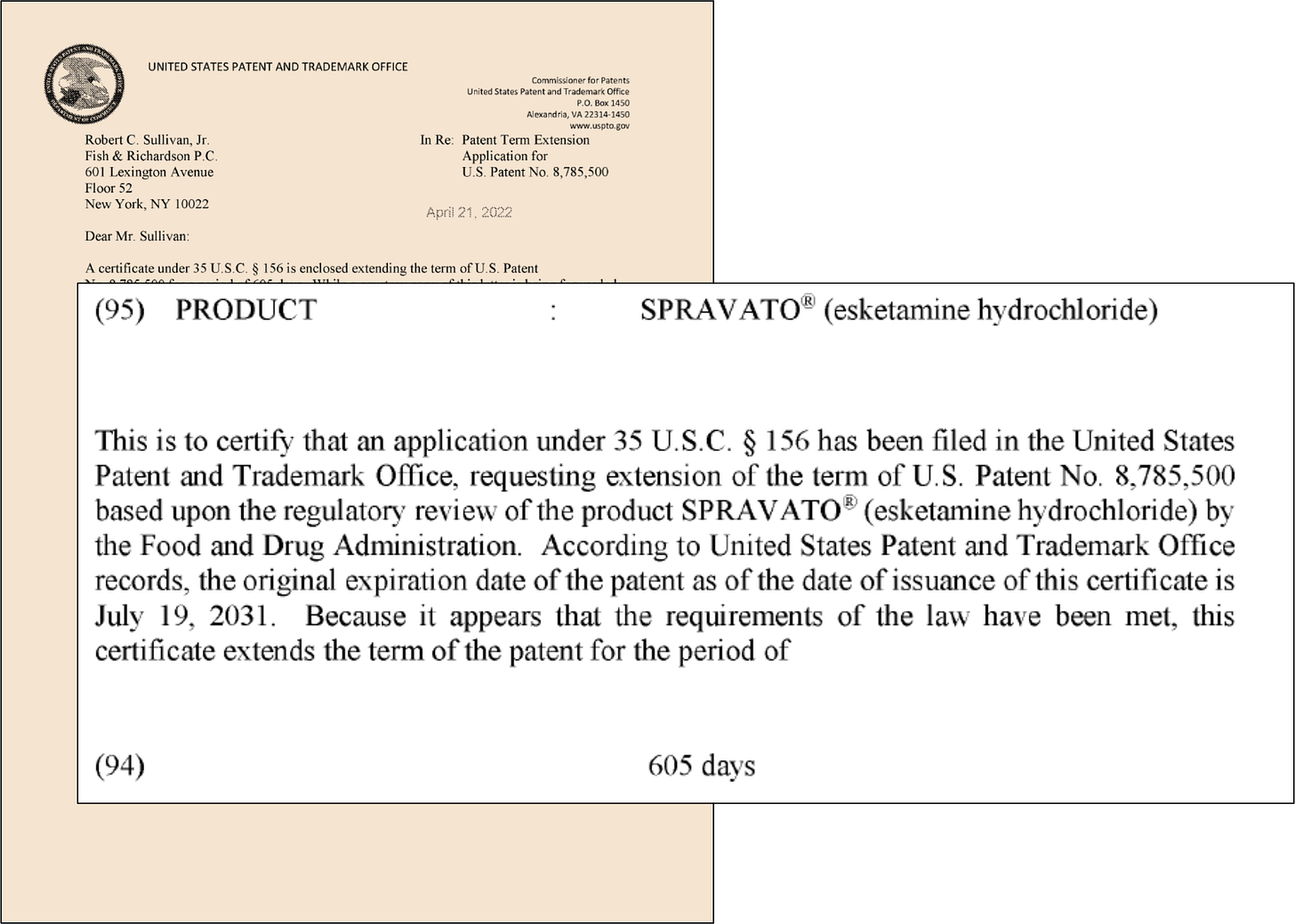

Three months after that, the applicants paid the issue fee. And on July 2, 2014, the patent issues as U.S. Patent No. 8,785,500 with a “Patent Term Adjustment” (PTA) of 1275 days. A what?

A PTA is a process of extending the life of a patent to accommodate for delays caused by the PTO during prosecution. A PTA is added on top of the lifespan of a patent—which is usually 20 years from the earliest application to which priority is claimed. Many issued patents have some form of PTA.

In the case of the U.S. Patent No. 8,785,500, the PTO calculated almost 3.5 years of delay.

Patent Families

Here’s the thing about patents. They spawn. Asexually.

Patent law permits inventors to file for subsequent or “child applications” that descend from a parent while a patent is being prosecuted. These subsequent applications are called “continuation” and “divisional” applications:

A continuation application is a descendent application that has the same subject matter as the claims of the parent application.

A divisional application is a sibling application that splits from a parent when the parent receives a restriction requirement by the examiner during prosecution because the application contained more than one distinct invention.

Children applications must be filed while a parent patent application is pending. Importantly, as long as the parent specification fully supports the claims of the child, children get the benefit of a parent’s priority date. Take, for example, a second generation (continuation) in the Intranasal Ketamine Patent family, U.S. Patent No. 9,592,207:

This is how multi-generation patent families are spawned. In patent world, it is normal to keep filing for additional claims with continuation applications. And continuations on continuations. This can continue for the entire term of a patent, with each continuation getting the benefit of the earliest priority date. One specification can generate dozens of patents with different patent claims.

It is also normal to have a continuation strategy. A company may, for example, wait for other companies to bring competing products to market and then try write claims to cover those products. A parent patent could disclose different formulations of a compound, but claim only one of them. If a competitor later releases a competing formulation, the inventor could, using a continuation patent, grab a new set of claims and try to ensnare covering the competing product with patent rights. This is true even though the competing product predated the filing of that continuation. Totally kosher.

In sum, one can do many things with continuation/divisional applications, including:

Broader or narrower claims. Sometimes the examiner only allows a narrow claim. Filing a continuation patent allows the inventor to pursue broader claims with “narrow” coverage. You may even get a different examiner on a continuation more prone to issue patents.

Claim a competitor’s product. A competitor product that predates a claim will normally anticipate the claim and render it invalid. It is therefore impossible to accuse a competitor’s product of infringing a patent if that product predates a patent’s priority date. But since continuation patents descend from a parent and inherit an earlier priority date, it is possible to draft claims that inherit an earlier priority date but cover a competitor’s products, so long as (1) the claim is supported by the earlier filed specification and (2) the competitor’s product was released after the priority date.

Keep pace with the art. Some arts progress at a rapid pace. Continuation patents allow inventors to continue to write claims based on an earlier specification to keep pace with an evolving art.

Strategic value. Continuation applications can be tools in patent enforcement or contemplated patent litigation. For example, an open continuation application allows the inventor to draft a new set of claims that can avoid newly discovered prior art that might invalidate a set of patents. Having an “open” family and a threat of writing claims to cover a competitor’s product can also act as a litigation deterrent. Thus, continuations have offensive and defensive value.

The ability of patents to spawn children is perhaps another reason to be skeptical of the cost-effectiveness of Freedom to Operate’s strategy to invalidate some of the Compass patents. While I think FTO could be a conceptually worthwhile endeavor, I’ve likewise gone on (LinkedIn) record agreeing with Graham Pechenik’s take that the PTAB denying institution was a complete win for Compass.

The other point to note is that Compass has continuations “open” on the family—so even one did cut a snake off Medusa’s head, more can (will?) spawn to take its place:4

And there is nothing nefarious about this. That is just how patent law works. Don't hate the players, hate the game.

One More Thing…

Passed as part of the Hatch-Waxman Act, 35 U.S.C. § 156, permits a patent owner to apply for a “Patent Term Extension” (PTE) and restore time on one patent that was effectively lost due to pre-market approval requirements. A maximum of 5 years can be added back to patent life in this manner. The total life for the product with the PTE cannot exceed 14 years from the product's approval date.

To be eligible for a PTE based on FDA approval, at least one patent claim must cover an approved drug product and:

The patent has not expired;

The patent term has not been extended previously;

The patent owner submits a complete and timely PTE application;

The product has been subjected to a regulatory review period; and

The permission for the marketing or use is the first permitted.

In the case of the Intranasal Ketamine Patents, it turns out, in 2022—years after issuance—two received PTEs because claims covered the FDA-approved Spravato®, extending these patents all the way out to 2034.

Now, maybe you are thinking what I’m thinking. Spravato® isn’t ketamine; it is esketamine hydrochloride. And Spravato® isn’t a product sold by Yale; it is sold by Janssen Pharmaceuticals…

In Part 2, we’ll do a little stereochemistry and more patent law to maybe answer this question—and others.

Until then, just chill, ’till the next episode.

Few individuals have contributed more to the science of the NMDA system in depression/anxiety than Phil Skolnick.

There are alternatives to a RCE as well, such as an Amendment After Final Rejection (AAF) or taking an appeal to the Patent Trial and Appeals Board (PTAB).

In a prior installment, I referred to references by the last name of the first listed inventor. As the image shows, this is how patent people speak about prior art.

Full disclosure: Despite their notoriety, I haven’t studied the family carefully, so I’m not commenting one way or the other on their merits.

Thank you again for the clear and intriguing insights!