Hot Psilocybin Patent Garbage

How to invalidate a psyschedelic patent in 30 minutes on a Sunday afternoon.

From the patent on using LSD to treat food allergies to Compass’s attempt to patent psilocybin use and “soft furniture,” last week’s publication of the patent application entitled “Treatment of Anxiety and Depression” or the “NYU Application” officially marks a new race to the psychedelic patent bottom.

Introduction

The NYU Application is assigned to Reset Pharma, “a well-capitalized highly experienced biotech team to develop and commercialize innovative and highly effective therapies for demoralization, anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer and other illnesses.” Here is Claim 1 of the NYU Application:

Boiled down, the claim covers a method for “alleviating” depression or anxiety in a cancer patient for more than a year by giving them one—and only one—dose of psilocybin. That’s it. The NYU Application has a “priority date” of November 2020, i.e., the earliest date the application can claim precedence over other prior art.

Despite its breadth, the claim is poorly worded for at least two reasons.

It isn’t clear to me what “alleviating” depression means. That term might be indefinite and therefore invalid if it does not inform a person of skill in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty.

As written, the claim is easy to operate around. Because the claim covers administering a single dose and “no further dose” for at least one year, administer two doses and you are in the clear. The doses could be administered days apart. Maybe even the next day. And maybe, the second dose could be non-psychoactive.

But set those issues aside. Did NYU and Reset Pharma really submit an application to patent giving dying cancer patients one dose of psilocybin to treat anxiety … in November 2020? Yes. Yes, they did.

But don’t worry. Matt Zorn, J.D. is assigned to this case. Most of you know me as that lawyer who goes around the federal court horn with Shane suing DEA. But controlled substances is my side hustle. When I’m not arguing appeals against DEA, I’m a pretty good commercial trial lawyer that specializes in complex messy litigation, and specifically, patent litigation. I also clerked on one of the busiest patent dockets in the nation.

Put simply, I know my way around a patent. I’m also good at sniffing out BS and am exceptional at finding where the bodies are buried. For example, I’m the “anonymous source,” referenced in this 2015 ABA article that went down to the Library of Congress in 2012 to take a picture of the copyright records to prove that the 10th edition of the Bluebook had fallen into the public domain because the copyright on the pre-1963 publication hadn’t been renewed under an arcane exception to U.S. copyright law.1

Fortunately, our case today does not require travel. In fact, writing this article up aside, it took me little more than 30 minutes of sleuthing on Public PAIR and the internet to bust open this dumpster fire.

Friends, sharpen your pencils and strap yourselves in. This is a longer piece, a bit technical, and a better read on a computer screen. But if you stick it out, I promise it is worth it.

A Patent Primer

A tutorial on patent law is beyond the scope of this essay. But for those who don’t know their way around a patent, here’s a brief review of the relevant concepts.

Patent Claim. A patent claim defines the metes and bounds of a patented invention. Claims define the scope of legal protection. They follow the patent specification. To infringe a patent, the accused product or method must meet every element of a claim.

Patent Specification. The specification or written description is the main text. It describes the invention and provides support for the claims. This specification or written description is the bulk of a patent document and precedes the claims. It usually contains words, but it may also contain pictures, figures, diagrams, and tables. The written description must show a person of skill in the art that the inventors had possession of the claimed invention on the filing date and provide enough detail to enable the person of skill in the art to make and use the invention.

Prior Art. Prior art is generally defined as anything available or disclosed to the public that might be relevant to a patent claim before the effective filing date of a patent application. For patent filings after March 2013, prior art is defined by 35 U.S.C. § 102:

(1) the claimed invention was patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention; or

(2) the claimed invention was described in a patent issued under section 151, or in an application for patent published or deemed published under section 122(b), in which the patent or application, as the case may be, names another inventor and was effectively filed before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.

Novelty and Non-Obviousness. To obtain a patent, an inventor must claim something that is both new and non-obvious. To be new, a patent claim cannot be already disclosed in a single prior art disclosure or reference. When a patent claim is disclosed in a single prior art reference either expressly or inherently, it is said to be “anticipated.” A patent claim is also invalid as obvious if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious to a person of skill in the art before the effective filing date of the claimed invention. A patent can be rejected or invalid as obvious based on one or more prior art references.

Duty of Candor. Each individual associated with the filing and prosecution of a patent application has a duty of candor and good faith in dealing with the Patent Office, which includes a duty to disclose all information known to that individual to be “material to patentability.” Importantly, this duty encompasses more than merely disclosing prior art. Rather, under 37 C.F.R. § 1.56, the duty requires patentees disclose all information that is “not cumulative to information already of record or being made of record in the application” and either (1) establishes, by itself or in combination with other information, a case that a claim is obvious or not new or (2) refutes or is inconsistent with a position the applicant takes in asserting patentability.

The duty to disclose all information known to be material to patentability is satisfied if all information known to be material to patentability of any claim issued in a patent is cited or submitted to the Patent Office in the manner prescribed by §§ 37 C.F.R. §§ 1.97(b)-(d) and 1.98. Every named inventor, attorney prosecuting an application, and every other person substantively involved in the preparation or prosecution of the application and is associated with the inventor, the applicant, an assignee, or anyone to whom there is an obligation to assign the application owes a duty of candor to the Patent Office.

Phew. Now, let’s get to the good stuff.

The NYU Application

NYU filed a provisional patent application on November 16, 2020. Generally speaking, a provisional application is a placeholder that gives the patent applicant 12 months from the date the provisional application filing to refine the invention while allowing the applicant (here NYU) to maintain the provisional filing date as the priority date.

Sometime after that provisional filing, NYU licensed the patent to Reset Pharma (and its management team and three boards: the scientific advisory board, board of directors, and strategic advisory board). Reset entered into “an exclusive license from NYU Langone Health for intellectual property (IP) associated with the use of psilocybin and related psychedelics for the treatment of mental illness in patients with life-threatening diseases, including cancer.” The company then made Stephen Ross, M.D., the doctor who appears to have led the psilocybin studies at NYU, the chair of its Scientific Advisory Board.

So far, so good.

The specification of the NYU Application begins with background to the invention. This is normal. The background acknowledges that the NYU Application isn’t the first publication to disclose the use of psilocybin to treat anxiety in advanced stage cancer patients. Three other studies came before it and are listed on the face of the patent. In particular, pay attention to a 2016 study that names Ross S et al. as the lead author. We’re going to call this one “2016 Ross.” You can read it here. It is going to be very important.

Given that the patent acknowledges at least three well-known other prior art studies that specifically looked at single-dose administration psilocybin in end-stage cancer patients for depression/anxiety, what could possibly be new, non-obvious, and patentable about Claim 1 of the NYU Application? The patent’s answer is in the next paragraph after the disclosure of these three studies. “[D]espite the promising evidence regarding the acute therapeutic effects of psilocybin, there is little data suggesting safety and efficacy of these interventions in the long term.” Thus, the inventors allegedly discovered that single administration of a psilocin prodrug can achieve “sustained relief from cancer-related psychiatric distress.” “Advantageously, only a single dose is required which means that it is not necessary for the cancer patient to further complicate the pharmaceutical treatment regimen for their cancer.”

In other words, the prior art may disclose (a) one dose of psilocybin providing symptom relief for less than a year or (b) more than one dose for symptom relief for more than a year. But the inventors claim that until 2020, nobody had figured out administering a single dose of psilocybin could “alleviate” anxiety or depression symptoms in cancer patients for “at least one year.” As a result, a method to administer a single dose—and only a single dose—of psilocybin to provide relief from anxiety and depression past a year is claimed. The specification goes on to claim entitlement to all prodrugs of psilocin, including natural sources of such as mushrooms, and for all forms of cancer.

2020 Ross

Time to return to 2016 Ross. It turns out, Stephen Ross, his co-inventor Gabrielle I Agin-Liebes, and the other authors of 2016 Ross published a follow up paper to 2016 Ross on January 9, 2020. The follow-up article is entitled “Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer.” Let’s call this reference “2020 Ross.” It is very important too.

Consistent with the duty to disclose, the applicants disclosed 2020 Ross to the examiner. Unlike the 2011 Grob study, the 2016 Griffiths study, and 2016 Ross, however, 2020 Ross is not discussed in the specification. Nor is it listed as one of 19 references listed at the end of the NYU Application specification.

Instead, a citation to 2020 Ross is buried in the third of three separate information disclosure statement (IDS) filed with the Patent Office under §§ 37 C.F.R. §§ 1.97 and 1.98 as Non-Patent Literature disclosure number 20 amidst a soup of other references.

In these IDS filings, 2020 Ross is disclosed alongside about 200 other references comprising 150 foreign patent publications, 15 U.S. Patents, 13 U.S. patent applications publications, and 26 non-patent documents that are shuffled in non-alphabetic, non-chronological order. We’ll see why this is problematic in just a moment. For now, recall that ordinarily, these IDS filings suffice to meet one’s duty of candor. After all, the reference is disclosed to the examiner. There is no failure to disclose.

Even so, many might frown on disclosing an important reference like 2020 Ross on the last pages of an IDS among many other less important references. Some call this prosecution strategy “burying.” A patent prosecutor has a duty to disclose all material information. Not only that, but the patent examiner is presumed to have read everything put in front of her, which in this case, is all 200+ references. “Burying” important material information is a way to comply with the duty and hope that material information gets lost in a pile of other less material information—often junk. Increase the noise-to-signal ratio. Not surprisingly, this often works. Importantly, burying isn’t always nefarious. Sometimes, there is a lot of relevant prior art. Indeed, that could be the case here.

Meet the new Ross… Same as the old Ross

Unlike 2016 Ross, the 2020 Ross article isn’t one you can read. You can get the abstract on PubMed, but the full-text is hidden behind a paywall.

Fortunately, a number of generous people subscribe to this newsletter. And using that subscription money, for the steep price of $44, I got a fresh full-text PDF copy of 2020 Ross. (You subscribe don’t you?!)

2020 Ross … let’s just say it is a barn-burner. Bottom line: the NYU Application is a copy/paste job of 2020 Ross. Start with Lines 11 through 16 of NYU Application, the “Background of the Invention”:

Now, the Introduction to 2020 Ross:

Look familiar? This is not isolated plagiarism. Whole swaths of 2020 Ross are copied, down to exact syntax and punctuation.

Compare (NYU Application):

With (2020 Ross):

And (NYU Application):

With (2020 Ross):

I could go on. Past typical boilerplate patent mumbo jumbo, little in the NYU Application is original. The entire “Outcome measures” section, for example, is copied almost verbatim from 2020 Ross. Same with the “Data analysis” section. Of course, looking at the NYU Application and how 2020 Ross was disclosed but not cited, you’d never know this to be the case.

As disturbing as this prolific copy-and-paste job is, that isn’t what troubles me most. What troubles me is where the two documents differ. Certain edits or tweaks to the NYU Application appear to conceal the connection between the 2016 “parent” study (2016 Ross, which is prior art) and the alleged invention shown in the NYU Application.

The text highlighted in red below is text from the NYU Application that does not appear in 2020 Ross. Highlighted in yellow, is text is text copied from 2020 Ross. Note how the red highlighted text describes the study being done and what it does not say: it omits the material fact that what was being done was, in fact, the same protocol and patients in the 2016 study as disclosed in 2016 Ross.

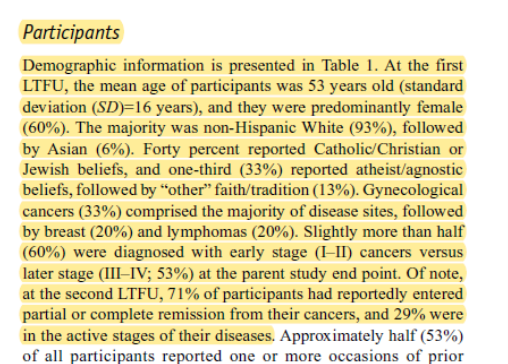

There can be no doubt that the NYU Application is describing a follow-up to 2016 Ross, as 2020 Ross makes clear. Noting that 2016 study is the “parent study,” 2020 Ross discloses that the participants in the 2020 study are a subset of the same participants in the 2016 study.

Let’s look at 2020 Ross:

Of course, from my review, “parent study” never makes it into the NYU Application specification. And when you really look at 2020 Ross and the NYU Application side-by-side, it is hard to believe that these edits are accidental. Take, for example, how the words “In the parent study” mysteriously drop out of the NYU Application when the sentence from 2020 Ross is ported over.2

But let’s say, for whatever reason, you still aren’t convinced 2020 Ross and 2016 Ross are the same clinical trial. Look no further than the clinicaltrials.gov, which shows that 2020 Ross and 2016 Ross refer to the exact same clinical trial.

The connection among all these is not a minor oversight. It is a really important fact. Once one appreciates the connection among 2016 Ross, 2020 Ross, and the NYU Application—that all three describe the exact same clinical trial—the language the patent specification uses to describe 2016 Ross as if it were a different study (“In that study…”) seems a bit misleading:

Current Claim 1 is Invalid Because of 2016 Ross

Without seeing more, to me, this looks like an attempted snooker under the nose of a busy patent examiner. Or, as we say in the patent world, attempted inequitable conduct—the “atomic bomb” of patent law. As discussed above, patent attorneys and inventors have a duty to of candor to disclose all information material to patentability. But when a patent attorney or inventor intentionally withholds “but-for” material information from the Patent Office from the examiner, the resulting patent is unenforceable. That means you have to show that the Patent Office would not have allowed a claim had it been aware of the undisclosed prior art.

Proving this type of fraud on the Patent Office is exceptionally difficult. Absent direct evidence of fraud, a specific intent to deceive the examiner has to be the single most reasonable inference from the facts. And here, I suppose it is possible that there has been a mix-up or a staffing change between filing the provisional and non-provisional application. More important, there isn’t anything being withheld. 2020 Ross is disclosed, albeit in a plagiarized and perhaps misleading way.

Nonetheless, a further investigation could be justified. That 2020 Ross is disclosed in an information disclosure soup is one thing. That the material information contained in 2020 Ross—that the entire disclosure that NYU Application is a follow-up to the previously disclosed 2016 study in 2016 Ross—is obfuscated and selectively omitted from the copy-paste job in the specification is wholly another.

Here is why this matters. Interestingly, because 2020 Ross was published less than one year before the effective filing date of the patent application, it may not itself be prior art under 35 U.S.C. 102(b), which offers inventors a one-year grace period between disclosing an invention and filing for a patent. But whether 2020 Ross is itself prior art is beside the point. The duty of candor encompasses disclosing all information “material to patentability.” Here, the material information that is omitted and/or buried is what 2020 Ross describes and what the NYU Application tactfully omits: 2020 Ross is connected to the 2016 study and 2016 Ross, and unlike 2020 Ross, 2016 Ross is definitely prior art that describes the same study as the NYU Application. And that connection should block the issuance of these claims because it shows the claims are neither new nor non-obvious in light of 2016 Ross.

This is a classic inherent anticipation. One cannot patent newly discovered properties of old items or methods. Anticipation “does not require that a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time would have recognized the inherent disclosure.” Schering Corp. v. Geneva Pharm., 339 F.3d 1373, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2003). “Where ... the result is a necessary consequence of what was deliberately intended, it is of no import that the article's authors did not appreciate the results.” MEHL/Biophile Int'l Corp. v. Milgraum, 192 F.3d 1362, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 1999). Inherent anticipation applies to “method” claims too. Bristol–Myers Squibb Co. v. Ben Venue Labs., Inc., 246 F.3d 1368, 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (explaining that newly discovered results of known processes are not patentable because those results are inherent in the known processes). In a sense, inherent anticipation follows from commonsense: you don’t get brand new methods on using known compositions if you conduct follow-ups every year and discover that a previously observed effect endured. Discovering new results from a known process doesn’t make a previously known process novel.

In this case, there is no dispute that the process of administering psilocybin to a cancer patient according to the exact same single-dose process was known before the effect filing date. It is disclosed in 2016 Ross. Improving depression and anxiety symptoms at the one-year mark is a necessary or inherent consequence of that original 2016 protocol. That NYU and Stephen Ross, et al., allegedly didn’t appreciate those results until 2020 is of no moment. Also, how much do you want to bet that the psilocybin “kit” disclosed in Claim 28 is the same kit used or disclosed in 2016 Ross?

These claims are clearly invalid.3 Moreover, despite the fact that 2020 Ross is disclosed, I believe that under the circumstances, a patent examiner might be justified in terminating prosecution on grounds of attempted inequitable conduct. In Apotex v. UCB, for example, the Federal Circuit held that the inventor and patent prosecutor had committed inequitable conduct by “affirmatively and knowingly misrepresent[ing] material facts regarding the prior art.” Again, I don’t know all the facts here, particularly on intent. But in my opinion, if affirmatively obfuscating the fact that the all of the data in the NYU Application comes from the same study conducted in 2016 Ross is not plausible affirmative egregious misconduct, it certainly comes close.

But Wait, There’s More

Remember the 19 references I said were listed at the end of the NYU Application:

And let’s compare it to the far more voluminous list at the end of 2020 Ross:

I want to focus on one particular reference disclosed in 2020 Ross but not in the NYU Application:

Let’s call this one 2017 Ross. While Agin-Leibes is a co-inventor and author of 2016 and 2020 Ross, Belser and Swift are new faces. But within the et al. of this citation of the 2017 publication, available here, is Stephen Ross.

In 2017 Ross, the researchers describe interviews 13 patients from the 2016 single-dose administration study. Eight were interviewed “at approximately 1-year follow-up” and many disclosed “lasting impacts to their quality of life.” Sounds like alleviated depression and/or anxiety to me. I may have missed it. But looking through the three IDS disclosures and 26 Non-Patent Literature references, among nearly 200 references disclosed, I didn’t see 2017 Ross—a one-year follow-up study of the same 2016 study participants and prior art published well before the effective filing date of the NYU Application.

2017 Ross also has a companion article entitled “Cancer at the Dinner Table: Experiences of Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy for the Treatment of Cancer-Related Distress.” Let’s call this 2017 Ross 2. It too discloses interviews “approximately 1 year following” the psilocybin dosing session. The article then goes on to discuss how in one patient the psilocybin experience left an “enduring impression” on one patient and has kept that feeling “ever since.” Another, who had described his anxiety as “crazy,” came to “not only accept the effects of cancer on his body but also a greater embracing of his remission.” And of course, in the results discussion, the authors go on to note how the interviews are consistent with “enduring positive changes” that go “beyond the mere reduction of symptoms.”

The 2017 Ross 2 article then discusses that the results showing “improvements in anxiety and depression” are “consistent with prior research on psilocybin with healthy normal volunteers that showed that similar positive attributes in meaning and spiritual significance were enduring at the 14-month follow-up,” connecting 2016 Ross and disclosing or rendering obvious the NYU Application.

Concluding Thoughts

Here is my take: the NYU Ross crew did one study in 2016 and repeatedly published follow-up studies. Now, years later, they are trying to put the toothpaste back in the tube and seeking to monetize the research by obtaining patent protection for a study that is already thoroughly disclosed in the prior art. Our patent laws say this is a no-go.

What do we do about this? As far is this application is concerned, here is one idea. Under 35 U.S.C. § 122(e), any third party can submit for consideration and inclusion a printed publication “of potential relevance to the examination of the application,” so long as the submission is made within 6 months after the application is first published. The NYU application was published last week. On Drugs is a reader supporting news outlet (subscribe!), and this article is a “printed publication” that is “of potential relevance to the examination of the application.”

You can do it. You’ve got six months. Just tell the patent examiner to look at the information from this newsletter:

Better yet, wouldn’t it be great if the entire community told the examiner? Rather than just moan about psychedelic patents and the patent system on Twitter, this time, you have the power to do something about it. I’m handing it to you on a silver platter:

Beyond this patent, more concerning is the chutzpah it takes to take philanthropy and file something like this. Why even try? Right now, I can only speculate. But I can think of two reasons.

First, someone thought it could slip by the examiner. After all, if someone got a patent on a DMT vape pen, why not try for single-use psilocybin + cancer? Even if there is even only a 1% chance you can get a patent like this, with little downside repercussions other than an application fee, why not try? Race to the bottom.

To be clear, not every attempt to obtain ridiculously broad claims encompassed by the prior art is improper. Patent attorneys often file for broad patent claims knowing they are likely to get rejected. Patent prosecution is a lot like a negotiation where the patent applicant wants claims as broad as possible without stepping on the prior art. By starting with broad claims, an applicant can try to get as broad coverage as possible by narrowing the claims during negotiations in view of the prior art.

But it is hard to see how that could apply here. As discussed above, the NYU Application discusses the exact same study as 2016 Ross. By all indications, the NYU Application is 2016 Ross. In that light, it is hard to see how any examiner could allow any claims supported by the specification—unless, of course, a busy patent examiner doesn’t get to or fully appreciate IDS Number 3, Non-Patent Literature Reference #20 and the connection among 2016 Ross, 2020 Ross, and the NYU Application.

A second explanation may be equally likely: money. Many psychedelic medicine shops are a dime a dozen these days, particularly variants on the MAPS/Usona/Compass concept in the psilocybin and MDMA realm. Some actually have really great novel ideas and/or are working on second-generation molecules. Others, however, are more of the me-too variety. In this crowded space, often the only thing that differentiates company A from company B is a better promise of future returns through patent filings. Not issued patents, but the promise of a patent with a provisional or non-provisional patent application. And in a cash-poor world where every company, researcher, and their brother is on the hunt for VC money and licensing deals, even filing for a patent can be a prudent move to make a company more attractive in raising capital from investors or partners.

Of course, if I were Reset Pharma or an investor in Reset Pharma (looking at you Palo Santo folk) and did the patent diligence, here is how much I would have recommended paying for this IP:

In fact, I might seriously consider abandoning this nonsense patent filing immediately. Never mind forever being labeled or associated with the company that tried taking the administration of psilocybin to terminal cancer patients private. Ditching this dumpster fire might be in your best interest anyway. If you think a good case of inequitable conduct or invalidity can be made out—and if I’m the attorney staring you down, count on it—then this patent’s value to your portfolio might be less than nil. Asserting a bogus patent in litigation is the surest way to pay an adversary’s attorney fees, which can be in the millions.

Epilogue

Around six months ago, I read a draft of an essay by I. Glenn Cohen and Mason Marks on psychedelic patents, which is now published in the Harvard Law Review. I had pointed criticisms for the authors that they graciously considered and addressed in the text.

Zooming out, I felt the essay oversold the danger of patents in the psychedelic space and went a bit too far with psychedelic exceptionalism. To some extent I still feel that way. But less so.

After spending a Sunday afternoon writing this essay, I gave the Cohen and Marks essay another shot. Not surprisingly, still, I disagree with more than a few things in it. But I’ve come around on some of its core ideas—or at least part of the way. For example, this paragraph is worth deeper consideration:

Asymmetries of power resulting from abuses of the patent system are particularly relevant to the emerging psychedelics industry, where barriers to entry are already high. The DEA classifies most psychedelics, except for ketamine, as Schedule I controlled substances, because it believes they have no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. The Schedule I status of psychedelics increases market uncertainty, scaring away risk-averse investors. Prohibition may also reinforce patent monopolies. However, the fruits of overseas research can still be patented in the United States. Therefore, current federal policies on psychedelics create obstacles to domestic researchers and companies, which can be overcome by firms that can afford to take their research and development overseas.

I would go one step farther. The draconian regulatory environment surrounding researching pharmaceuticals, especially psychedelics, might be a primary reason actors in the psychedelic space are trying to patent prior art or obvious variations of prior art. Established pharma companies have capital on-hand to do research without VC backing. But big pharma is not interested in doing early-stage research psychedelics. Among other reasons, the principles behind the current iterations of psychedelic medicine do not fit their current profitable business models. So, the research is left to start-ups, smaller entities, and psychedelic departments.

These smaller companies do not have bottomless pits of resources to crank out new molecules and do dozens of clinical trials like Big Pharma. That means (1) raising outside money and (2) using limited resources wisely by aiming at fewer “high percentage” targets, i.e., research and develop what already appears to be a good idea and supported by research. Therein lies the problem. When you do a “high-percentage” clinical study, you inherently develop something that is more difficult to patent, especially with the classical psychedelics. But without patents, it is difficult to raise outside money, whether venture money or philanthropy.

Solving this economic dilemma is a topic for another day and better brains. But here are a few preliminary thoughts.

With some a couple others, I’ve been trying to work up a private market solution that doesn’t require changing the world, but simple contract drafting: a standardized suite of FRAND patent licenses for psychedelics that anyone, including funders, can attach to equity investments and research projects to ensure that those projects don’t culminate in Hot Psilocybin Patent Garbage™ and gouging consumers. Feel free to drop me an e-mail if you are interested or know someone who wants to fund the project. It could actually make a difference. (As of publication: connecting domain name to website pending.)

A legislative idea would be to strengthen the medical practitioner immunity in 35 U.S.C. § 287(c) to bar method or process patents using known compositions of matter that are already off-patent. Maybe big pharma opposes, but perhaps there is a way to word a law that wouldn’t get too much opposition.

Alternatively, Congress may want to consider extending data exclusivity for Schedule I drugs or tax breaks for research with Schedule I drugs to incentivize such research and loosening some of the pressure of needing patent rights to do such research. I’d rather have psychedelics companies flipping tax credits over obtaining anticompetitive patents.

Another idea is conditioning government grants for Phase I and II clinical trials with no-patent or FRAND patent pledges. See bullet point 1.

Indeed, on the first bullet point, what really troubles me is that the 2016 NYU study appears to have been funded in large part by philanthropy from Heffter Research Institute, RiverStyx Foundation, and Bill Linton (of Usona). Even Carey Turnbull—yes, the same Carey Turnbull that founded a non-profit called Freedom to Operate dedicated to challenging “flawed psychedelic patent claims” such as the Compass patents—is a supporter, as 2020 Ross discloses.

This emphasizes the urgent need for the first bullet point—a standardized patent license that philanthropists, funds, and anyone can use to avoid Hot Psilocybin Patent Garbage™. This may be the beginning, not the end.

As someone who knows what it is like to lose someone to cancer, I’m fighting to remove regulatory barriers not so private companies can erect barriers made of patents covering stale ideas funded by philanthropy. And the fact that many well-respected people in this community (indeed, people I respect) are unknowingly connected to this Hot Psilocybin Patent Garbage™ angers me. And it should anger you too. If not, let me reframe the idea.

Remember how Pharma Bro exploited a completely legal process to obtain proprietary rights over a cheap, off-patent, 70-year-old, rarely used generic drug, jacked up its price, and duped his investors. Did this 30-something year old make you angry?

If he did,4 then attempting to patent a method of using psilocybin to treat dying cancer patients suffering with depression/anxiety should make you irate. At the end of the day, the fundamental underlying conduct isn’t that different. Both are gaming a system to get proprietary rights where there should be none.

And don’t try to sell me that this isn’t the same because NYU et al. are nothing like a so-called greedy 32 year-old Pharma Bro because they will pour money back into patients and R&D. Remember, Shkreli and his company said that too. He also said his company would protect individual patients with a co-pay assistance program and would just gouge insurance companies.

No, the only difference is he was a little too brazen and got called out.

Long story.

This table has been edited since the original date of publication to account for an inadvertent mistake in swapping the headers. Other typos have been similarly fixed.

I have other questions about this patent filing. For example, 2020 Ross has 10 authors. The patent filing, however, names just Ross and Agin-Leibes as inventors. Although who gets to be the author of a research paper and the inventorship of a patent are not always concomitant, the large disparity between the named inventors of the NYU Application and authors of the nearly identical 2020 Ross research paper raises significant questions.

It didn’t make me that mad. What Shkreli did is not uncommon in the pharmaceutical industry.

thank you for this very well written and insightful article!

ps can you clarify what actions (substeps - text example?) to take specifically (and can anyone do this or is it limited to US citizens?)