GHB, Orphans, and REMS: A Regulatory Love Story (Part 1)

With a Bunch of Meandering Footnotes

Interested in psychedelics, psychedelic regulation, and/or psychedelic patenting? Or, do you have a pharma fetish (like me)? Either way, pay attention to this one.1 I’m going deep.

Around a month ago, in the District of Delaware, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) filed an amicus brief in Jazz Pharmaceuticals v. Avadel CNS Pharmaceuticals. An amicus brief is a brief filed by a non-party amicus curiae or friend-of the-court. Amici (plural of amicus) usually file these briefs to provide the court information beyond the main briefs. Typically, amici participate because they care about the outcome of a case or issue.

Federal agencies do not frequently file amicus briefs. And when they do, they usually file amicus briefs in important cases in appeals courts, not trial courts. There is something very important going on in this case.

Fundamentally, Jazz is a pharma patent case. Jazz has a patent relating to its blockbuster drug Xyrem, i.e., branded sodium oxybate, i.e., the sodium salt of gamma hydroxybutyric acid, i.e, GHB. Avadel wants to bring a competing GHB product to market. Jazz sues Avadel. But as FTC’s participation suggests, this isn’t a run-of-the-mill pharma pissing match.

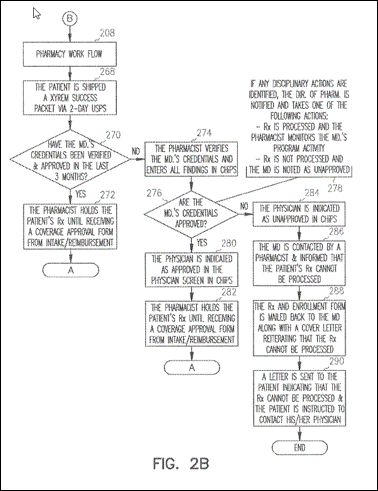

Sodium oxybate has been used to treat narcolepsy since the 1960s. Jazz’s drug, Xyrem, has been around since 2002. The patent at issue claims neither GHB nor a method-of-treatment (MOT) using GHB. Rather, Jazz’s asserted ’963 patent claims a system for distributing of sodium oxybate to be used in treatment. Specifically, it claims a computer-implemented system to address certain FDA-required Risk Evaluation Mitigation Strategies requirements of using Xyrem according to its approved labeling. The claim is long and gobbledygook. Boiled down, it recites checking a computer system to make sure a patient has a valid prescription.

In other words, Jazz has a patent on the REMS. And so, we’ll call the ’963 patent the REMS patent.

Jazz differs from a typical pharma slug fest in another way. Most pharma cases pit brand against generic. Not this one. Although the case involves the same statutory provisions that give rise to brand/generic disputes—the Hatch-Waxman Act—here, both Jazz and Avadel are brand. And both companies have patents.

The central issue in the FTC’s filing and the subject of this multi-part essay has to do with the Hatch-Waxman Act and something called the FDA Orange Book. When the FDA approved Xyrem, it approved Xyrem with a REMS requirement on distribution that coincided with a patent it had. Then, Jazz listed its REMS patent in the Orange Book. That’s the issue.

[Note: If you don’t understand some of the lingo, keep reading. I’ll define, describe, and explain as we move through.]

But before we get there, let’s take a step back. History and background is important. In Part 1, I will cover GHB and Xyrem history to give a fuller picture of how the dispute gets here and why it matters. Feel free to wait for Part 2 if this doesn’t interest you.

Part 1

GHB: A Brief History

GHB is an old drug with a familiar story.

Chemist Aleksandr Saytzeff reports the first synthesis of GHB in 1874. That makes GHB “older than aspirin.” The molecule is forgotten. In the 1960s, while searching for anesthetics, polymath Henry Laborit—a leading pharmacologist of the 20th century—rediscovers GHB. GHB was a logical candidate. It is an analogue of GABA, the body’s main inhibitory neurotransmitter. GABA antagonizes glutamate, the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the body. Other GABA-ergic substances include alcohol, benzodiazepines, and prescription sleep medications like Ambien.

GHB saw use as an anesthetic in the 1960s. But it wasn’t good, especially when compared to alternatives. GHB produces little analgesic effect. In doses necessary to produce anesthetic effects, research reported high incidents of myoclonic seizures and vomiting. GHB also depresses breathing.

In the 80s, users repurposed GHB as a sleep aid and bodybuilding supplement. Some research suggested GHB use could increase release of growth hormones and prolactin, promoting muscle building and sleep. Prolactin, released after orgasm2, has been tied to inducing REM sleep. Health food stores openly sold GHB as a “growth hormone stimulator.” Also, fun fact: John Stamos once got pulled over for using GHB to “lean out body mass.”

This era of (cheap) OTC sales ended, however, when FDA declared GHB unsafe and illicit in a November 1990 advisory. This advisory did not end GHB consumption, however. The 1990s saw users repurpose GHB as a club drug. Beyond the effects described above, at lower doses (20–30 mg/kg), GHB produces feelings of euphoria, relaxation, and sociability. GHB has also been linked to libido enhancement and “lowering of attractiveness standards for partner selection” (i.e., beer goggles).

Importantly, the 1990s also saw GHB repurposed as a date rape drug. GHB typically manifests itself as a colorless, tasteless liquid. That makes it easy to drop into a drink. DEA reported at least 58 deaths and thousands of recorded overdoses from 1990 to 2000.

Just like alcohol, GHB is dangerous in high doses. No surprise there. Both drugs (yes alcohol is a drug) are GABAergic. Thus, GHB doses > 60 mg/kg doses can cause coma, convulsions, and respiratory depression. Death is possible. The combination of GHB with alcohol potentiates these dangerous effects and produces more danger.

The main difference between GHB and alcohol, in my view, is that GHB is more dose sensitive there and so there is less margin for error with GHB. This study by Griffiths and Johnson comparing alcohol and GHB identifies other differences. It concludes the two are similar: “Within-session measures of abuse liability were similar between the two drugs.” But “post-session measures of abuse liability, including a direct preference test between the highest tolerated doses of each drug, suggested somewhat greater abuse liability for GHB, due most likely to the delayed aversive ethanol effects (e.g., headache).” Put another way, GHB has greater abuse liability…because it doesn’t cause hangovers?3 Indeed, given a choice, 7 of 11 participants chose to receive the highest tolerated dose of GHB over ethanol.

GHB research continues. Multiple studies—including clinical studies—have shown GHB to be useful in treating alcohol addiction. This is notable because, at present, treatments for alcohol addiction suck. Indeed, GHB administration is an approved therapy for alcoholism in Italy, not unlike the use of methadone in heroin addicts to block opiate cravings.

OOPD Asks Orphan Medical to Develop GHB As An Orphan Drug

Tucked in the bottom left corner of FDA’s bureaucracy is an office called OOPD or the “Office of Orphan Drug Development.” It is one of five departments within OCPP.

OOPD is the product of the Orphan Drug Act of 1983, a law Congress enacted to spur development into drugs that treat rare diseases or conditions. Essentially, the law addresses a market failure. Clinical trials are expensive. Developing drugs with small patient customer bases doesn’t pay. The Orphan Drug program sweetens the pot by giving drug developers an array of additional incentives to develop drugs for rare diseases, including tax credits, waived user fees, and 7 years of marketing exclusivity. And if the rare disease is pediatric? A nine-figure fast-track tradeable priority review voucher. Importantly, Orphan Drug exclusivity is full market exclusivity. This differs from New Chemical Entity exclusivity, which only prevents “me too” generic approvals for a shorter period.

As originally passed, the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 included an exclusion. Exclusivity only applied to a drug “for which a United States Letter of Patent may not be issued.” But shortly after enactment, Congress struck the patented drug exclusion. The House Report accompanying the 1985 Amendments explains that the Orphan Drug program experienced early successes because “many of the currently designated drugs were known by scientists and pharmaceutical researchers as having some potential in humans.” But by 1985, per FDA, most known orphan drugs were being tested and discovery of new drugs would require a “larger commitment of resources.” A product patent, the report says, may not provide a drug developer enough years of marketing exclusivity to incentivize investment and recoup development costs.

Patents generally have 20-year terms. So, the length of exclusivity for an Orphan Drug depends on when in the term the use of a drug for a rare disease is discovered, the subsequent development process, and when FDA approval is obtained. If this all happens late in the patent term, the patent may provide little to no exclusivity.4 And in that case, companies with expiring patent protection would have reason to delay orphan drug development:

To create an incentive under current law for the development of drugs with little patent term outstanding, the FDA is put in the position of having to delay approval until patent expiration so that the seven year period will apply. Otherwise, the FDA must use federal grant funds to conduct the necessary research since no company will sponsor the testing of the drugs.5

Of course, like other legislation discussed here (ahem Controlled Substances Act), over the years the Orphan Drug program has strayed from its roots—and is often abused. Consider “partial orphan” drugs: drugs approved to treat both rare and common diseases. One recent study found that of the fifteen top-selling partial orphan drugs, 21.4 percent of spending was assigned to orphan indications, 70.7 percent to non-orphan indications, and 7.9 percent to neither. Next, consider Humira—the best-selling prescription drug in the world and likely all-time: $200+ billion in sales. Did you know FDA also designated Humira an Orphan Drug? Not one or twice. Eight times. Congress noted this over a year ago:

The report also describes a Orphan Drug practice known as “salami slicing,” which is when drug companies file for separate, spaced out market approvals for disease subpopulations to extend exclusivity protections beyond the seven-year period:6

But I digress. (Or do I? I’ll come back to all this rambling.) Particularly relevant here, shortly after Congress passed the Orphan Drug Act of 1983, FDA designated GHB as an orphan drug for narcolepsy. GHB was one of the “known” orphan compounds. According to this term paper, Dr. Martin Scharf had filed for and received a treatment Investigational New Drug Application (IND) in 1983. Scharf conducted open-label trials with the drug. But he could not take the drug through the expensive clinical trial process. So, he began working with a generic drug company, which was acquired by Teva pharmaceuticals. Teva lost interest in the drug.

Enter OOPD. Three years following FDA taking GHB off-the-market, OOPD approaches Orphan Medical to develop GHB as an orphan drug for narcolepsy. No other company wanted to develop the drug. Scharf gave Orphan Medical his data, and Orphan got its own treatment IND to study of GHB in treating patients with narcolepsy and cataplexy. After clinical trials, the drug was on the verge of approval when…

The FDA Orange Book

Okay, before I get to that, let me digress again and introduce to the narrative another key legal player from the 1980s:

To balance the competing interests of pharmaceutical innovation and competition, Congress enacted the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known today as the Hatch-Waxman Act. This seminal law amended patent and drug law to both allow pharmaceutical development and encourage the marketing of generics.

Relevant here is FDA’s Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations or the Orange Book. The Orange Book is a list of approved drug products that FDA is required under the Hatch-Waxman Act to make publicly available. New Drug Applications (NDAs) to FDA require submission of certain patent information, which the FDA then lists in the Orange Book. Manufacturers are not supposed to list every patent related to an NDA. They should only list patents that claim either (1) a drug or (2) a method of using a drug (i.e., a MOT patent). That said, whether to list a patent is based on the decision of the manufacturer; the FDA does not police or determine whether particular patents should be listed in the Orange Book.

Listing a patent in the Orange Book gives the brand manufacturer a special legal privilege under the Hatch-Waxman framework: a regulatory stay. Generic manufacturers wanting to bring generics to market must certify in an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) that each Orange Book patent covering a listed drug has expired or will expire before the generic drug is marketed. Alternatively, it may certify a listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic drug. This second certification is called a Paragraph IV certification.

When a generic manufacturer submits a Paragraph IV certification, it must also notify the NDA holder and all patent owners. If the brand manufacturer/patent holder sues the generic manufacturer within 45-days of receiving that Paragraph IV notice, the NDA holder is automatically entitled to impose a 30-month stay of regulatory approval of the ANDA. This stay is intended to give the brand and generic the necessary time to resolve the patent litigation.

The important takeaway here is (1) the Hatch-Waxman scheme incentivizes listing patents in the Orange Book and (2) it incentivizes companies to sue on those patents—even where an infringement claim or the validity of the asserted patents may be dubious—and sort out the details later. In pharma, the economic benefits of a 30-month regulatory stay can be tremendous even if a lawsuit is destined to fail.

Regulatory Clampdown, Bifurcated Scheduling

Fifteen year old freshman Samantha Reid sipped on her Mountain Dew at a party. Little did she know, 17-year old Joshua Cole had slipped something in her drink to make the party more “lively.” The drug was tasteless. Neither knew the cocktail Cole had made was lethal. Reid died.

DEA first considered scheduling GHB in the mid-1990s after law enforcement data showed it to be an increasingly abused drug. But it was not until Reid’s death, along with the death of Hillory Farias years earlier that action followed—from Congress—led by representatives of the states in which the girls had died: Fred Upton of Michigan and Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas. And, as is often the case in drug law, when heading down sensational winds, Congress acted quickly.

In March 1999, Congress held a hearing entitled “Date Rape Drugs” to address the proliferation of GHB and two other drugs: Rohypnol and ketamine. By February 2000, Congress enacted the Hillory J. Farias and Samantha Reid Date-Rape Drug Prohibition Act of 1999 banning GHB. The House Report provides more detail, if you are interested.

Banning GHB outright by placing it alongside other highly dangerous drugs like marijuana in Schedule I would have been easy. But as the subtitle above notes, this drug scheduling had a hitch: Orphan Medical, stewarded by FDA, was in the final throes of bringing GHB to market as an orphan drug. So, the law directed DEA to place GHB into Schedule I on an emergency basis. But it contained an exception for GHB that “is contained in a drug product for which an application is approved under section 505 of the FDCA.” In that case, Congress ordered DEA to place FDA-approved products in the same schedule as that recommended by HHS for authorized formulations of the drug.

By the time Congress enacted the law, HHS had already provided its scheduling recommendation. The letter recommended that GHB be placed into Schedule I, except that GHB substances and products subject to IND applications should be placed into Schedule III. The letter explains, that GHB (1) has “a high potential for abuse relative to substances controlled in Schedules III, IV, and V,” (2) has “no accepted medical use,” and (3) when manufactured clandestinely, “is unsafe for use under medical supervision.”

One part of the HHS letter is worth quoting in full:7

Formulations of GHB currently are being studied under FDA-authorized INDs. At least one sponsor’s formulation has been granted orphan drug status under Section 526 of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, and is available under a treatment use protocol under 21 CFR § 312.34. None of the reports of actual abuse of GHB that support the Schedule I recommendation have involved GHB that was diverted from an authorized study. Moreover, given the ease with which GHB can be synthesized from readily available materials, it is unlikely that authorized studies will become a source for abuse.

Rather, the abuse potential of GHB, when used under an authorized research protocol, is consistent with substances typically controlled under Schedule IV. Information on the dependence-producing effects of GHB is limited, but available data suggest that its potential for physical and psychological dependence is also consistent with control under Schedule IV. Authorized formulations of GHB, however, do not meet the ‘‘accepted medical use’’ criteria set forth in Schedule IV. An authorized formulation of GHB is far enough along in the development process to meet the standard under Schedule II of a drug or substance having a ‘‘currently accepted medical use with severe restrictions.’’ Under these circumstances, HHS recommends placing authorized formulations of GHB in Schedule III.

Xyrem’s Risk Management Program

Less than two years after Congress took the dangerous date-rape drug off the market, GHB re-entered in 2002 as the FDA approved formulation Xyrem. And according to the recently enacted law, it entered Schedule III.

Because Xyrem was a notoriously dangerous drug, FDA expressly conditioned approval on specific restrictions on distribution and use under a precursor to REMS called the “Risk Management Program” beyond CSA controls. As discussed elsewhere, today, FDA can approve drugs contingent on specific restrictions on distribution according to a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies or REMS program. For example, as part of the REMS program, FDA can require a drug manufacturer to provide certain information to patients and health care providers.

In the case of Xyrem, FDA held a meeting with Orphan at the Holiday Inn in Bethesda, MD in June 2001 to discuss the safety/efficacy of Xyrem and risk management issues. Before the meeting, Orphan submitted to FDA a slate of materials, including written materials and an informational video with awesome cheesy 90s synth music.

In the briefing materials, Orphan laid out a proposed risk management program:

We believe that the precautions included in the Company's post-marketing program will constrain in every way possible the risks associated with this medicine while allowing its use by patients to meet their medical needs. These precautions include mechanisms to educate physicians and patients about the proper use of Xyrem, the unique implications of the bifurcated schedule, as well as closed-loop prescription and distribution systems to restrict the opportunity for diversion or misuse

Notably, the original risk management plan contained a requirement that the drug be dispensed only from a single, central pharmacy. According to this term paper, Orphan “designed the most centralized prescription drug distribution system in the country, largely on its own initiative” and used it to institute restrictions on distribution that were unprecedented in the industry. Indeed, the Orphan briefing shows the company advocating for the bifurcated HHS proposal and placement of its drug in Schedule III so that the company could provide tighter controls than would otherwise be available with a Schedule II designation:

As part of its risk management program, Orphan also noted it only sought approval for use in a small patient population and would be marketed “only for the approved label claim.” (Just a few years later, Orphan pleaded guilty to felony misbranding for marketing for unapproved indications.)

FDA approved Orphan’s centralized distribution plan, believing it to be an acceptable way to effectuate restrictions on distribution necessary for safe use of the drug.

Jazz Acquires Orphan; Engineers Billion Dollar Blockbuster

New player: Jazz Pharmaceuticals (NASDAQ: JAZZ). Jazz had little to do with the clinical development of Xyrem. The company launched in 2003, after FDA had already approved the drug. But make no mistake: the trajectory of Xyrem has everything to do with Jazz.

Jazz’s initial management team came from a company called ALZA Corporation, which had specialized in drug delivery systems and whose flagship tech included fentanyl and anti-smoking patches. In 2001, Johnson and Johnson acquired ALZA. Shortly thereafter, a group left to start a new pharma company with nothing more than themselves. For the first two years of Jazz’s existence, management focused on raising capital from private equity. Then, for $122.5 million, it acquired Orphan and Xyrem in 2005. It publicly offered shares two years later in 2007.

Surveying the field in 2009, you might not have expected Jazz stock to be a winner. First, Jazz was on the verge of bankruptcy. Second, as discussed above, Xyrem is an old compound and a relatively niche drug. Third, Orphan Drug exclusivity for Xyrem was set to expire.

Had this been your expectation, you would have been wildly wrong. Jazz may have been the single most profitable publicly traded investment opportunity from 2009 to 2015 in the entire universe.

Jazz’s improbable rise from the ashes of 2009 is almost impossible to understate. The significant majority of company revenue consisted of Xyrem sales, a drug at the very end of its original Orphan Drug exclusivity period. According to the Jazz CEO, the company in 2009 spoke “to bankruptcy attorneys every day.” But as its flagship drug was losing exclusivity, Jazz could not stop making money. It made so much off Xyrem from 2009 forward that Jazz’s stock price went from well below $1 to $150+. If you timed the lows and the highs, you could have made a 30,000% return on your investment in 5 years. Every $1 you put into Jazz could have become $300.

Put another way: if you had put your Bar Mitzvah fund into Jazz stock at 13, you would have been a multimillionaire by the time you entered college.

What saved the company? Price increases. Even though Xyrem’s original 7-year Orphan Drug exclusivity period expired in 2009, as discussed above, Jazz pushed up the price of Xyrem fourfold since 2006. Remember: Xyrem is basically the same as a compound that could be purchased OTC as a bodybuilding supplement in the 1980s for not-that-much-money.

According to this CBS article (links copied), Xyrem and these price increases saved the company from bankruptcy:

In 2009, Jazz was on the brink of bankruptcy. It became a penny stock. It put its drug development program on hold in order to service its debt; it laid off 24 percent of its workforce and cleaned house among management, replacing its CEO and CFO.

To rescue itself, Jazz began upping the price of Xyrem. The price hikes worked. Jazz's Q3 2010 "set a new record," CEO Bruce Cozadd told Wall Street in a conference call in which he also said 2010 was "a pivotal year." In a recent note to investors from Jefferies & Co. analyst Corey Davis, a chart of Xyrem's spiraling price was labeled "To the Moon, Alice!"

Even today, 20 years after introduction, Xyrem remains unconscionably expensive and absurdly profitable. The cost for 180 milliliters of Xyrem is almost $6,000, which is an order of magnitude higher than the street price.

This meteoric rise eventually helped fuel the acquisition of another company, GW Pharmaceuticals that made its fortunes largely by selling a single product, Epidiolex or branded, purified CBD. Not surprisingly, Epidiolex costs $32,500 per year, well above the market price for FDA-unapproved CBD. And btw, some research suggests that unapproved CBD-rich products with other cannabinoids are more effective for epilepsy might be superior to a purified CBD extract.8

Again, it is hard to understate Jazz’s improbable success over this period in raising prices year after year on a single off-patent compound that has been around and in circulation for decades. In 2013, Fortune named Jazz number 1 in its fastest growing companies. According to FiercePharma, between 2007 and 2014, no drug maker increased prices more than Jazz did with its narcolepsy drug, Xyrem.

So how did this really happen? Turns out, none of it is secret.

The Jazz Patient Assistance Programs

First, as FiercePharma also noted, a Jazz patient assistance program (PAPs) helped insulate patients from price hikes. Due to the Great American Drug Machine™, rarely do patients directly bear the brunt of price hikes:

Yes, we all pay for these price hikes. But rarely do you see it directly. The cost of price increases gets absorbed into different parts of the Great American Drug Machine™—some line item for a PBM and/or insurance company that gets mashed into an increase in your annual insurance premiums or in the case of Medicare, gets passed on to you, the taxpayer. I think. I really can’t be sure. You can’t always see under the hood of this monster.

PAPs are another part of the obfuscation. Often structured as non-profits—and funded by pharma companies themselves—PAPs offset out-of-pocket drug costs for patients and thus, provide pharma companies PR benefits. They allow companies to (1) significantly raise prices and (2) simultaneously say no patient that needs a drug will be left without. That’s what Turing did with Daraprim. But let’s be clear. This is not a Martin Shkreli problem. It is an industry wide practice. To quote a Georgetown professor and doctor who’s studied pharma marketing practices for three decades: this is an industry practice to “deflect criticism of high drug prices.”

To recap, PAPs do improve access to drugs for those who cannot afford them. But they also allow drug companies to increase the prices of drugs and get more money out of insurance companies and save face. They also may increase demand for branded products by offsetting cost differentials to patients. A 2017 report from Citi Research, every $1 million infusion from a pharma company into PAP “charity” can generate up to $21 million in sales. Other research has found it difficult to tease apart how PAPs affect drug prices because of a lack of transparency. According to a CRS report:

Drug manufacturers say the generous aid is evidence of their commitment to patients who cannot afford a prescribed course of medication. Many manufacturer programs are designed to reduce consumer cost sharing for high-cost specialty drugs used to treat cancer, hepatitis C, Crohn’s disease, and other serious conditions. Industry analysts and [HHS] say that the programs also are used to bolster prescription drug sales and prices and can increase costs for government and commercial health payers. For example, an insured consumer may use a manufacturer coupon to buy a more expensive brand name drug even if a lower-cost generic is available. Although the coupon reduces the consumer’s cost-sharing obligation for the drug, it does not cut the price paid by the consumer’s health care plan.

Thus, some theorize that PAPs “may lead to higher drug prices as a result of the interplay between patient demand and prices.” No shit. Remember my rule:

“The opaquer a financial instrument or transaction, the more likely you are getting f*cked.”

--Me

PAPs have existed for a while. But after Medicare started picking up the tab for prescription drugs in the early 2000s, they grew in popularity.

In the case of Jazz, the company set up a non-profit patient assistance program in 2011 to help offset rising Xyrem prices called the Narcolepsy Fund. And in 2019, the Department of Justice shut it down (along with many other pharma PAPs) under anti-kickback statutes. I’ll just quote the Jazz settlement papers:

In 2011, Jazz asked [Caring Voice Coalition] to create a fund that would pay the copays of certain Xyrem patients, including Medicare patients. CVC then agreed to establish a “Narcolepsy Fund,” and Jazz was the sole donor to the fund. Xyrem accounted for a small share of the overall narcolepsy drug market. Theoretically, the CVC Narcolepsy Fund could cover patients taking any narcolepsy medication, but, in practice, it almost exclusively assisted patients taking Xyrem. Jazz donated to CVC with this understanding. Moreover, CVC disadvantaged any patients seeking assistance for two competing narcolepsy drugs by requiring them to obtain a denial letter from another assistance plan before being eligible for CVC assistance. Jazz knew or should have known that CVC favored patients taking Xyrem, and disadvantaged patients taking other medications. In conjunction with the establishment of CVC’s Narcolepsy Fund, Jazz changed the eligibility criteria for its program that provided free Xyrem to patients who could not afford it and, as a result of this change, Medicare patients no longer qualified for the program. Instead, Jazz directed its distribution vendor to refer any Xyrem Medicare patients with unaffordable copays to CVC in order for Jazz to generate revenue from Medicare and to induce purchases of the drug, which resulted in claims to Medicare to cover the cost of the drug

Jazz Works the REMS

Next, some say Jazz used the REMS as a tool to block competition.9 For example, Jazz noted in a 2017 SEC statement that it had petitioned FDA to refuse to approve any generic sodium oxybate that omits instructions covered by Xyrem patents:

In September 2016, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc., our wholly owned subsidiary, submitted a Citizen Petition to the FDA requesting that, for safety reasons, the FDA refuse to approve any sodium oxybate ANDA with a proposed package insert or REMS that omits the portions of the Xyrem package insert and the Xyrem REMS that instruct prescribers on adjusting the dose of the product when it is co-administered with divalproex sodium (also known as valproate or valproic acid). In January 2017, the FDA granted the Citizen Petition with respect to the Xyrem package insert, concluding that it will not approve any sodium oxybate ANDA referencing Xyrem that does not include in its package insert the portions of the currently approved Xyrem package insert related to the DDI with divalproex sodium. Our Xyrem DDI patents cover these instructions on the Xyrem package insert and Xyrem REMS.

Earlier, in 2012, Jazz did the same thing. Indeed, Jazz engaged in “roughly seven years of discussions and disagreements between FDA and Jazz about the REMS,” arguing for more severe regulatory restrictions. FDA decided to waive the REMS requirement, however, for generics in 2017. An internal memo explains why:

In August 2009, Jazz proposed eliminating the single pharmacy and instead allow certification of multiple pharmacies contenting it would it “increase patient access without compromising patient safety.”

Months later, Jazz proposed a REMS with multiple certified pharmacies along with a new drug application seeking a new indication for fibromyalgia.

After FDA refused to approve the fibromyalgia application, Jazz flip-flopped and again adopted the position that a single, central pharmacy be used to administer Xyrem prescriptions. By that time, as FDA notes, Jazz had listed several patents related to the REMS listed in the Orange Book.

In August 2012, FDA indicated the final REMS should not contain the single

pharmacy limitation believing that a single pharmacy was neither necessary nor appropriate to ensure the safe use of Xyrem.

In SEC filings shortly thereafter, Jazz noted that the REMS were currently protected by method of use patents covering distribution of Xyrem and depending on if those REMS changed, the ability of Jazz to protect Xyrem against generic competitors could be reduced.

FDA tried to close discussions in December 2013, prompting Jazz to file a formal dispute resolution request, claiming FDA’s decision put “patients and others at risk.” Again, the pharmaceutical company advocates for more restrictions. FDA denied the request, prompting an appeal. FDA explained it had two public health goals: “(1) to have a REMS that assures safe use of the drug, and (2)

to ensure that the REMS does not stand in the way of generic approval.”

FDA “note[d] the inconsistent position” Jazz took on the REMS which suggested the company knew its REMS “could have the effect of preventing generic competition.” Nonetheless, FDA capitulated:

Of course, what explains Jazz’s “inconsistent position”:

Jazz Gets Patents

When Jazz acquired Orphan in 2005, Orphan had no patents. It had patent application No. 10/332,348. That application would not issue until years later. Further, as I noted in a prior essay, patent applications can breed.

Over time, the REMS patent application did breed numerous children and grandchildren.

Jazz built up two other patent families alongside the REMS family. One, the ‘431 family, claims priority to 2004 and encompasses pharmaceutical compositions of GHB—and methods of making and using such compositions—that are chemically stable and microbial resistant, without the need for a preservative. A second, the ’302 family, claims priority to 2013 and encompasses methods of administering GHB in conjunction with other medications used to treat seizures.

Jazz would list most of these patents in the Orange Book.

Jazz Sues Potential Competition

The rapidly escalating profitability of Xyrem did not go unnoticed by generics, and starting in 2010, generic manufacturers began to move into the billion-dollar GHB market. In July 2010, Roxane Labs submitted an Abbreviated New Drug Application to make a generic. Eight other generic manufacturers would follow.

Jazz sued. Not each company once or twice. Over and over. Between November 2010 and August 2016, for example, Jazz sued Roxane (acquired by Hikma) nine times on different patent properties from the three patent families.

By operation of law, the first suit triggered the automatic 30-month regulatory stay in the approval process for generic Xyrem—whether it had merit or not. Then, according to the generics, Jazz engaged in a strategy they described as “cyclical litigation”: “assert a patent position, glean defenses to that position in the litigation, file new ‘follow-on’ patents, and then file a new lawsuit asserting those patents.” To further prolonging the lawsuit, Roxane/Hikma in a December 2013 filing a pattern of tactical maneuvering “to keep the Xyrem cash cow alive”:

It seems that every time the parties get a toehold on completing discovery, Jazz employs some sort of delay strategy. First, Jazz continually expanded the scope of this lawsuit, from five patents in 2010 to the current ten patents. When each new patent issued, Jazz filed a new suit that was consolidated into this action, which in turn would cause delay of this case to accommodate fact discovery on the newly added patents. Now on the eve of expert discovery, Jazz has embarked on a bifurcation strategy to try to cause still further delay. Like Sisyphus rolling the boulder up the hill, it is one step forward, two steps back, seemingly without end. Although Jazz filed this suit more than three years ago, we are not even finished with discovery.

As a different court in the In re: Xyrem (Sodium Oxybate) Antitrust Litigation noted in 2021:

Jazz’s lawsuits thus imposed a stay on ANDA approvals through at least mid-2020 (i.e., 30 months from November 2017). Indeed, as of today, more than a decade later, there is no generic version of Xyrem.

That remains true today. GHB has been around forever. It isn’t patented. But there are no generic GHB product on the market.

The PTAB Takes Down (Most of) the REMS Patents

After Jazz grabbed its regulatory stay, the generics struck back. They petitioned the Patent Trial and Appeals Board (PTAB) to review the validity of the Jazz’s REMS patent suite using the same procedure Freedom to Operate tried to use to cancel the Polymorph A patents (which will up in the Orange Book).

The generics mostly succeeded with the challenge. The PTAB instituted review on almost all petitioned claims. Certain claims of the ’963 patent (the REMS patent described in the intro) evaded review. (We’ll come back to that—it is important.) After instituting review, the PTAB cancelled all challenged claims based on pretty good art: the materials Orphan had submitted to FDA in 2001 when Orphan had been been trying to get approval of Xyrem.

For each instituted patent, the PTAB agreed the 2001 materials disclosed most elements of the petitioned claims. For missing elements, the differences between the art and the claims were slight and thus, obvious. For example, the materials did not show a “central computer database being distributed over multiple computers.” But—as if this needs to be said—using multiple computers “to provide the capacity and efficiency needed to control nationwide distribution of the prescription drug disclosed in the ACA, would have been a predictable use of a known distributed processing system according to its established function.”

That left just one other issue: whether the 2001 materials were, in fact, prior art. The PTAB concluded that they were.

Not all printed material is prior art. Only material that is publicly accessible or available one year before the priority date can be prior art. The touchstone of this inquiry is whether material has been disseminated or otherwise made available such that a person interested and ordinarily skilled in the art exercising reasonable diligence could locate it.

In the case of the 2001 materials, the PTAB found that prior to the filing of the patents, notice of the meeting had been published in the Federal Register, which included a hyperlink where the materials submitted to the FDA could be found. These materials were then made available at the linked site prior to the priority date for each patent. Evidence, such as the Web Archive, supported public availability by October 2001—more than one year before the December 2002 priority date.10

Jazz Settles the Lawsuits

Jazz appealed the PTAB’s decision cancelling most (but not all) of the REMS patent claims. In the meantime, while the case was on appeal, Jazz settled out the cases against the generics one-by-one.11 In all, these settlements effectively ended the patent litigation campaigns and preserved Jazz’s GHB monopoly for more years. According to the settlements:

Xyrem would maintain its monopoly until December 31, 2022.

On January 1, 2023, Jazz would introduce an authorized generic and split profits with Roxane/Hikma;

On July 1, 2023, Jazz would introduce several more authorized generics, and split profits with other generic manufacturers. Roxane/Hikma could launch its own generic on July 1, 2023.

On December 31, 2025, the other generics manufacturers could launch their own generics.

And the Xyrem gravy train kept rolling. Revenue and sales continued to grow. $1.4 billion in 2018. $1.6 billion in 2019.

And When They Say The Party's Over, Jazz Brings It Right Back

In 2020, with generic GHB soon to enter the market, Jazz introduced a low-sodium version of Xyrem called Xywav. And it got more Orphan Drug designations to boot.12

FDA considers Xywav to be clinically superior to Xyrem. Xywav “provides a greatly reduced chronic sodium burden compared to Xyrem.” As this web article explains:

Since Xywav’s first FDA approval last July for both cataplexy and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) associated with narcolepsy, its uptake in the US has soared, driven mainly by the favourable safety profile of its reformulation. This reformulation contains 92% less sodium in each dose compared to its predecessor and the gold standard of narcolepsy treatment, Xyrem (sodium oxybate). Because of this, Jazz is expected to undertake a switching strategy from its top-selling and market leader brand, Xyrem, to Xywav in order to offset Xyrem’s sales decline due to generics erosion as the brand approaches a loss of patent exclusivity in 2023. Given Xywav’s strong clinical and commercial profile, GlobalData expects its exponential growth trajectory to continue into 2027, reaching around $1.3bn in global sales.

A quick Orange Book check on Xywave shows an armada of issued patents with expiration dates into 2033.

As this publication explains, this seems to be an attempted (and perhaps rather transparent) attempt to “product hop”: when “a pharmaceutical manufacturer winds down production of an old drug formulation whose patent expiration date has passed or is approaching” and “then forces or persuades patients to switch prescriptions to the drug’s new – and newly patented – formulation.”13

But, as we’ll next see, there is a threat on the horizon that could ruin the party…

This two-part standalone essay relates to the Psychedelic Patent Wars essays.

And perhaps more so from partnered sex than solo activities.

To be fair, the researchers identified other clinical differences, including that GHB “had a shorter timecourse” and “was more likely to cause sleep.”

The original Orphan Drug Act of 1983 also defined rare diseases more flexibly as “any condition which occurs so infrequently in the United States that there is no reasonable expectation that the cost of developing and making available in the United States a drug for such disease or condition will be recovered from sales in the United States of such drug.” Rare diseases today means a disease or condition that affects less than 200,000 people.

Do these underlying concepts or principles resonate? What about a Controlled Substances Development Program that gives tax credits and 7-year Orphan Drug style exclusivity to the first company to develop a known scheduled but unpatented compounds for a disease or condition. Maybe this solves our “psychedelic patent” problem—or at least addresses many of the underlying causes?

Recently, the Eleventh Circuit in Catalyst v. Becerra poured water over FDA’s interpretation of the phrase “same disease or condition” as same “use or indication” that may impact one variant of salami slicing. The Orphan Drug Act bars FDA from approving another new drug application “for the same drug for the same disease or condition” for seven years after approval of the orphan-designated drug. For three decades, FDA interpreted that language to provide exclusivity as to an approved indication, which as discussed above, could be subpopulation narrower than the the disease or condition. At issue in Catalyst was two companies selling the same drug to treat the same disease but in two different subpopulations: adults and pediatrics. The Eleventh Circuit ordered FDA to rescind the approval for the later drug, which blocked by approval of the earlier drug. According to the Eleventh Circuit’s decision, orphan drug exclusivity includes the entire disease or condition—not just a single indication.

The above quoted passage makes you wonder why, in response to a rescheduling petition I submitted in February 2022 on behalf of a medical clinic, DEA refused to consider referring the petition to HHS as the CSA requires. Indeed, many say that FDA approval is a prerequisite to any rescheduling. As a historical matter, this is false—or at least it is not true when pharma develops a drug.

Let me now pose a deep question: do you think FDA’s strict safety/efficacy and clinical trial requirements promote public health, all things considered? Reflexively, many assume that the FDA clinical trial process keeps us safe. But if compliance with that process ultimately multiplies the price of medicine and therapies 10 or 20-fold—for example, paying $30k for CBD—isn’t there a good argument that if we look at the health system as a whole and include economic considerations, society might actually be better off, healthier, and happier with something different, perhaps less strict or demanding regulation? Just a thought.

Much of the facts described herein are currently being litigated in In re: Xyrem (Sodium Oxybate) Antitrust Litigation, which concerns allegations that Jazz has engaged in anticompetitive conduct to maintain exorbitant prices for Xyrem. I will discuss the case in a subscriber only post that follows Parts 1 and 2. But you can read about the case in the linked court opinion.

So, again, if you are going to submit information to the FDA or clinicaltrials.gov or whatnot related to a future patent filing, make sure to talk to a patent attorney first.

One company stayed the course of the appeal: Amneal Pharmaceuticals. On appeal the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision.

FDA gave Xywav 7 years of Orphan Drug Exclusivity for (a) cataplexy or excessive daytime sleepiness in patients 7+ years of age and with narcolepsy and (b) idiopathic hypersomnia in adults. Unclear whether the salami sliced first designation is proper under Catalyst.

A “corporate inversion” in 2011 also contributed to Jazz’s meteoric rise. Jazz, then-based in California, acquired Azur Pharma, a small Irish pharma company in Ireland. Because the deal transferred more than 20 percent ownership of the post-merger company to foreign holders, Jazz could do an “inversion” and relocate its corporate headquarters to Ireland. In so doing, Jazz could dodge U.S. taxes regime.

Xywav right now $18,000/month. You would have to make 320,000 pre tax for one year. I am duo degreed and can’t afford this. This is a drug that had been around for years. It doesn’t use new technology (gene splicing etc) Why so expensive? Greed.

This is a great collection of links/documents.