Introduction

I spent my earliest years as a practicing lawyer doing what most fresh, wet-behind-the-ears Columbia Law School grads with six-figures-of-law-school debt do: working at big New York firm. And if you did litigation and happened to graduate in 2012, that meant a large chance of ending up on at least one 2008 financial crisis docket.

For many businesses, the years following 2008 financial crisis amounted to famine. But for firms representing banks, it was a feast. Lawsuits and investigations everywhere. Even on vacation, I spent entire weekends poring through e-mails and documents. Tens of thousands of them. It was tedious work, but believe it or not, great training. I learned many sobering lessons about litigation, people, and life. And here is one of them: the opaquer a financial instrument or transaction, the more likely you are getting f*cked.

Many parties could be blamed for causing the 2008 financial crisis. No need to do a full explanation here—there are some pretty good books and movies about it, including the one below. At the end of the day, it was the system itself: An intricate web of convoluted financial transactions formed around opaque financial instruments with acronym names, like the CDS (Credit Default Swaps), CDOs (Collateral Debt Obligations), and Synthetic CDOs.

These instruments were thought to reduce risk. In reality, they just obfuscated it while Wall Street snagged transaction fees. As documented in the movie the Big Short, the CDS allowed one to bet against mortgage bonds by taking out insurance against a default, while allowing the seller of the swap to increase yield by collecting a periodic insurance payment. Meanwhile, the CDOs allowed banks owners to package up mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and resell them en masse as a “better” risk adjusted product. The synthetic CDO allowed Wall Street to repackage CDOs into other structured products.

This was, supposedly, “innovation.” In reality, it was impossible to see what was going on. In the abstract, maybe these ideas are not entirely bad. But over time, greed and self-interest took it all too far. The system began to hide risk and transaction fees. Many didn’t know what they were buying or selling—or at least, not the full profile of the structured products. Products were held out to be something they were not. And while Wall Street made a lot of money shuffling paper back and forth, in the end you—the consumers and taxpayers—footed the bill for baling it out.1

A particularly relevant cog in this scheme was the “CDO manager.” The CDO manager acted as a middleman for shuffling around CDOs and other structured products. He curated the paper that made it into a CDO, that would then be sold to others.

Admittedly, to this day it still isn’t entirely clear to me what a CDO manager does. There are a lot of jargon terms involved, such as “warehousing,” the intermediate step of a CDO transaction that involves purchasing loans or bonds that will serve as collateral. My understanding is about the same as this scene from the Big Short. The CDO manager’s name in real life is Wing Chau. You can find the SEC opinion regarding his real life activities here.

Importantly, it wasn’t clear who the CDO manager actually worked for: those buying the CDOs or those supplying the CDOs. (Start at :34 of the video.) A CDO manager received fees from asset or securities originators (the banks), which the CDO manager used for his asset pool. But those CDOs were sold to customers. (If you are interested more in the CDO, Yale Insights just released a special project on CDOs. I haven’t read.)

To describe these arrangements as opaque is an understatement.

On a philosophical or abstract level, to me, there are three synergistic issues with opaqueness and complication when it comes to the consumer.

The first is obvious: you can’t see where any of the money comes or goes.

Next, compounding. The more transactions involved in delivering a product or instrument, the more players or agents are involved. The more players involved, the more skimming. If in one transaction, the seller needs to make her margins, she marks up the price for the buyer. More players, more mouths to feed. If the actual cost of a product is $10 and 9 players need a 10% slice, the product ends up more than doubled.

Finally, and importantly, in any transaction involving agents or intermediaries (like the CDO manager), there are “agency” problems. In brief, the agency problem describes the conflict of interest where one party is expected to act in the best interest of another but when incentives or motivations present themselves to an agent to not act in the full best interest of a principal—as in for themselves. And when a transaction or product is opaque, enforcing the agency relationship through legal and contractual duties becomes difficult.

The Great American Drug Machine™

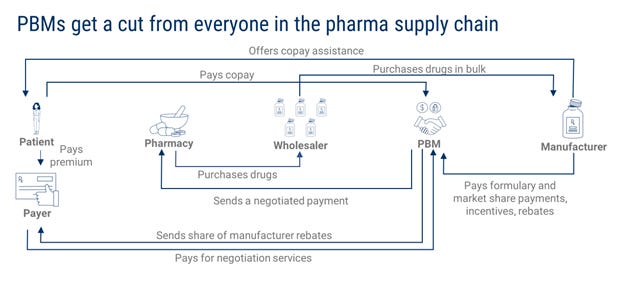

But this essay, of course, isn’t really about the financial system leading up to the 2008 crisis. That was all an allegory, my friends, for another currently operating system that rivals it in opaqueness and complexity: the American model for distributing pharmaceutical drugs. Here is a picture of it that I pulled from the internet.

Let’s break it all down.

Drug manufacturer researches, develop, and produce drugs. These are the companies like Pfizer or Merck.

Payers are typically insurance companies and health care programs—those that pay for care other than patients themselves—like Blue Cross or Medicare.

PBMs or pharmacy benefit managers are like agents of payers who negotiate prices on behalf of the payers. Express Scripts, CVS Caremark, and OptumRx are the three largest PBMs and control around 80% of the market.

Wholesalers buy large quantities of drugs and distribute them to pharmacies. Three wholesalers constitute 85% of the drug distribution market: McKesson, Cardinal Health, and AmerisourceBergen.

Pharmacies are…pharmacies. They can be a storefront, online, or part of a hospital.

And then there is the patient: you.

This system is opaque and complicated, and therefore, I believe, not designed to benefit you. It is designed to benefit everyone other than you. With so many players involved taking an ounce of flesh, the consumer ends up paying a price far in excess of the cost of production.

The drug companies probably make the most money in the deal, but arguably, they add the most value. The drug manufacturers do the R&D. They make the drugs. The wholesaler, payers, and pharmacies add value too, albeit probably not as much. Wholesalers transport drugs. Payers perform an actuarial service of managing risk. Pharmacies manage the point of sale.

That leaves the PBMs. What do they do? I’m going to throw down two images made by other folks.

PBMs

PBMs manage drug “formularies” or lists of covered medications on behalf of health insurers. Specifically, PBMs:

Maintain drug formularies

Use their purchasing power to negotiate rebates and discounts from drug manufacturers

Contract with pharmacies and other points of sale for dispensing drugs to reimburse for drugs dispensed to beneficiaries.

It was not always this way. PBMs were formed in the late 1960s to help insurance companies process unwieldy prescription drug claims and reimbursements. But by forming and controlling large patient networks and claims, PBMs became able to command something greater: negotiating power from other players in the the Great American Drug Machine™2. The players had no choice but to contract with PBMs. Amazingly, PBMs went from helping with the paperwork to controlling the drugs you get prescribed through the “drug formulary,” i.e., a list of prescription drugs available on a health plan.

The video below does a far better job of explaining it than I can.

Here is the key point. PBMs used to generate revenue by charging administrative or service fees from contracts private health plans for doing paperwork. Over the years, they “innovated” and have come to use their purchasing power to work both sides of the deal: rebates from manufacturers. Supposedly, this is for your benefit, as the purchasing power allows PBMs to negotiate down prices. Manufacturers give PBMs rebates to promote use of their drugs and achieve preferred status in a formulary. But this rebate model inflate and obfuscate drug prices as health plans generally evaluate PBMs on rebates rather than net drug spending. And because none of this is transparent, margins are hidden.

You see where I’m going with this. I cannot help but see parallels between the CDO manager and CDO on the one hand and the PBM and the drug formulary on the other. The parallel isn’t exact by any means, but at bottom, both are glorified middlemen selling structured products.

Recall, in finance, the CDO was a conglomeration of mortgage bonds grouped together, which obscured the underlying value of the underlying instruments. CDO Managers would create CDOs by taking in mortgage bonds (and fees) from banks and and selling the CDOs to institutional investors, creating a whole host of conflicts of interest along the way.

The drug formulary and PBMs are somewhat similar. Formularies are a list of preferred drugs, which influence which drug products get prescribed and used by patients and prescribers. Supposedly, by structuring groups of drugs together in a formulary, PBMs offer payers the greater value—as in the formulary offers the best bang-for-buck of clinically effective options—in the same way the CDO provided better value and returns by structuring mortgage products together and reducing risk. And supposedly PBM’s apply their expertise and management skills to reduce prescription drug costs. They frequently update formularies by adding new approved drugs and adding/removing existing drugs based on PBM-manufacturer contracts.

But of course, like CDO managers, PBMs get rich off of fees from all sides of the transaction and the aforementioned “rebate” concept. Not surprisingly, this opaque manner of getting prescription drugs from the manufacturer to you—by way of the PBM—has given rise to some dubious practices, such as spread pricing. That is when PBMs charge payers/health plans more for drugs than they reimburse to pharmacies and pocket the difference. There are also competition concerns. And many others.

What is Being Done About This?

It isn’t a great time to be a PBM.

Last month Senators Grassley and Cantwell introduced the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act of 2022, which among other things, bans spread pricing. Wouldn’t hold your breath waiting on that. It is Congress after all.

Last month, the FTC launched an inquiry into PBM practices by a 5-0 vote. “This study will shine a light on these companies’ practices and their impact on pharmacies, payers, doctors, and patients.” Also, Republican House members recently asked the Government Accountability Office to study PBMs’ role in the pharmaceutical supply chain.

And in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, a monster False Claims Act (whistleblower) lawsuit from a 19-year employee and former executive at CVS Caremark, the head honcho of PBMs, got unsealed. The complaint lays out an alleged scheme to defraud Medicare Part D beneficiaries from accessing less costly, equivalent versions of numerous generic prescription drugs in favor of much costlier, rebate laden brand-name drugs.

And finally, I’d be remiss not to discuss the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company.

Cuban’s latest venture, a Public Benefic Corporation, buys off-patent generics directly from manufacturers and resells them to patients online after adding a 15% markup to its acquisition cost, plus a $3 fee for pharmacy labor and a $5 shipping fee. In a few words: No PBM, transparent pricing. All drugs in the pharmacy are priced according to a simple equation: “manufacturer’s price” + 15% markup + $3 pharmacy dispensing fee per drug, per order. No PBM, no rebates, and no sausage making in a back room. It is being made at the front of the store, right before you. And maybe it doesn’t taste any better, but you know exactly what you are going to get.

There are many reasons to praise the MCCPDC. For starters, it has a cool, descriptive, IDGAF no-nonsense name—a name that stands directly opposed to an industry that spends oodles on marketing to, among other things, come up with names for drug products that sound like Sonata®, Lunesta® and AcipHex®. Want to know what MCCPDC does? See title. It markets itself.

According to the WSJ, the MCCPDC could save Medicare $3.6 billion per year if it used MCCPDC to directly purchase generics rather than the Great American Drug Machine™.

The MCCPDC has been called a “disruptive innovation.” But it isn’t immune from criticism. Martin Shkreli, of all people, levies several critiques of the MCCPDC. He argues, for example, that MCCPDC does not create any real cost-savings for patients. Also, the MCCPDC is not a new concept. Online pharmacies or websites such as GeniusRx and GoodRx offer a similar service and show prices for many generic drugs at or below the MCCPDC. Shkreli contends, the “cost savings” isn’t as dramatic as the MCCPDC holds out and MCCPDC should compare its prices to these competitors on an apples-to-apples.

Maybe he’s right. To see if the criticism holds water, I looked at other drugs like Abilify. The “Retail Price” isn’t what you’d pay on the open market for similar generic products. So it isn’t an accurate reflection of cost savings if you are comparing MCCPDC to the next cheapest options. But I did find some other examples of MCCPDC offering the cheapest prices. So, I’m not prepared to join either bandwagon.

But in my view, these criticisms somewhat miss the point. The point of the MCCPDC PBC isn’t just to save you money, it is to be transparent with pricing. Hence, on its website:

Our prices are the true cost to get each medication from the manufacturer to you. We cut out the pharmacy middlemen and negotiate directly with manufacturers to get the best possible price. Then, we show you exactly how much you’ll pay for us to keep our business running and how much it will cost to prepare and ship your prescription.

The fundamental value or principle of MCCPDC doesn’t appear to be offering cheaper drugs or even to be profitable. Rather, it is about transparency. Cut out the PBM and show you exactly what they pay for the drug and what the markup is. That is what you pay.

Maybe I’m wrong. Honestly, the drug pricing business is not my strong suit. Perhaps, I’m getting duped. But Mark Cuban is a guy with a $4 billion net worth. I just find it hard to believe that he is jumping into the hypercompetitive generic pharma industry and putting his mug on the face of a website to make 15% margins. Rather, it looks like he wants to troll the Great American Drug Machine™. MCCPDC is an attempt at giving a giant middle finger to the system: showing how we can get drugs to people without all the nonsense in the middle and not lose money.

And for this reason, I don’t find the listing of high retail prices in comparison to MCCPDC to be deceptive at all, even if nobody pays sticker. Isn’t the whole point of the company to show you the sham and absurdity of it all?

Conclusion

Innovation in the drug market can happen in many ways. In its most apparent and conventional form, drug companies find new molecules or new applications of old molecules. But in my view, the most disruptive technologies won’t be new drugs that slot into existing systems. Rather, the Most Innovative Drug Company in the World™ is a company that doesn’t do anything innovative at all. It may not exist yet. The Most Innovative Drug Company in the World™ is a company that manages to fix the supply chain and changes the system itself.

That includes, by the way, psychedelic medicine. Some see psychedelics as medicine not just as an innovation but a disruptive technology—a referendum on existing mental health paradigms—that will require entirely new infrastructure to support. Some see psychedelics as “exceptional.” In many undeniable ways, this view is correct. Psychedelic therapy will need, among other things, psychedelic therapy clinics and a generation of therapists trained in the art.

But as more time goes by, I become less and less convinced that psychedelic medicine3 will be as shocking to the system or as exceptional as folks hold it out to be. Seriously, just look around. Look at the boards of these companies and non-profits. Most or all of them are populated by folks who used to work in pharma. This is neither a positive nor negative observation, just an observation. People who grow within a system, learn within that system, and profit from that system are rarely the ones who change it. Similarly, folks coming from cannabis and trying to ape that playbook—playing apex predator in hopes for a lucrative buyout, perhaps a big pharma acquisition—aren’t going to be the ones to change much either.

Again, I levy no judgment at these emerging arrangements. It is entirely logical. Whatever one thinks about FDA approved psychedelic medicine, it is hard to argue against the notion that the most linear path to bringing psychedelics to market at this point in history is through the FDA. And due to regulatory barriers, that requires exceptional organization, expertise, and capital.

My only point in this conclusion is to say we should not miss the forest through the trees. Psychedelic medicine, if or when it happens, may be a paradigm shift. But if (or when) psychedelic therapy gets slotted into existing systems, such as the Great American Drug Machine™, much will necessarily remain the same. And if psychedelic pharma requires all sorts of new infrastructure within the same type of convoluted drug delivery and payment systems we have now, it is quite possible this system could be more opaque and have more middlemen—none of which actually benefits you.

I’ll save politics for another day, but the rise of populism in the United States and the rest of the world, in my view, can be directly traced to this failure.

There is, of course, no type of intellectual property rights associated with the “Great American Drug Machine.” It is not even original, but a play on Taibbi’s article about the Great American Bubble Machine.

My comments here are strictly limited to psychedelic medicine, not other aspects of the so-called psychedelic revolution.