All that Jazz

An ode to REMS and tying

My day-to-day is not spent dealing with drug policy issues. I’m a litigator with a focus on IP and competition issues. And yet, it has been a while since I’ve written about these topics. So, today, I do. And, since this is a newsletter “On Drugs,” I should mix-in drugs, right?

The FTC’s Orange Book Crackdown

Last fall, the FTC, supported by FDA, issued a policy statement condemning improper Orange Book listings:

Improperly listing patents in the Orange Book may harm competition from less expensive generic alternatives and keep prices artificially high, according to the policy statement. The FTC will scrutinize improper Orange Book patent listings as potential unfair methods of competition in violation of Section 5 of the FTC Act.

Recall, around a year ago, I explained Orange Book listings—the lifeblood of any for-profit pharmaceutical company’s balance sheet.1 Patents in the Orange Book that cover a compound or use of a compound have particular value because the holder of an Orange Book patent can procure an automatic 30-month stay of regulatory approval of a competitor’s product by filing a patent infringement suit against the competitor asserting the patent.

GHB, Orphans, and REMS: A Regulatory Love Story (Part 1)

Interested in psychedelics, psychedelic regulation, and/or psychedelic patenting? Or, do you have a pharma fetish (like me)? Either way, pay attention to this one. I’m going deep. Around a month ago, in the District of Delaware, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) filed an

Did the Jazz/Avadel dispute discussed above have anything to do with this FTC move? (Read Parts One, Two, and Three.) You bet. Separately, FTC Commissioner Lina Kahn issued her own statement:

Drug prices are sky high. Americans pay more for medicines that any other country in the world. A striking number of people now report having to ration their medicines or skip them altogether because they are too expensive. Many factors contribute to this unaffordability crisis—including unlawful business practices. We at the FTC are committed to using all of our tools to combat corporate conduct that unlawfully inflates drug prices.

That is why the Commission today is considering a policy statement on how the FTC will scrutinize improper “Orange Book” patent listings…. A brand pharmaceutical company can obtain a presumptive 30-month stay of the FDA approving competitors merely by listing a patent in the Orange Book and filing a lawsuit against a generic manufacturer, regardless of whether the patent it listed is actually valid or infringed by the competing generic product. In this way, a pharmaceutical company can weaponize the Orange Book to protect monopoly rights to a medical product—even if those monopoly rights are invalid. This practice can delay or block generic and innovative drugs from entering the market, keeping prices higher for American patients.

Kahn then explains how Orange Book abuse like this keeps lower cost generics—and sometimes a superior formulation—off the market:

The FDA tentatively approved Avadel’s extended-release version in 2022, but by that time, Jazz, another pharma company, had sued Avadel for infringing Jazz’s “Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies” (“REMS”) patent—a patent that had nothing to do with the drug itself or an approved method of using the drug. Jazz cited the Orange Book to automatically trigger the 30-month stay, blocking Avadel from the market. The Federal Circuit court eventually held that the patent was improperly listed in the Orange Book and ordered it to be delisted. Following this order, the FDA granted final approval of Avadel’s new drug—nearly ten months after the original tentative approval. In that intervening period, Jazz continued to rake in monopoly profits and patients were deprived of a potentially superior formulation of a critical narcolepsy drug.

Competition, naturally, drives prices down; so, keeping generic drugs off the market keeps drug prices high, as noted by FDA:

In November 2023, the FTC went on the prowl, challenging more than 100 patents as improperly listed in FDA’s Orange Book:

“Wrongfully listed patents can significantly drive up the prices Americans must pay for medicines and drug products while undermining fair and honest competition,” said FTC Chair Lina M. Khan. “The FTC’s action today identifies over 100 patents that we believe are improperly listed, affecting products ranging from inhalers to EpiPens. We will continue to use all our tools to protect Americans from illegal business tactics that are hiking the cost of drugs and drug products.”

This recent activity appears to be part of a broader FTC campaign of enforcing competition law in healthcare. While the FDA approves drugs before entry into the market, once a drug enters, the FTC becomes the regulatory agency responsible for policing anticompetitive conduct.

To understand how and why FTC sometimes gets involved, let’s briefly recap the contemporary posterchild: the Jazz/Avadel dispute.

Recap of Jazz/Avadel

As previously discussed, Jazz and Avadel are two publicly traded pharma companies with a long-running dispute centering on GHB, a compound in Schedule I of the CSA.

GHB has a history not unlike MDMA and other controlled substances. Like MDMA, GHB was first synthesized in the early 20th century, but was forgotten and unappreciated. The drug saw experimental medical use in the 60s, similar to MDMA in the 70s. By the 1970s, some evidence suggested GHB was effective in difficult to treat narcolepsy cases. But like MDMA, GHB had not made it through the FDA clinical trial process in the early years. Like MDMA as an unscheduled compound in the 1980s, GHB in the 1990s increasingly saw recreational use. It too became a club drug. And like MDMA, GHB was placed in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) and effectively banned it in the U.S.2

But GHB took a different route to Schedule I, however. Unlike MDMA—which entered Schedule I by way of DEA’s administrative process—Congress put GHB in Schedule I with legislation following the Hillory Farias and Samantha Reid Date Rape cases. That legislation bifurcated GHB’s scheduling: Schedule I for GHB, except FDA-approved pharmaceutical GHB in Schedule III. Indeed, it became the prototype for bifurcated rescheduling. Why?

By the late 1990s, a company named Orphan Medical had ushered GHB through the most of the clinical trial process. When Congress sought to place GHB in Schedule I, Orphan Medical was in the final throes of getting FDA approval for its GHB drug for the rare narcolepsy indication that had thought to have been effective decades earlier. Notably, in 2003, Orphan Medical would state the following.

Sodium oxybate (GHB) is a known compound and is not patentable. The Company has received orphan drug status for its indicated use of Xyrem in the U.S.. There are no license fees or royalty payments associated with Xyrem revenues. FDA orphan drug status extends through July 17, 2009. The Company has an issued formulation patent, which expires on December 22, 2019. Other patents are pending. The Company has contracted with third party bulk drug and drug product manufacturers for the production of Xyrem under GMP conditions.

Despite GHB being a “known compound” and “not patentable,” Xyrem—a drug which cost pennies to make and sold for dollars on the street—today costs patients and the health-care system $100,000+ for a years worth of treatment. How did an off-patent drug become so expensive?

Jazz’s initial management team came from a company called ALZA Corporation. After Johnson and Johnson acquired ALZA in 2001, the pharma team moved to the fledgling GHB-drug company. Management raised capital from private equity. Then, Jazz took over. First order of business? IPO. Next order of business? Raise prices.

In 2007, an annual cost of Xyrem was $11,169. Seven years later, the cost had jumped to $106,215. Today, Xyrem costs almost $200,000 for a years worth of treatment. I explain all this in Parts 2 and 3. The climax of the story is the fight between Jazz and Avadel.

The problem with Xyrem is that it is a drug that requires twice-nightly administration. To take Xyrem, patients must to wake up in the middle of the night to take a second dose. Avadel tries to come to market with a better mousetrap—a once-daily GHB administration.

Because of GHB’s history as a date rape drug, FDA required a REMS with Xyrem. The GHB REMS consisted of a computerized system for tracking which physicians can prescribe a drug and having a single, centralized pharmacy ship the drug to patients. Jazz obtained patents related to its REMS system, and it listed them in the Orange Book.

Jazz then mobilized its patents against Avadel. Nothing unusual there. But the patents Jazz asserted did not relate to the GHB or the method of using GHB. Instead, it asserted the REMS patents. Because the REMS was listed in the Orange Book, Jazz obtained the benefit of an automatic 30-month regulatory stay, i.e., automatically blocking approval of Avadel’s competitive drug for 30 months.

The FTC stepped in claiming that Jazz had inappropriately used the Orange Book patent assertion to block Avadel. A Delaware federal court agreed, and so did the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals. FDA’s approval of Avadel’s product had been contingent on the patent. And, with the patent removed from the Orange Book, FDA approved Avadel’s product. But significant damage had already been done for, even in losing, Jazz’s lawsuit kept Avadel off-the-market for many months.

Game over? Hardly. This dispute rages on. Other litigation between Jazz and Avadel on other claims continues. And, after losing its first bastion of defense, weeks after approval, Jazz sued FDA to open up a new front, challenging FDA’s clinical superiority decision concerning Avadel’s product. Many amici (friends of the court) have appeared in the case—all supporting Avadel.

Oral argument was set to be held this week on dispositive motions. Stay tuned.

Pioneer Psychedelic Pharma Co. Meets Competition Law

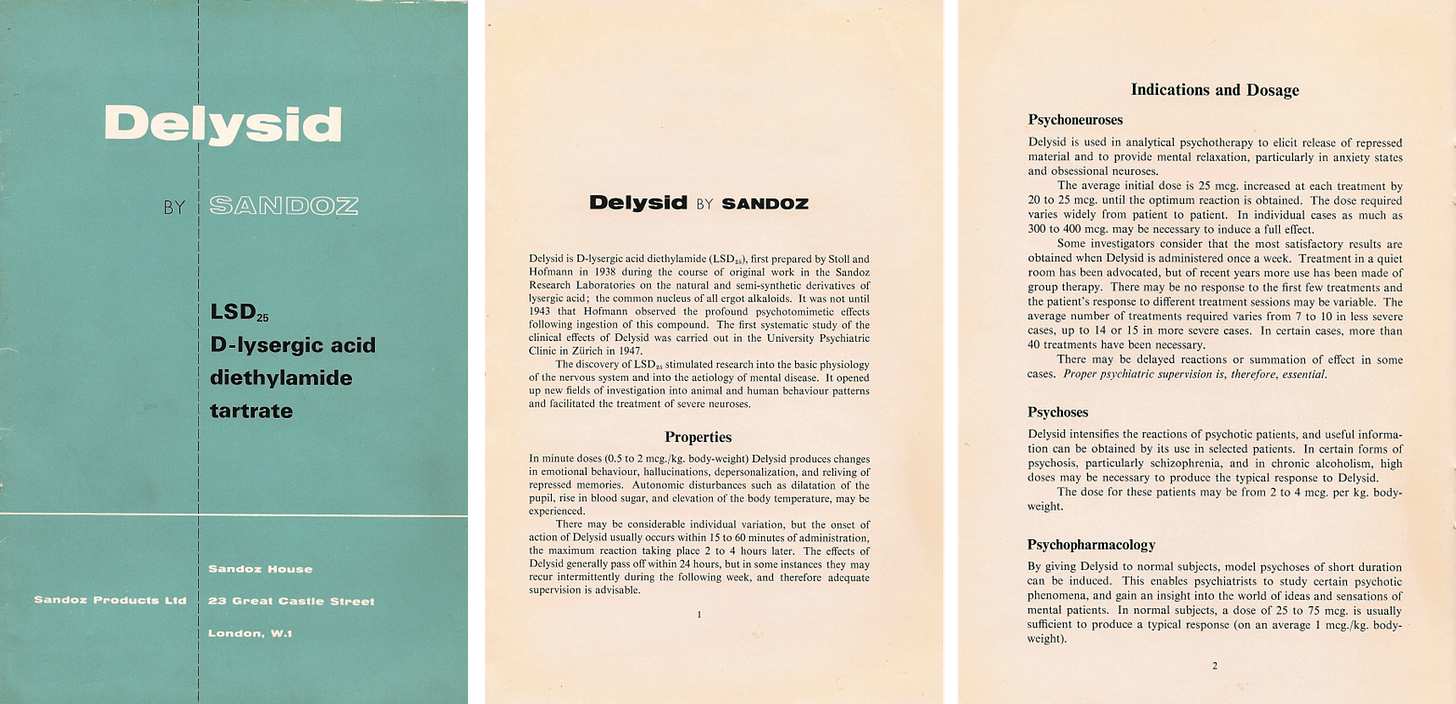

Not surprisingly, REMS—and REMS abuse—didn’t start with Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Xyrem. The concept is older and dates back to the OG psychedelic pharmaceutical company—Sandoz—home to Albert Hoffman.

Long before state service centers sprinkled the Oregon countryside and psychedelic-assisted therapy3 — Sandoz distributed LSD and psilocybin under the brand names Delysid and Indocybin as early as 1947. Sandoz distributed the drugs for psychotherapeutic uses and included with it a manual instructing on use.

How was this possible? Before 1962, the thalidomide tragedy, and the Controlled Substances Act, scientists and physicians could engage in pre-approval experimentation with little FDA oversight. There was no IND system. Drug companies could distribute samples nationally under the 1938 FDCA before approval if “intended solely for investigational use by experts qualified by scientific training and experience to investigate the safety of drugs.”

After 11 birth defect cases in the United States due to this sort “investigational” use, however, Congress gave preapproval control authority to FDA in the 1962 Amendments to the FDCA—giving rise to the system we have today. Sandoz distributed Delysid and Indocybin under these programs. And, after that, the CSA in 1970 put these drugs into Schedule I and layered on additional requirements for research.

The second development dampened the market for Delysid and Indocybin—which had never achieved FDA approval. So, Sandoz turned to other drugs, such as clozapine.

Clozapine

Clozapine has a familiar history. An older drug synthesized in 1958, early trials showed substantial positive proof of efficacy. Soon after clozapine became available in Finland. Then, 18 patients developed severe blood disorders. Nine died. Development in the US derailed.

By the 1980s, clozapine was off-patent—just like GHB, MDMA, ketamine, and DXM, etc. Yet, despite its off-patent status, today, clozapine is an approved and important medicine. How did the development happen? The Hatch-Waxman Act.

As I discuss here, the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act is the cornerstone of the modern system of pharmaceutical drug exclusivity and IP. Not only did the Hatch-Waxman Act introduce the Orange Book and sue-to-delay discussed above, but with that, introduced regulatory exclusivity, which provides a the holder of a New Drug Application limited protection from competition in the marketplace. And with the advent of exclusivity rights, Sandoz resumed development of clozapine, intending to leverage the exclusivity period to recoup development costs.

When approved in 1989, it became the first new drug for the treatment of schizophrenia in 20 years. Indeed, it was the only drug approved from treatment resistant schizophrenia. The FDA approved no new antipsychotic drugs between 1976 and 1989. May as well quote Wikipedia to explain why development continued after clozapine went off-patent and side-effects emerged:

Interest in clozapine continued in an investigational capacity in the United States because, even in the 1980s, the duration of hospitalisation, especially in State Hospitals for those with treatment resistant schizophrenia might often be measured in years rather than days.

In other words, there was a market need to treat intractable schizophrenia.

To address the blood issue, FDA approved clozapine with a blood monitoring requirement, but didn’t designate a specific approach.

FDA told Sandoz that offering Clozaril outside of the patient monitoring service could be deemed misbranding.4

Under the FDCA, Sandoz possessed the exclusive right to market clozapine until September 1994. But, trouble ensued when Sandoz required a specific blood monitoring service. Circa 1991, here is what the New York Times had to say:

Clozapine, a highly effective new treatment, promises relief for thousands of schizophrenics, and Federal administrators merit praise for insisting that all states make it available to the poor under Medicaid. It can save millions and reclaim lives.

Concerns remain that the drug's manufacturer, Sandoz Pharmaceuticals, is trying to profiteer from the desperation of mental patients and their families. But that no longer seems a compelling reason to deny patients the drug.

Psychiatrists say clozapine works wonders, often enabling hospital-bound patients to find jobs and lead nearly normal lives. It also promises new help for the homeless mentally ill, most of whom suffer from schizophrenia.

While patients on clozapine don't suffer a common side effect of other schizophrenia drugs, a small percentage are subject to a fatal blood disorder. For that reason, Sandoz originally sold the drug only to those who agreed to contract for blood monitoring with a company called Caremark.

The arrangement raised antitrust issues. Here is what former FTC Chairman Janet Steiger 1991 had to say:

Sandoz sold its drug, Clozaril, as part of a package which included monitoring and distribution services. Sandoz called this package the Clozaril Patient Management System ("CPMS"). While careful monitoring of patients using this drug is necessary to detect a possible fatal side-effect, institutional purchasers of the drug contended that they could ably and less expensively administer their own patient monitoring services. For example, the Veterans Administration estimated that it could save $20 million a year by providing these services itself.

Because Sandoz possesses under the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act the exclusive right to market clozapine in the United States until September 1994, the company was able to force purchasers to obtain the whole package if they wanted to obtain the drug. But, under our consent order, Sandoz agreed not to require purchase of the entire CPMS system, and overall it appears the price of clozapine therapy has decreased from the previous price of about $9,000 a year per patient.

The high price of clozapine package caused controversy. Critics called “the drug ‘a public rip-off’ and ‘a rich [person]’s drug for a poor [person]'s disease.’”5 Out of the $9,000 price tag, the cost for the drug represented only $500 per patient. Despite its promise and effectiveness, many Federal and state programs rejected covering the drug as too costly. A newspaper article from 1990 documents the outrage:

Sandoz has refused to itemize the costs of the system, prompting some to claim the company is concealing huge profits.

Some states want to pay only for the drug and not the management system, said Roy Praschil, executive director of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. But Sandoz charges only one price, $172, for the entire package.

Mental health advocacy groups criticize states for not making the drug available immediately through Medicaid. But they are also angered by reports that Sandoz sells clozapine in Europe for $30 per week.

"Sandoz and many states are holding the patients hostage," said Tom Posey, president of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. "It is unconscionable to think that a possibly greedy company and stingy states are blocking the most significant advance in anti-psychotic medication in 20 years."

Taylor says Sandoz is an ethical company. "We developed what we think is the most appropriate and ethical manner to distribute the drug," he said.

Tying

The above describes what the law calls a tie or tying. Because Sandoz had the exclusive right to sell clozapine, it had market power in the market for clozapine. To obtain clozapine, however, Sandoz forced purchasers to buy a broader package, the “Clozaril Patient Management System,” that included other segregable services such as patient tracking, blood drawing, distribution, and delivery. Sandoz then entered into an exclusive contract with Caremark to deliver these services and under the terms of the contract. Sandoz would provide the drug only if patients agreed to pay for weekly blood testing done exclusively by Caremark.

At the time, bundling a drug with medical services was a novel practice, and Sandoz claimed that the CPMS was the only reliable way to monitor for blood disorders.6 Sandoz claimed that these monitoring arrangements were necessary to protect it against malpractice lawsuits

Tying arrangements usually violate antitrust laws. They are usually bad for consumers. As the FTC explained in the consent order, Sandoz’s tying arrangement raised the price of clozapine and prevented others — such as private laboratories, the Veterans Administration, and state and local hospitals — from providing the related blood tests and necessary patient monitoring. The $9,000 for the CMPS system in 1991 is like $20,000 today in 2024.

Today, the clozapine case is the poster-child for tying, featured prominently on FTC’s website describing tying:

And, by the way, that was just the FTC litigation. There were also actions filed by 20+ State Attorney Generals and multiple class actions under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, both of which settled.

Conclusion

Clozipine is one of the first times FDA approved a drug with a distribution requirements, a precursor of the modern day REMS program. “No blood, No Drug” became a slogan Sandoz would trademark.

To summarize, as a legal matter, there wasn’t anything inherently wrong with a restricted distribution program. Rather, the antitrust issue arose from Sandoz forcing consumers to use its program.7 “The drug maker was the only producer of the medicine, but there were many companies capable of providing the blood-monitoring services to patients using the drug.”

Note: nearly all pharmaceuticals today are for-profit. This does not mean non-profit drug development is impossible. This quote from Rick Doblin’s recent letter is instructive:

In the event of FDA approval, rescheduling of the medical product by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) must, by law, take place within 90 days after approval, to be followed by state rescheduling. In addition to managing the FDA NDA process, Lykos is also building commercial capabilities to integrate MDMA-assisted therapy into the healthcare system, in the event of approval of the NDA by the FDA…

In addition to triumph and celebration, there is also failure and mourning mixed in with the creation of Lykos Therapeutics. My dream was to develop MDMA-assisted therapy entirely with philanthropic funds. That way, the for-profit MAPS Public Benefit Corporation would have remained wholly-owned by the nonprofit MAPS, my ideal corporate structure for the first-in-class psychedelic-assisted therapy potentially approved by FDA to be mainstreamed at a time in history when the world is on fire. Despite my best-sustained effort for several years, I failed to inspire enough philanthropists to donate the ever-increasing millions of dollars required to both obtain FDA approval and to build the infrastructure needed for patient access, especially since there were many newly created investment opportunities in the psychedelic ecosystem.

The claim is not that MAPS couldn’t get approval for MDMA with philanthropic dollars, but that it could not both get approval and build the infrastructure with philanthropic dollars. This distinction is important. The point isn’t that getting FDA approval with philanthropy is impossible, but that building the infrastructure needed for patient access made it impossible. Consider Harm Reduction Therapeutics, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit that sells its naloxone product at cost: $36 per twin pack available over-the-counter.

I suppose there’s an alternative world where MAPS got MDMA approved but didn’t build out the infrastructure itself. To borrow an idea from another, does anyone seriously believe that MDMA gets FDA-approval and then just sits in a warehouse? Most likely, the community and market would step in and find a way.

But not internationally. In some European countries, GHB is approved to treat alcoholism. The evidence is substantial.

I’ve been noodling about the following question for a while: Can the FDA approve an NDA for “assisted therapy”? It is an interesting legal question with far reaching implications related to federalism, FDA authority, and even the Orange Book.

Under 21 U.S.C. 355, “any person may file with the Secretary an application with respect to any drug subject to the provisions of subsection (a).” The term “drug,” in turn, means “(A) articles recognized in the official United States Pharmacopoeia… (B) articles intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease in man or other animals; and (C) articles (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals; and (D) articles intended for use as a component of any article specified in clause (A), (B), or (C).”

Based on this statutory definition and the plain meaning of article, I suppose one could say “MDMA assisted therapy” is an “article.” But, after applying ordinary tools of statutory construction, it is hard to see how this understanding of “drug” or “article” could prevail. It would render other uses of the terms “drug” throughout the FDCA to be mush. Moreover, courts have repeatedly explained that FDA’s jurisdiction extends to regulating products. E.g., FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 529 U.S. 120, 133 (2000). Take Brown & Williamson, which looked at the FDCA as a whole, and concluded that tobacco was not a “drug.” Consistent dictates that FDA doesn’t regulate the practice of medicine weighs against a notion that “drug” should be construed to include “therapy.”

What about the Orange Book? Do the patent listing provisions of 21 U.S.C. 355(b)(1) make sense if “drug” means “assisted therapy”? Alternatively, do any of the Orange Book provisions apply if an NDA is directed to “assisted therapy”?

Or, “combination products.” The regulatory definition is based on the combination of two or more regulated products, and psychotherapy is not an FDA regulated product. Indeed, the definition of “combination products” undermines the case that “drug” or “device” could encompass “therapy.” So does 21 CFR 201.57(c)(2)(i), which provides that “if the drug is used for an indication only in conjunction with a primary mode of therapy (e.g., diet, surgery, behavior changes, or some other drug)” labels must include “a statement that the drug is indicated as an adjunct to that mode of therapy.” The regulation distinguishes between a “drug” and a “therapy,” meaning “assisted therapy” cannot be a drug.

Very likely, in an APA action, a court could rule that approving psychedelic assisted therapies—as opposed to the more traditional approach of approving drugs indicated for use in therapy—is in excess of FDA’s statutory authority. The textual evidence indicating a “drug” cannot be “psychotherapy” is overwhelming, and approving therapy would mark a significant expansion of FDA’s regulatory authority, would intrude on the practice of medicine, would depart from FDA’s prior precedents, and would raise Tenth Amendment concerns. It might even raise First Amendment concerns because some courts have considered talk therapy to be protected speech. See King v. Governor of the State of New Jersey, 767 F.3d 216, 224–25 (3d Cir. 2014) (concluding that talk therapy qualifies for First Amendment protection).

Also, it defies common sense. When is the last time you heard someone use the phrase “anesthesia assisted-surgery”? On some level of abstraction, most if not all drugs could be rebranded to be an “assisted” what not.

As to REMS, as the FDA recently recognized, REMS is a program to ensure safety not effectiveness. And, while certain principles should be abided by to improve safety, I have seen little evidence that as a matter of unreasonable safety psychedelics must be administered according to a particular psychedelic protocol. To quote FDA’s Tiffany Farchione, “If psychotherapy, or a specific treatment setting, is required to ensure the product is effective, then REMS isn’t going to help with that.” This is especially true considering the inherent competition issues described above.

Whether FDA should approve “assisted therapies” or the like raises broader, far reaching, and potentially more dangerous systemic consequences beyond psychedelic assisted therapies. For example, should FDA be regulating and evaluating the safety and effectiveness of reproductive assisted therapy, such as IVF, as opposed to the products that may be used in such therapies? Looking at the system as a whole, it may not be a good idea—indeed, it may be a profoundly bad idea—to cross the Rubicon of having the federal government regulate “assisted therapies,” which has traditionally been the domain of medical practice and of the States. Historically, FDA has approved drugs to be used in therapy or procedures, not the therapy associated with the drug. For example, GnRH agonists were approved by FDA for use in IVF in 1987. What about abortion procedures? Gender affirmation or, alternatively, transition therapies? Addiction counseling? And, if you invite the federal government into the practice of medicine more traditionally regulated by the states, you invite the consequences of the whims of changing administrations.

In short, anyone embracing the prospect of the FDA regulating psychedelic assisted therapy—as opposed to the drugs themselves—should think carefully about what that means more broadly. Setting precedent by inviting federal regulation into the practice of medicine could have far reaching consequences, and perhaps not good ones under an administration of the opposite political party. And, similar to how the patent system operates, more regulation could result in retarded innovation.

There isn’t a serious dispute, however, that FDA could approve psychedelics with labels that the medicine be administered with therapy.

Mark A. Hurwitz, Bundling Patented Drugs and Medical Services: An Antitrust Analysis, 91 Colum. L. Rev. 1188, 1191 (1991)

Hurwitz at 1189–90 (1991).

Hurwitz at 1190.

Interestingly, today, some argue that the need for the clozapine REMS is questionable and hurts patients. Clozapine is an inexpensive generic drug, but rarely prescribed. But while clozapine is a “miracle drug” for treatment resistant schizophrenia, the REMS “is a nightmare.” From the linked article:

O’Dell said that aside from many administrative problems with the REMS, the requirements for lifelong monitoring for neutropenia are unjustified. “It just doesn’t make sense when you look at the actual risk of neutropenia,” O’Dell told Psychiatric News. “It’s a lot lower than we used to think it was, is comparable to other antipsychotics, and neutropenia tends to happen in the first year of treatment. There is very little justification for how the REMS program is currently set up, and in my view it’s questionable whether there is any justification for a REMS.”

Neutropenia is a possible side effect, but is relatively rare, occurring in less than a quarter of a percent of users. Some modern research from controlled trials does “not support the belief that clozapine has a stronger association with neutropenia than other antipsychotic medications” and “implies that either all antipsychotic drugs should be subjected to hematological monitoring or monitoring isolated to clozapine is not justified.” The clozapine REMS in its current form, even if justified in some capacity, likely overshoots.

And, the REMS has not been harmless. Technical difficulties with the REMS in November 2021 became so severe, FDA had to suspend some requirements.

Following advocacy and pressure by the American Psychiatric Association and practitioner associations, FDA is reassessing the REMS, including assessing whether the REMS is still necessary. As this letter explains: