When Patents Met Regulations, which is unlocked, provides background to both parts of this essay. Part one is here.

Public Service Announcement: I am affirmatively seeking speaking gigs/panels/podcasts/etc. in 2023 to talk about the intersection of IP law, Hatch-Waxman, and regulations.1 I believe this is the most-important-least-talked-about legal issue in psychedelic medicine. If anyone has suggestions, recommendations, or opportunities, please let me know. Here is my contact.

Part 2: Avadel Pharmaceuticals

Xyrem’s Problem

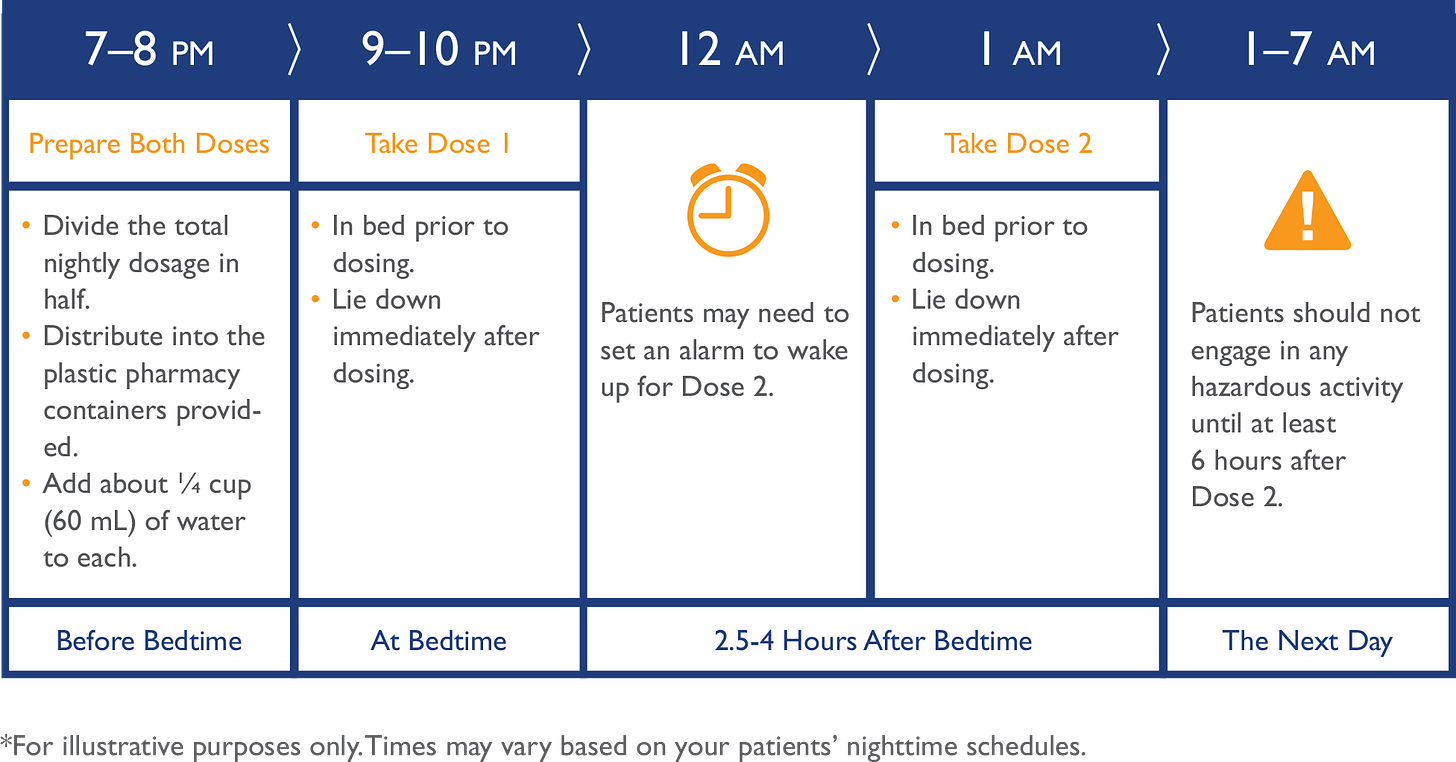

Xyrem isn’t a perfect drug. Far from it. Xyrem treats symptoms associated with narcolepsy. But its dosing regimen requires a patient take an oral solution divided into two doses. The patient takes the two doses once before bed and a second in the middle of the night. This requires setting an alarm clock to forcefully awaken the patient in the middle of the night. If one takes Xyrem according to its label, getting a “full” eight-hours of uninterrupted sleep is impossible.

Avadel Pharmaceuticals

Enter Avadel. Founded in France in 1990 as Flamel Technologies SA and now headquartered in Ireland, Avadel is a specialty pharma company focused on delivery technologies.

Sometime after the approval of Xyrem, Avadel a crazy idea: maybe waking up to re-dose isn’t an optimal way to treat a sleep disorder. So, using its proprietary drug delivery technology, Avadel built a better mousetrap. After almost a decade and a 100 million dollars, Avadel unveiled FT-218—a once-at-bedtime extended release sodium oxybate product:

If what Avadel claims is true, FT-218—brand name Lumryz—is a life-changing innovation. Lumryz is also protected by IP, including patents.

Also, in early 2018, Avadel obtained an Orphan Drug Designation.

FDA Tentatively Approves Lumryz

In March 2020, Avadel completed REST-ON—a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 trial to assess the safety/efficacy Lumryz in narcolepsy patients. The trial yielded positive data. So, shortly after in December 2020, Avadel submitted submitted an New Drug Application (NDA) to FDA. In February 2021, FDA accepted the NDA and assigned a target action date of October 15, 2021.

Because Lumryz contains the same active ingredient as Xyrem (sodium oxybate), Avadel made a 505(b)(2) submission. The (b)(2) pathway is different from the pathways used with new drugs or generics; it is a hybrid. It can be used in a variety of circumstances. FDA lists 10 examples of applications that could be accepted under (b)(2). If you want to read more about (b)(2)s, FDA has a guidance doc here. Like a generic drug applicant, (b)(2) applicants do not need to produce all the safety/efficacy data from scratch. They need only produce some data, including whatever information is needed to support the modifications.

So, for example, assume MAPS MDMA is approved. Perhaps some for-profit joint comes along and wants to reformulate MDMA in a way that would improve upon it. Once the MAPS data exclusivity period expires, a company might be able to rely on MAPS data in a (b)(2) application. Absent any patents outliving the data exclusivity period, if the (b)(2) product were approved, it would compete with MAPS MDMA.

But here, Jazz does have patents. As discussed in Part 1, a (b)(2) application requires companies certify that any Orange Book patents are not infringed or are invalid. Avadel acknowledged a REMS would be needed for Lumryz, but it claims it developed a distribution system different from the Jazz system. So, it stated in the certification that the REMS patent did not apply.

In May 2021, Jazz disagreed and sued alleging: (1) the FDA will not approve Lumryz without a REMS; (2) the FDA-approved REMS for sodium oxybate are covered by the ’963 patent; and therefore (3) the REMS for Lumryz must include protections required in the currently-approved REMS for sodium oxybate products that are covered by the ’963 patent. The FDA then granted “tentative approval” to Lumryz, subject to a REMS. This means Lumryz is ready to go to market: it meets all required quality, safety, and efficacy standards necessary for final approval.

The hang-up is the REMS patent in FDA’s Orange Book.

Jazz v. Avadel

Okay, the case—and what the FTC brief calls “Orange Book” abuse. Let’s first re-set the stage by briefly reintroducing our key players.

1. GHB/Xyrem. Jazz makes Xyrem, a drug approved to treat cataplexy associated with narcolepsy. The active ingredient is GHB. When not in an FDA approved product, GHB is in Schedule I. Otherwise, Schedule III.

2. The REMS Patent. Because of its abuse liability, the FDA approved Xyrem with REMS program. The REMS program proposed by Jazz and approved by the FDA requires a computerized distribution system. Jazz has a patent on aspects of the process. U.S. Patent No. 8,731,963 claims a “computer-implemented system for treatment of a narcoleptic patient with a prescription drug that has a potential for misuse, abuse or diversion.”

Recall in the 2018 case, Jazz Pharms., Inc. v. Amneal Pharms., LLC, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Patent Office’s decision to cancel most claims in the patent family to which the REMS patent belongs, including several in the REMS patent itself. A few claims survived.

3. Avadel/Lumryz. Avadel develops a competing sodium oxybate product called Lumryz. Its edge is that it requires just once-nightly treatment.

With Lumryz encroaching on Xyrem’s turf, Jazz did what pharma companies with patents do: it sued. But again, Jazz is not a typical Hatch-Waxman suit where brand sues generic. Here, Avadel (competitor) has its own a novel sodium oxybate drug, its own patents, and an innovative product. We end up in Hatch-Waxman land because Avadel used the (b)(2) pathway.

What is a Delisting Claim Anyway?

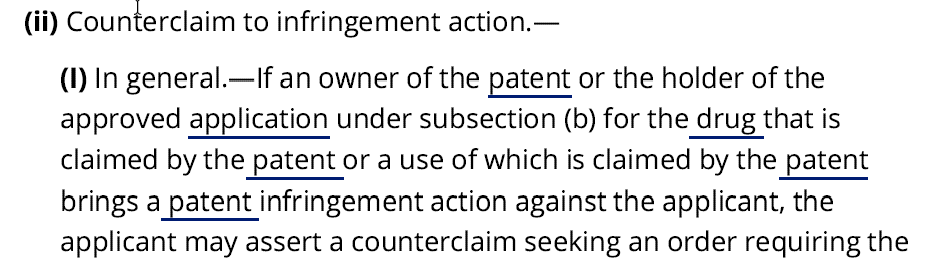

At the heart of the Jazz v. Avadel REMS patent dispute is a delisting claim.

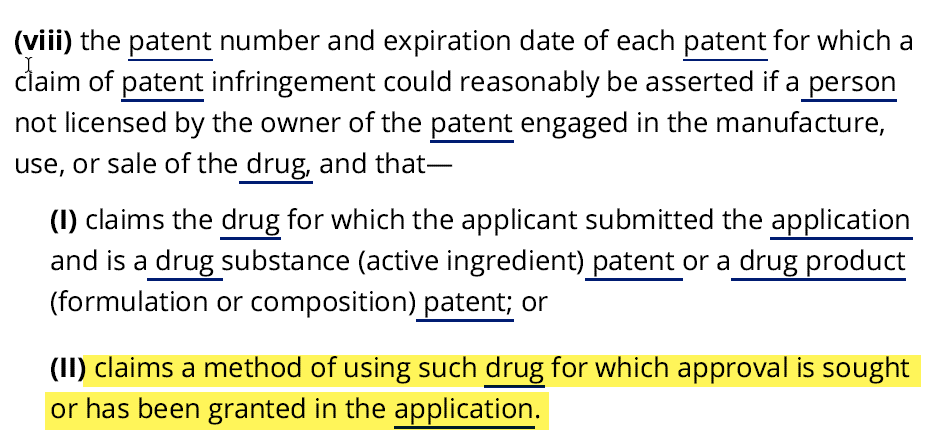

As discussed in Part 1, FDA regulations require NDA holders to submit patent information on composition and method-of-use patents that claim “the drug or a method of using the drug that is the subject of the NDA.”2 Those submissions go into the Orange Book. This listing gives the NDA holder the right to suspend the regulatory approval process of potential competition as a matter of statutory right merely by initiating a patent infringement action against a competitor.

Importantly, the FDA does not police Orange Book listings. Per a Federal Register listing in 1994, FDA does not do so because it did not have expertise on patent law issues. In 2003, in response to comments about the need for a method for to challenge patent listings or for de-listing patents in the Orange Book, FDA repeated this view: “the courts are the appropriate mechanism for the resolution of disputes about the scope and validity of patents and "have the experience, expertise, and authority to address complex and important issues of patent law." The agency further explained that the short statutory time frames "do not contemplate a substantive agency review of the scope of the patent and its application to the approved drug product."3

Given the power of regulatory stays and no regulatory supervision, it should come as no surprise that pharma companies began improperly listing patents. Here is the 129-page 2002 FTC report. Or, a visual representation of the situation:

Worse, no private cause of action existed to delist patents. One company tried. “Bristol [Meyers] avoided competition by abusing federal regulations in order to block generic entry.” Mylan sought an injunction to delist the improperly listed patent. The Federal Circuit Court of Appeals held that Hatch-Waxman contained no private cause of action to delist patents.

Enter Congress. Responding to Mylan’s failed lawsuit, Congress fashioned a remedy—a delisting counterclaim—allowing private litigants to delist an improperly listed Orange Book if sued for infringement under Hatch-Waxman.4 The statute states that a party asserting a delisting claim, like Avadel, is entitled to relief if it can show that the listed patent “does not claim either—(aa) the drug for which the application was approved; or (bb) an approved method of using the drug.” Note. however, that the statute does not allow a party to go to court and affirmatively assert a claim. A delisting claim can only be asserted as a counterclaim in an existing action.5

Avadel Reaches for a Quick Win

Out of the gate, in July 2021, Avadel moved for judgment on the pleadings on its “delisting” claim. Obtaining judgment on the pleadings in litigation is rare. It occurs only when based on the initial filings in a case, there are no disputed material facts.

Avadel had a good claim, however. The REMS patent, on its face, claims a computerized system. It does not claim a “drug substance,” “a drug product,” or “a method of using a drug” as the statute requires. So, said Avadel, the patent was improperly listed.

But the Court did not agree—not initially. It declared Avadel’s opening shot unripe or premature: “Defendants’ arguments depend in no small part on claim construction and the question of whether the claimed ‘system’ includes methods of using the approved product.”

Time to put patent law hats on.

“Claim construction” (also called Markman) is a term of art in patent law. And it is extremely important. Claim construction is the process by which a court or administrative body interprets the scope and meaning of a patent claim.

Parties usually disagree on the meaning of certain words or phrases in claims. Whether a product or process infringes often hinges on the meaning of one or more words in the claim. When these disputes arise, it is the duty of the court or administrative body to resolve them. They do so by analyzing the meaning of the words in the patent’s claims, specification, and file history. It is a sadistic exercise enjoyed only by grammar/language nerds and those getting paid big bucks.

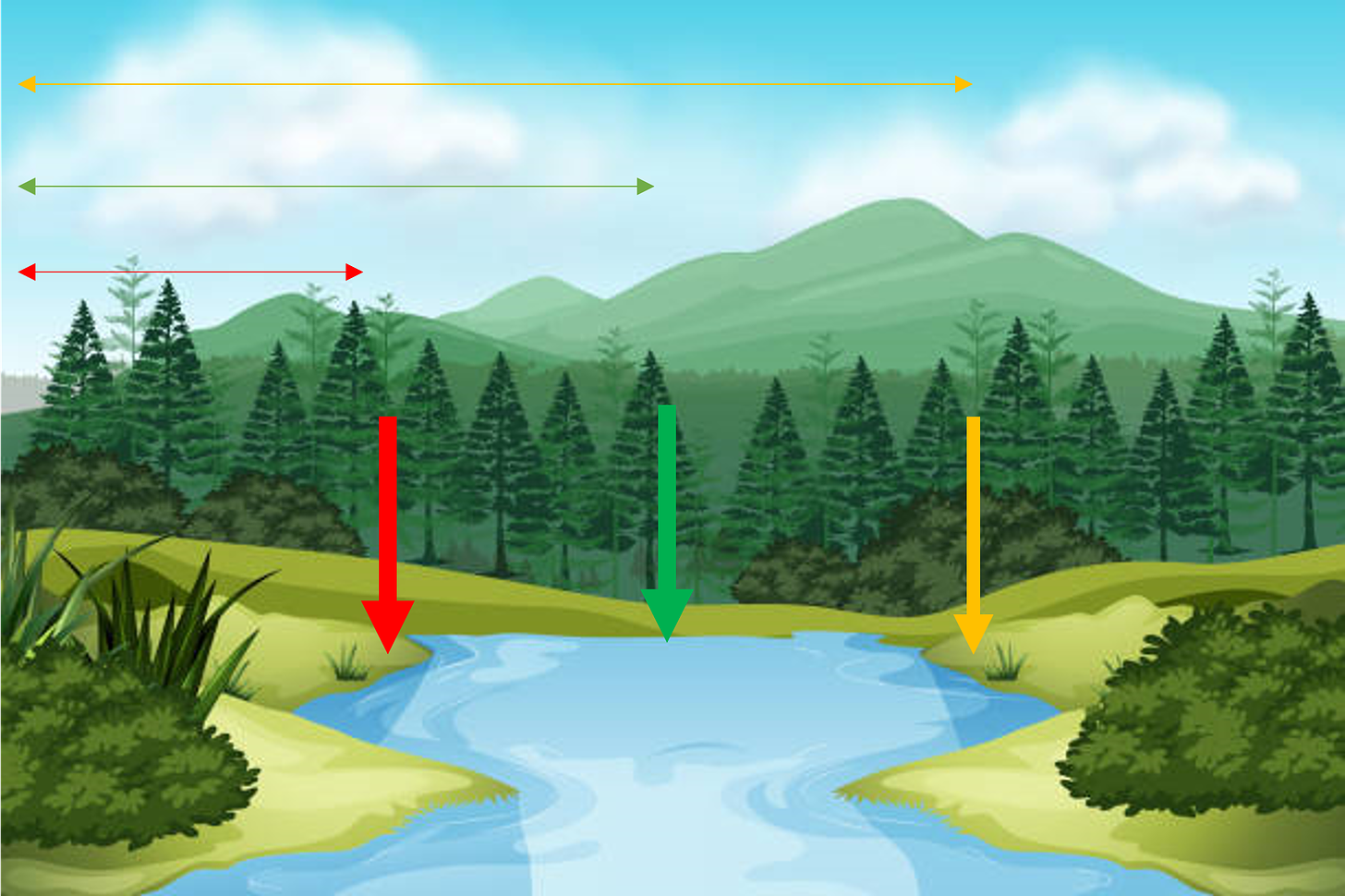

By way of a contrived example, let me illustrate why this is hugely important and often dispositive. Say you have a plot of land. Your land has fence posts. Those fence posts demarcate the metes-and-bounds of your land. Now say you get into a dispute with your neighbor. In a nearby stream, your neighbor likes to swim naked. You don’t like that. You want him off your land. You tell him he is trespassing. Who wins?

Well, let’s look at your deed. Your deed says your land goes “to the stream.” But what does “to the stream” mean. Which side of the stream? The far side (yellow)…or the near side (red)? Or is it in the middle (green)? In other words, does “to the stream” include the stream and if so, how much of it?6

This matters a great deal. Indeed, the whole dispute rides on the answer. Your neighbor is either trespassing or not, depending on how one construes the claim. To figure out the right construction, a court would look at the language of the deed itself (claim), other text in the deed describing the land (specification), and if available, any relevant discussion about the stream in the original negotiation over awarding the land (prosecution history).

This type of dispute is central to nearly every patent case and patent law generally. Entire treatises have been written about claim construction. If you eager to earn extra credit, take a look at this case where the parties disputed the meaning of the word “baffles.” And if you are feeling really randy, have a go at this classic case where the parties disputed the meaning of “only if.”

The relevant takeaway for today, however, is much simpler: this linguistic dance takes time. Parties file lengthy briefs with appendices over periods of months, followed by a court hearing, waiting, and a court opinion. So when the court concluded that ruling on a delisting claim early in the case would be improper because claim construction had yet to occur, it deferred ruling on Avadel’s July 2021 motion. The court kicked the can down the road—all the while Jazz enjoyed more exclusivity. Jazz’s Xyrem is a $1.5 billion dollar drug. For those doing back-of-the-envelope math at home, each day of delay can be as much as $4+ million.

[This raises an important point/meta-point about these essays. They are becoming increasingly detailed and complex, and as a result, they take longer to write. This may lose some readers, but for the time being, there is a reason for this. To understand and accurately describe how these complex legal systems work and their issues, one must get into the details and into the primary sources. That is where law is ultimately made: arguments and tactics in courtrooms, briefs, opinions, and other legal materials.

Whether or not the court was correct to defer ruling on the delisting issue following full briefing on claim construction, the court severely compromised the claim by deferring ruling on the motion. In pharma, time is of the essence. A delisting claim that, as a practical matter, can only be asserted as a counterclaim and never be timely adjudicated early in a case while an automatic regulatory stay runs is no real remedy at all. That is the main takeaway, and it rests in the details of how patent litigation works in the real world.]

Avadel Reurges the Motion

In June 2022, Avadel re-urged its motion for judgment on the pleadings after the parties “solidified their claim construction positions.” Even under Jazz’s view of the patent, Avadel argued, the listing was improper. Jazz viewed the ’963 patent as covering a method to safely distribute GHB, which was not a method of using GHB. Distributing an drug product, Avadel contends, is not the same as using the drug product. This seems self-evident, no? Avadel also asserted that Jazz was using Hatch-Waxman Act and REMS to improperly block or delay an improved, once-nightly product from reaching patients.

Jazz argued Avadel’s motion remained premature, i.e., more delay.

In early September, the case got a new judge, Judge Gregory Williams. Avadel went back to the well and argued for expedited consideration of its delisting motion. I’ll quote from Avadel’s redacted brief (emphasis mine, lightly edited):

Avadel has spent years and hundreds of millions of dollars developing a novel drug called LUMRYZ, which allows narcoleptic patients to take a single dose of oxybate at bedtime to help them fall asleep and stay asleep throughout the night. Existing oxybate treatments for narcolepsy, such as Jazz’s Xyrem product, require patients to take one dose at bedtime and set an alarm to forcefully awaken partway through the night to take a second dose. As the first once-nightly oxybate product, LUMRYZ stands to eliminate the burden and inherent safety and compliance problems of twice-nightly oxybate products like Xyrem, and address patient demand for a narcolepsy treatment that allows for an uninterrupted night’s sleep.

…

Indeed, public stock analyst reports recognize the obvious: delay of approval for LUMRYZ uniquely benefits Jazz. After spending hundreds of millions of dollars to develop LUMRYZ, Avadel must continue with no incoming revenue from LUMRYZ, its only product. The continued delay in Avadel’s market launch has already forced the company to engage in drastic cost-cutting measures, including terminating nearly 50 percent of its work force in June of 2022.

As explained above, individuals suffering from narcolepsy are limited to Jazz’s oxybate products, which require patients to set alarms and forcefully awaken in the middle of the night to take medication for treatment of their sleep disorder. This treatment plan for patients already suffering from disrupted sleep is counterproductive and wrought with safety concerns, and many patients struggle to comply with this twice-nightly dosing requirement. Indeed, some narcolepsy patients must forgo treatment with oxybate because they cannot comply or consider it unsafe to do so—among other issues, the twice-nightly regimen requires leaving the second dose of this controlled substance with abuse potential sitting on a nightstand for several hours, where children or roommates can access it. LUMRYZ provides a once-nightly oxybate treatment that avoids the difficulties of Jazz’s twice-nightly dosing regime and provides patients with a much-needed improved narcolepsy treatment that allows for a full nights’ sleep.

Meanwhile, in a different federal court, Avadel filed a second lawsuit. There, Avadel claimed the FDA violated the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) by (1) requiring Avadel to submit a Patent Certification violated and (2) unreasonably delaying approval of Avadel. Avadel sought a court order releasing it from the obligation to file a Patent Certification and an order requiring FDA to rule on its NDA for Lumryz.

Jazz then intervened as a third-party to oppose Avadel. Long story short, in early November 2022, the DC district court opined that Avadel could not get APA relief because it had adequate relief in the Delaware case.7

The FTC Brief and the Court’s Order

The FTC brief takes no position on the REMS patent itself. But it does answer the question of whether patents that claim drug distribution systems—such as a REMS-mandated distribution system—meet the Orange Book’s listing criteria. Succinctly stated, the FTC said: no. “A REMS distribution system cannot plausibly be considered a ‘method of using a drug’”8 Per the FTC, “the Orange Book is not intended to be a repository for every patent relating to a brand product.”

The FTC brief further notes that Orange Book abuse isn’t uncommon. Pages 14-15 and footnote 23 of the brief explain how, before the 2003 Amendments, brand manufacturers would exploit the Orange Book in two ways: (1) by repeatedly listing new patents and obtaining additional 30-month stays and (2) exploiting the fact that the law originally had no procedure to remove listed patents from the Orange Book. According to the FTC, some drug companies would list new patents on the eve of a competitor’s approval to block competition.

The FTC brief makes another noteworthy point about REMS. When Congress enacted the statute establishing REMS in 2007, it explicitly prohibited brand sponsors from using REMS requirements to “block or delay” ANDA and (b)(2) approval:

No holder of an approved covered application shall use any element to assure safe use required by the Secretary under this subsection to block or delay approval of an application under section 355(b)(2) or (j) of this title or to prevent application of such element under subsection (i)(1)(B) to a drug that is the subject of an abbreviated new drug application.

Thus, the FTC argued that improperly listing a REMS distribution patent in the Orange Book to obtain a regulatory stay based on that listing “may constitute a misuse of the REMS to ‘block or delay’ the approval of ANDA or 505(b)(2) products in violation of the FDAAA.”9

Shortly after the FTC filed its brief, the court granted judgment on the pleadings and ordered Jazz to delist the REMS patent. Succinctly stated, the court concluded that the REMS patent neither claims a drug nor “an approved method of using the drug" because the claims of '963 patent are directed to systems, not methods.

The Appeal

Not surprisingly, Jazz took an immediate appeal.10 The first order of business was Jazz requesting a stay of the district court's injunction, which was granted. The fact that the Federal Circuit granted a stay means very little about the merits. But it did keep the regulatory stay in place for a few more months.

The Opening Brief

The party appealing the decision “below” (i.e., trial court) files the opening brief. Jazz frames the question on appeal as follows: “This appeal concerns whether a patent that claims an FDA approved condition of use for a pioneer drug should be listed in the Orange Book.”

Strange way to frame the case. The statutory question isn’t whether the patent claims a condition of using a drug but rather a “method of using the drug.”

Framed in this manner, the Jazz brief wins only if a condition of using a drug is the same thing as a method of using a drug. Jazz then turns to the interpretive question: what does “method of using a drug” mean. Jazz claims the district court erred by treating the phrase as presenting a question of patent-law as opposed to Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) law. If “method” hinges on patent law, then Jazz is out of luck since there is no reasonable dispute that the REMS patent doesn’t claim method steps (it claims a system).

But even assuming Jazz is correct and the interpretive exercise is through the lens FDCA law, Jazz should still lose. For example, the regulations have a section on method-of-use patents that makes it clear that “condition of use” is different from a method-of-use patent.

Notably, conditions of use are described elsewhere in the same section:

As the FTC very persuasively argued in its amicus brief, “conditions of use” plainly means conditions on using the drug, not conditions on distributing or prescribing the drug. A condition of FDA approval for a drug is different from a condition of using a drug. Even under FDA law and regulations, there is no doubt (in my mind) that a threshold requirement to list a patent as a “method of using” a drug is that the patent claim a method of some kind—something the REMS patent does not. It claims a computerized system.

The Jazz brief makes two other arguments: (1) even if the REMS patent does not claim a method of using a drug, it was properly listed in the first instance and so it shouldn’t be delisted and (2) the claim construction entered by the district court was wrong. Neither is persuasive.

Jazz argues that the listing statute is silent as to whether other categories of patents could be listed, i.e., those listed are “not exhaustive” and when Jazz made its initial listing, the listing was proper. So, according to Jazz, the delisting statute “cannot be understood to empower courts to order the delisting of patents that are properly listed.” In other words, a delisting claim cannot apply retroactively to a patent that was properly listed.

The second argument fills just four pages. It argues that claims to “system” are, in fact, methods. According to Jazz, the plain meaning of “system” is a “formulated, regular, or special method or plan of procedure.”

The Response Brief

The Response Brief refutes these arguments. In my view, persuasively.

First, Avadel argues that the delisting statute calls for district courts to undertake claim construction to determine whether a patent claims a drug or method of using a drug. This is so, according to Avadel, because the delisting statute presents questions about what a patent does or does not claim. Thus, “method” carries the meaning is has in patent law. Avadel cites multiple cases involving the Orange Book statute to support its point.

Avadel also argues that Jazz forfeited this argument. With some exceptions, a party forfeits arguments on appeal that they do not make below. According to Avadel, Jazz never argued its FDCA vs. patent law argument below. Rather, it insisted that Avadel’s motion for judgment on the pleadings could not be resolved because claim construction was required, procuring additional delay.

Second, Avadel persuasively argues that Jazz’s argument fails on its own terms, aggressively quoting the FTC Brief:

Even assuming that the ’963 patent claims a “method” in some ordinary-language sense, it does not claim a method of use. Per the FTC, a “REMS distribution system cannot plausibly be considered a ‘method of using a drug,’” because REMS distribution systems concern ways of distributing drugs; they do not concern methods of use. …

A REMS distribution system is “a condition of FDA approval for certain drugs. But that does not make it a condition of the drug’s use.”

Third, Avadel argues that the delisting statute, enacted in 2003, allowed Avadel to raise a counterclaim to delist any patent that did not claim either a “drug” or a “method of using” a drug. Whether Jazz the REMS patent could have been permissively listed in 2014 according to FDA regulations was thus “not relevant.” The delisting statute’s plain language controls. Avadel also argues that the REMS patent was not properly listed in any event.

Last, the Response Brief, notes that the Opening Brief does not meaningfully contest the correctness of the district court’s construction. And how could it? As the Response Brief notes every claim recites a “computer-implemented system” with computer components. The REMS patent claims do not include any method steps.

To conclude:

For over a year now, Jazz has managed keep Avadel’s superior, one-dose regimen off the market, to the great detriment of narcolepsy patients (who are left with only Jazz’s two-dose sleep-disrupting option)—based on a patent that is not remotely a drug or a “method of using” a drug. Congress provided a delisting mechanism for precisely such situations. The district court got it right.

The Reply Brief

The Reply Brief largely retreads old ground. For example, it asserts that a “REMS falls comfortably within the ordinary meaning of ‘an approved method of using [a] drug,’” and that “the elements of a REMS clearly constitute approved conditions of use” with more linguistic chicanery:

A REMS is an “approved method of using [a] drug” under the plain meaning of the delisting statute. As the Supreme Court has explained, “use” is an “expansive” term that “sweeps broadly.” Smith v. United States, 508 U.S. 223, 229 (1993). For example, the phrase “uses a firearm” clearly covers “using a firearm as a weapon.” Id. at 230, 236 (citation omitted). But that doesn’t mean that the phrase “excludes any other use.” Id. at 230. To the contrary: “it is both reasonable and normal” to say that a person “uses” a gun by bartering it for contraband. Id. The same linguistic principles apply here. While “the example of ‘use’ that most immediately comes to mind” might be administering a drug to a patient, that “does not preclude us from recognizing that there are other ‘uses’ that qualify as well.” Id. “[O]ne can use a [drug] in a number of ways,” id.—including by “deploy[ing]” it through a REMS, The New Oxford American Dictionary 1853 (2005)(“use” means “take, hold, or deploy (something) as a means of accomplishing a purpose”).

Had Congress meant to limit the phrase “approved method of using [a] drug” to just how the drug is administered to a patient, it could have said so. In fact, Congress employed just such language elsewhere in section 505. Take the provision governing abbreviated new drug applications, where Congress required applicants to report the effects of a drug “when administered to patients.” 21 U.S.C.

§ 355(j)(2)(A)(iv) (emphasis added). Congress chose different language in the delisting provision—forgoing narrower options in favor of the broad phrase “approved method of using [a] drug.”

The Reply brief does make one point worth considering. Congress and FDA have entertained calls to exclude REMS patents from the Orange Book since 2019. But no proposal has been enacted. The existence of these proposals, says Jazz, presupposes that REMS patents are properly listed in the Orange Book. FDA itself has acknowledged on the existence of REMS patents as well, never stating that these patents are ineligible. For example, in this FDA Report to Congress in response to the Orange Book transparency act:

FDA is aware that some NDA holders have obtained patents claiming the way one or more of their REMS requirements have been implemented and that this can impact the ability of a prospective generic applicant to form a single, shared system with the NDA holder. The prospect of NDA holders obtaining patents for REMS was also contemplated by Congress in the FDAAA…

Thus, Jazz argues that Avadel seeks “legislation-by-litigation.”

The Amicus Brief

Last, the Public Interest Patent Law Institute, Professor Robin Feldman, Eliana Bookbinder, Brian Mahn, and the Niskanen Center filed an amicus brief. Bookbinder and Mahn are narcolepsy patients that take Xyrem or Xywav and are “personally familiar with the logistical difficulties associated with taking Xyrem and Xywav and support the entry of new products.” And their brief repeats many of points I have tried to emphasize throughout: Lumryz improves on Xyrem by addressing its main twice a night drawback. “Once-nightly Lumryz eliminates patients’ need to rouse themselves from a drug-induced sleep in order to take a second dose.”

For those interested in the practice of law, this a very effective amicus brief. Amicus briefs often repeat points advanced by the parties. This can be effective, but usually briefing by parties on significant issues in important cases is good enough. What is often more helpful and impactful is to understand the real-world impact of a particular policy or direction.

[Second PSA: I’m an okay lawyer-writer and available for amicus work. I make less typos on the clock, too.]

This aspect of the brief is superb. It humanizes a technical law case about statutory interpretation and whatnot, making the abstract concrete and the stakes real. The whole brief is here, but I’m going to copy-paste several paragraphs to illustrate how this can be done. This isn’t just good briefing; it is good show-not-tell writing:

Taking Xyrem’s second dose around four hours after taking the first one means having to wake up while still under the influence of the first dose. The most obvious problem is that having been knocked out by the first dose, patients are often unable to wake for their alarms; patients reported setting multiple blaring alarms, often unsuccessfully, and relying on spouses and family members to wake them up. One patient reported that even after two years of using Xyrem, they miss their second dose about once a week.

If a patient does not wake up for the second dose, they may then wake up after about five or six hours of sleep. This creates a dilemma for patients. The patient can skip their second dose and suffer the symptoms of narcolepsy resulting from lack of sleep. Missing the second dose means, in the words of one patient “wak[ing] up tired, achey, [and in a] bad mood.” Missing the second dose can also lead to rapid-onset drowsiness and cataplexy attacks—the sudden onset of “weakness and a loss of voluntary muscle control.”

Alternatively, patients who have not woken up on schedule can take their second dose late, forcing them to oversleep. Whether or not the patient successfully wakes up and times their dosage correctly, a second problem emerges: patients are often groggy and disoriented—in no condition to measure out a precise volume of the liquid Xyrem formulation—meaning that the second-dose routine must be carefully orchestrated in advance. One patient measured out the second dose before bed but feared that the family pets might knock over the container; another reported receiving a concussion from falling over in the process of taking the second dose. Another patient reported falling asleep in the bathroom when going to take the second dose.

Even worse is when a patient wakes up early, as can happen when the first dose is not titrated precisely or the patient’s daytime activities cause a change in sleep patterns. Ideally, the patient realizes the error and is subjected to staying awake for hours until it is the right time to take the second dose. But being half-asleep in the middle of the night, some patients reported not realizing what time it was and taking the second dose early, effectively overdosing on Xyrem. One patient recalled realizing they had taken the second dose early, and panickedly tried to monitor for overdose symptoms by staying awake while on the double-dose of sleep medication.

…

Families of patients bear an immense burden. One patient relied on their parents to wake them up for their second dose (alarms did not work for them); the patient said they were immensely thankful to have family around to help but felt bad for making them wake up every night. Marriages have ended in divorce and students could not find roommates, we were told, because of the disruptive nightly second-dose routine. One patient wondered how a Xyrem patient could ever have children, as the drug’s strict schedule regimen would seem incompatible with the unpredictable midnight needs of infants and toddlers.

Patients’ careers and education also often suffered. Xyrem patients face more than the general inconveniences associated with oversleeping: if they are still experiencing the effects of Xyrem when they wake up it is unsafe to drive a car to get to work or school. Delayed second doses made patients late for school or work. One patient we talked to was a college student at the time they started taking Xyrem and reported not being able to enroll in morning courses because they might miss class due to a delayed second dose. One patient lost their job, another contemplated dropping out of school, and third could barely find time to do homework.

In sum, this isn’t (or shouldn’t be) a game. But guess what? It is.

Conclusion

Jazz is an immensely important legal case and not just because it has concrete implications for narcolepsy patients. Jazz is the type of case that could shape the future of pharma and psychedelic medicine—at least of the FDA-approved variety.

Take psilocybin. Like GHB, psilocybin is an old, off-patent compound. Very likely, DEA will reschedule an approved drug product containing psilocybin. FDA will require REMS. Patenting REMS or something ancillary could be a way to erect lasting artificial property rights where, perhaps, there should be none.

One more thing. Maybe you think patent law or the patent system is the culprit here and pharma companies are the enemy. I beg you, look harder. That assessment, in my view, misses at least half the picture.

Avadel, a pharma company, appears to have a truly innovative product. This product may significantly improve the life of those who take it. And no doubt, it invested hundreds of millions of dollars on R&D based on the expectation that a patent and IP rights would help it recoup the investment on the backend.

The big bad in this case isn’t patents or pharma, but the regulatory scheme. Specifically, the way the regulatory scheme intersects with patents and the behaviors that cocktail incentivizes. The reason Jazz can use a few surviving claims from one patent in a mostly invalidated family to block a competitor is the regulatory scheme. And it can do that merely by asserting a claim, as opposed to proving a claim. That assertion can be weak—implausible, even—and buying delay.

In my view, the REMS patent is almost a sidekick, which in the absence of the regulatory scheme, would be a worthless appendage.11

I generally do not solicit gigs or submit speaking proposals, but I accept invites. I can say most of what I want on here, reach the same audience + more, and have that message be more permanent and accessible to thousands of subscribers/readers without worrying about placating/offending/pleasing certain cliques or conference organizers, like this guy. Also, I’m starting to question the value of these gatherings. Seeing people is nice. But the substance of these conferences is getting redundant and largely boils down to the same people saying the same things to each other. I’m not sure attending more than a handful is that productive. But as I state above, I am affirmatively interested in speaking about the issues described in this and related essays.

The Orange Book Transparency Act of 2020 made a number of statutory amendments to the Hatch-Waxman framework, largely codifying in statute existing FDA regulations.

There isn’t a tsunami of Orange Book listings. A small contingent of government attorneys paid at a GS-14 or GS-15—less than $1 million a year in expenditures—could likely review the propriety of Orange Book listings as they come in. As Jazz v. Avadel and other cases illustrate, just one improper listing can cost consumers billions of dollars and access to innovative treatments.

Which again proves the value of litigation even when it “fails.” Court cases can shine light on an issue and provide a vehicle for Congress to fix it, often better than research.

In the law weeds: the statute provides a cause of action only as a counterclaim. As a result, a delisting counterclaim cannot be the basis for filing a lawsuit. A prospective competitor must wait until it is sued before it can respond with a delisting claim. As Jazz v. Avadel illustrates, this is not ideal. Litigating a delisting counterclaim can take years between the trial court and an appeal. Congress could fix this by allowing a preemptive delisting claim.

In a vacuum, the plain and ordinary meaning of “to the stream” would suggest up to but not including the stream. Nonetheless, context could suggest a different meaning.

Law weeds (again): The court held that the ongoing Delaware proceedings provided “adequate alternative relief.” As discussed above, however, that relief is only available after a company such as Avadel is sued by the Orange Book patent holder. The APA authorizes judicial review only when a plaintiff has no other “adequate remedy in a court.” Here, as the DC court goes on to say, Congress created an “independent cause of action.” But as the court recognizes, all Congress did was create a conditional cause of action.

Emphasis mine. In my view, the FTC’s use of the word “plausibly” is very significant; and it could be a hook into an antitrust suit against Jazz.

More law weeds: I agree, and I wonder whether, separate from the delisting claim—a violation of the FDAA renders the patent unenforceable under an equitable doctrine.

In most cases, a party has to wait until final judgment to appeal. Here, however, because of the injunction, an interlocutory appeal was available. 28 U.S.C. § 1292(c)(1).

Full disclosure: I have a small position in Avadel because, having read the briefs, I'm betting it wins.