There is no "specific timeline" for rescheduling

Should there be one?

Days ago, Matt Gaetz (R-FL) used his time at a DEA Oversight Committee hearing to pepper DEA Administrator Anne Milgram with questions about the ongoing marijuana rescheduling process. In an effective line of questioning, Gaetz pressed her on the timeline for rescheduling. She couldn’t give one:

As a legal matter, she is plainly right. Although the Controlled Substances Act sets a tight timeline for rescheduling following FDA approval (21 U.S.C. § 811(j)), “marihuana” hasn’t been approved by the FDA. Ergo, no specific timeline.

Moreover, it isn’t even clear, by the letter of the law, whether a formal legal process is underway. Section 811(a) of the CSA states that rescheduling “may be initiated by the Attorney General (1) on his own motion, (2) at the request of the HHS Secretary, or (3) on the petition of any interested party.” As far as I know, the Attorney General hasn’t filed a motion and the HHS Secretary hasn’t requested rescheduling. And who knows what the “letter” from the President to the HHS Secretary and Attorney General says.

We’ve discussed the rescheduling process in detail many times. Check out Shane’s posts here, here, and here. Those explain “the applicable law, the mechanics of the administrative process, and the tedious and enraging history of DEA’s use of that process to keep cannabis in schedule I unlawfully for decades.”

The question I’m going to address for the remainder of this essay is not whether there is a legally mandated timeline. Obviously, there is not. Rather, is a lengthy process legally necessary?

The answer is probably not.

In 1971, DEA’s predecessor, the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD), transferred amphetamine and methamphetamine to Schedule II from Schedule III. Here is what the 1971 letter from the Secretary of HEW (the predecessor to HHS) stated to the Attorney General to support the transfer.

This responds to the request by your department ... that the Department of Health, Education and Welfare consider the scientific and medical facts about the amphetamines and methamphetamines and recommend the proper schedule for these drugs under the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (P.L. 91–513).

I have considered these drugs as provided in Section 201(b) giving specific attention to the factors listed in paragraphs (2), (3), (6), (7) and (8) of subsection (c) of that Section, and the scientific or medical considerations involved in paragraphs (1), (4), and (5) of such subsection. I find that the amphetamines and methamphetamines have a high potential for abuse and are being widely abused; that the drugs have currently accepted medical uses in treatment in the United States; and that abuse of the drugs may lead to severe psychological and physical dependence and has lead to such severe dependence. Accordingly, I recommend that the amphetamines and methamphetamines be placed in Schedule II under the provisions of Section 202 of the above-mentioned law.

Folks, that’s it. Adderall is subject to Schedule II quotas because in 1971, some bureaucrat threw the above two paragraphs on a sheet of paper and mailed it in.

Since then, litigants in criminal cases have repeatedly challenged the sufficiency of this letter. The courts to consider that argument, however—over the years, there have been many—have rejected it. In United States v. Sullivan, 967 F.2d 370 (10th Cir. 1992), for example, the Tenth Circuit stated that “[a]lthough, in retrospect, a more detailed evaluation would have been preferable, we conclude that this evaluation was adequate.” The law today isn’t any different than it was in 1971.

So, if the paragraph above was legally sufficient to move amphetamines and methamphetamines to Schedule II, then the same paragraph reoriented toward marijuana should be legally sufficient to back a Schedule I to Schedule III move, right?

I have considered these marijuana as provided in Section 201(b) giving specific attention to the factors listed in paragraphs (2), (3), (6), (7) and (8) of subsection (c) of that Section, and the scientific or medical considerations involved in paragraphs (1), (4), and (5) of such subsection. I find that marijuana has a potential for abuse less than methamphetamine, cocaine, fentanyl, and heroin; that marijuana has a currently accepted medical uses in treatment in the United States because it is being used medically according to doctor recommendations in a significant portion of the United States; and that marijuana abuse may lead to moderate or low physical dependence or high psychological dependence. Accordingly, I recommend that the marijuana be placed in Schedule III under the provisions of Section 202 of the above-mentioned law.

Could marijuana could be rescheduled in a legally sound manner by a letter hammered out by a middle management bureaucrat remotely while hungover on a laptop in Ibiza? Not quite.

See, for decades now, HHS/DEA have put together hypertrophic evaluations and have come to the conclusion that marijuana cannot be rescheduled. In 2011, DEA spent almost 40-pages on the Federal Register ’splainin’ the no-reschedule decision. Most recently, in 2016, the agencies did a thorough eight-factor analysis to deny a rescheduling petition filed by two state governors. What did they conclude? High potential for abuse, no accepted medical use, and a lack of accepted safety for use. In other words, Schedule I. Why? Although these evaluations say a bunch of stuff, when you distill it down, because marijuana hasn’t been approved by the FDA.

To reschedule marijuana in 2023 or 2024, the government doesn’t need to find more science. The science hasn’t really changed in a legally material way. Rather, they need to change the way they see the evidence that already exists. Don’t believe me? Take the following paragraph stated in the 2016 petition denial to support marijuana having a “high potential for abuse”:

A number of factors indicate marijuana’s high abuse potential, including the large number of individuals regularly using marijuana, marijuana's widespread use, and the vast amount of marijuana available for illicit use. Approximately 18.9 million individuals in the United States (7.3 percent of the U.S. population) used marijuana monthly in 2012. Additionally, approximately 4.3 million individuals met diagnostic criteria for marijuana dependence or abuse in the year prior to the 2012 NSDUH survey. A 2013 survey indicates that by 12th grade, 36.4 percent of students report using marijuana within the past year, and 22.7 percent report using marijuana monthly. In 2011, 455,668 ED visits were marijuana-related, representing 36.4 percent of all illicit drug-related episodes. Primary marijuana use accounted for 18.1 percent of admissions to drug treatment programs in 2011. Additionally, marijuana has dose-dependent reinforcing effects, as demonstrated by data showing that humans prefer relatively higher doses to lower doses. Furthermore, marijuana use can result in psychological dependence.

Has any of this changed? Marijuana in 2023 is even more widely used and therefore, according to the logic above, “abused.” Following the reasoning above, marijuana still has a “high potential for abuse.” Actually, the evidence might be stronger under the reasoning above.

Next consider “currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States”:

FDA has not approved a marketing application for a marijuana drug product for any indication. The opportunity for scientists to conduct clinical research with marijuana exists, and there are active INDs for marijuana; however, marijuana does not have a currently accepted medical use for treatment in the United States, nor does marijuana have an accepted medical use with severe restrictions.

A drug has a “currently accepted medical use” if all of the following five elements have been satisfied:

a. the drug’s chemistry is known and reproducible;

b. there are adequate safety studies;

c. there are adequate and well-controlled studies proving efficacy;

d. the drug is accepted by qualified experts; and

e. the scientific evidence is widely available.

The science here clearly hasn’t changed much. FDA still has not approved a marketing application for a marijuana drug product for any indication. Still, there are no “well-controlled studies proving efficacy.”

Going back to the 2011 evaluation where, to support a “lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision,” DEA identified on page 40585, that “very large epidemiological studies indicate that marijuana use may be a causal factor for the development of psychosis in individuals predisposed to develop psychosis and may exacerbate psychotic symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia.” Did that change? No. Actually, recently in 2023, it was probably confirmed.

I could go on. The bottom line is that there needs to be more than the paragraphs above because as a principle of administrative law, when an agency changes its prior views, that agency needs to explain itself. The explanation doesn’t need to be long, but it can’t be arbitrary or capricious. Rattling off studies and stating the “science has changed” won’t do it here, because really, it hasn’t.

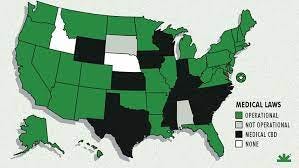

That doesn’t mean a rescheduling evaluation needs to be long, of course. One could, for example, footnote relevant research to support a contention that marijuana isn’t as addictive as fentanyl. One could hyperlink to NORML which lists all the states in which marijuana is being used medically. And if one were really frisky, we could copy-paste a map.

A short 5-page whitepaper citing a few meta-analyses and the facts on the ground that succinctly but clearly explains why the agencies see things differently today should do the trick. And, due to a highly deferential standard of review as to the factual scientific/medical evidence—substantial evidence—it is extraordinarily unlikely that a rescheduling determination in court based on such a white paper could be successfully challenged on grounds that HHS/DEA viewed the research incorrectly.

DEA’s analysis following receipt of the HHS evaluation could be even more brief considering (1) HHS medical/scientific evidence binds DEA and (2) DOJ doesn’t enforce medical marijuana laws at present. In other words, there really shouldn’t be much for DEA to do on this one other than rubber stamping the HHS evaluation. This entire process could be completed in a bullet proof manner in six months.

Here is what I suspect: Data from state medical programs will be more seriously considered toward “accepted medical use.” A couple weeks ago, MJBizDaily reported on Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota and Utah sharing data from their state medical programs. I suspect weight will be put on that data to reach a conclusion that marijuana has an “accepted medical use.” In turn, that will require a new way of thinking about the science/law: that safety/efficacy is not the only way to show “accepted medical use.” And, if that is the reasoning, we’d have a powerful reason to support for data collection initiatives in state-level psilocybin markets.1

So why hasn’t this been done yet, despite President Biden’s directive?

To summarize the above, here’s my answer. Over the years, the rescheduling process—and particularly the eight-factor analysis process—has grown into a giant pile of administrative bureaucratic bullshit in proportion to the growth of FDA and DEA and dominated by pharmaceutical industrial complex type thinking. As the 1971 anecdote illustrates—and as copious legislative history shows—none of this nonsense was contemplated in 1970 when the CSA was enacted. The CSA was supposed to be flexible. Now, we’re fixated—indeed, paralyzed—by “the science.”

But rescheduling marijuana won’t—indeed it can’t—actually be based on new “science” because the science hasn’t materially changed. In 2016, the science said marijuana was less addictive than crack cocaine. Folks, has that changed? Necessarily, rescheduling has to be based on a new way of thinking about the science—and the law. For government bureaucrats, however, thinking outside the box takes time. But it doesn’t have to take more than a year.

For certain drugs or substances, such as new drugs, a more searching scheduling inquiry might be appropriate. But whether marijuana—a drug that has been around forever—ought to be in Schedule I is not one of them. The only relevant data points are whether (1) it has a lower abuse potential than drugs like fentanyl and (2) it is being medically used in treatment in the United States. That’s true both for today and in the past. The answers to these two questions are so obviously “yes” that the process shouldn’t take very long. To quote Rep. Steve Cohen, all of this really is “governmental gibberish.”

And the law clearly accommodates an abbreviated process. But, due to an unhealthy addiction to the FDA approval process, the FDA nanny-state, and is incorrectly seeing the rescheduling process as tantamount to the FDA approval process, the mantra remains “we need to see the data.”2 But again, the data hasn’t shifted in a material way under current legal standards, so the agencies are going to have to change the legal standard.

And here’s the final point: all this is the windup to a proposed rule. As Shane points out, that’s just the first half. The second is a public comment process and/or a formal rulemaking process and hearing where additional evidence can be provided. With Adderall, the agency didn’t receive reams of public comments. Rescheduling has treaty implications and may trigger OIRA clearance. There probably has to be a Regulatory Flexibility Analysis under SBREFA because rescheduling would significantly impact many small businesses. All of these additional variables make it virtually impossible to speculate regarding the timeline with any accuracy.

Long story short, who knows when a rescheduling will happen and become effective. But for the time being, the Administrator is right: there is no timeline.

Note, however, that does not mean that current psilocybin regulatory frameworks are being structured or packaged in a way to produce the data that might be needed to make this showing.

Also, perhaps, rescheduling is being held up as a political/election play. That could backfire, of course, if social justice constituencies come out against rescheduling because it is not descheduling—a position I find to be counterproductive. As I state in Death and Taxes, rescheduling to III is an equity measure of the highest order.

A further clarification on timeline.

What event gets publicly announced first? Does the HHS/FDA determination get announced publicly before the DEA sets the proposed rule? Also, how long does it usually take between the HHS/FDA determination and the DEA proposed rule?

I disagree on the "accepted medical use". The state data will simply show an extremely high safety profile for some state programs, or all of them for all I know. This quote from 1977 is what I base my thinking on.

1977 NORML v. DEA, 559 F.2d 735, 749 (D.C. Cir. 1977)

several substances listed in CSA Schedule II, including poppy straw, have no currently accepted medical use

marihuana could be rescheduled to Schedule II without a currently accepted medical use