(This is a follow-up post to Part 1, which you can read here. Part 1 examines the Schindler Application and concludes that it is nothing more than a recitation of previously known and practiced ideas. Read on for a fuller explanation and integration on the Schindler Application’s filing, including a one-on-one conversation with Carey Turnbull and a couple of quotes.)

Before we attempt to untangle some of these open questions left by Part 1, I want to take a step back and address a legal concept fundamental to both the Ross Application, Schindler Application, and patenting psychedelic medicine generally: Can one take well-known psychedelics and patent a method of treatment? Actually, under the right circumstances, yes.

Let’s start by putting our law hats on.

The Bridge: MOTs

Once again, let’s start with claims.

35 U.S.C. § 101 determines what sorts of discoveries are available for patenting: “Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements” of the Patent Act. In the United States, if a method of treatment is a “new and useful process” of using an old compound, that’s patentable. In some countries, like India, it generally is not or is more complicated.

Method-of-treatment claims or MOTs are typically regarded as second-class citizens in patent world. A MOT does not have the same reach as a compound claim. A compound claim covers not only any use of the compound but also making the compound. In contrast, a MOT involving a compound (say psilocybin) covers only the specific use recited in the claim. All things being equal, a claim to a compound is potentially more valuable—and dangerous: it blocks more behavior.

MOTs are also more difficult to enforce. MOTs involve treatment. Usually it is a clinic, physician, or patient that applies a treatment and therefore infringes a MOT. The problem should be apparent: suing doctors and patients one-by-one isn’t a practical way to enforce a patent.

Fortunately, patent law provides an out in 35 U.S.C. 271(b): “whoever actively induces infringement of a patent shall be liable as an infringer.” That means a patent holder does not have to go after doctors that perform MOTs in a whack-a-mole fashion. It can instead go after a rival company that influences clinics, physicians, or patients to perform the MOT can be sued for patent infringement. But enforcing a patent based on inducement requires not only proving patent infringement, but that the inducer actively encouraged infringement, i.e., knowing that the acts it induced constituted patent infringement. Proving a drug manufacturer is encouraging patients to use a medicine in a certain way can be difficult, especially since doctors ordinarily have wide latitude on treatment regimens.

Also, depending on the claims, a MOT can also be easily practiced around. Infringement only occurs when every step of a patent claim is practiced. If a method requires administering a dose in a certain manner but can be effectively administered in a slightly different manner, the claim can be avoided. I noted that issue at the beginning of the last installment with the NYU Application. The method there required administering psilocybin once. Do it twice and you are in the clear.

On top of all that, compared to compound patents, MOTs do not hold up in court very well. As discussed in the last installment, one cannot patent a newly discovered result of a known or previously practiced process. Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. v. Ben Venue Labs, Inc., 246 F.3d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 2001).

Another case to pay attention to is a case called In re Montgomery, 677 F.3d 1375 (Fed. Cir. 2012). In that case, a prior art reference called HOPE described the design of a large, simple randomized trial involving over 9,000 patients at high risk for cardiovascular events such as stroke, who would receive ramipril and vitamin E to prevent stroke. The study had begun, with all patients having been randomized and receiving ramipril or a placebo for at least one month, but had not been completed.

The Federal Circuit found the claims of the patent anticipated by HOPE. HOPE disclosed a protocol for the administration of ramipril to stroke-prone patients, and administering ramipril to stroke-prone patients inevitably treats or prevents stroke. Montgomery argued that inherent anticipation required that the claimed method have been actually performed. The Federal Circuit concluded that this was not correct: “even if HOPE merely proposed the administration of ramipril for treatment or prevention of stroke (without actually doing so), it would still anticipate.”

Montgomery should be the nail in the coffin to something like a Schindler Application. Not only are the claims anticipated and/or obvious over a bevy of prior art references, but exact protocols were published on clinicaltrials.gov long before the earliest possible priority date.

Those in or investing in psychedelic pharma take note: An enabling disclosure of a clinical trial protocol can anticipate your MOT. File your provisional within a year of publishing a protocol. This is important since a fairly recent 2017 Final Rule under Section 801 of the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 requires the public disclosure of information such as study protocols or the “the written description of the clinical trial, including objective(s), design, and methods” — information that could anticipate a broad MOT.

Returning to the Schindler Application, its fundamental problem isn’t that it seeks to patent a MOT. Under US patent law, that’s fine. Rather, the issue is that one can’t mine the internet and communities for old ideas, conduct a survey, do clinical research to verify the results of the survey, and then claim one discovered or invented what had been previously known, practiced, and published. And if you want MOTs, file your provisional shortly after submitting for your clinical trials. Don’t wait years or you may find yourself behind the 8-ball like the Schindler Application and anticipating yourself.

So why go to the MOT?

Despite the inferiority of MOTs, pharma companies sometimes file for them. And as we’ve seen, apparently psychedelic pharma companies do too. Why this is so is straightforward: If a compound is well-known and you want to get proprietary rights on research, sometimes all you can (validly) get is a MOT.

Under the right circumstances, a valid MOT can be lucrative. For example, Merck had long marketed finasteride, an anti-androgen, under the trade name PROSCAR, to treat enlarged prostates. Finasteride was patented in 1984 and approved for medical use in 1992. Merck then discovered that the anti-androgen compound also treated male pattern baldness. And so, Merck’s cash-cow Propecia was born under the aegis of US Patent No. 5,547,957. (Serious depression and suicide risks be damned!)

Eli Lilly’s ADHD drug Strattera is another successfully repackaged drug. The broad claim protecting Strattera was a “method of treating ADHD comprising administering to a patient in need of such treatment an effective amount of tomoxetine.” At the time Lilly filed for the MOT, tomoxetine was a known compound, described and claimed in Lilly’s own U.S. Patent No. 4,314,081, issued February 2, 1982. More than ten years later, Lilly scientists suggested using tomoxetine to treat ADHD. Many were skeptical, but Lilly did tests in 1994 and submitted an Investigational New Drug Application in January 1995 along with a patent application directed to a MOT. Clinical trials ensued. And after seven years of successful experiments, the compound proved effective and FDA approved the use of tomoxetine for treatment of ADHD. Lilly then made bank in the lucrative market for ADHD meds.

Several companies sued Lilly to try to invalidate the patent and bring a generic to market. They lost. Experts for both sides agreed at the trial that they would not have expected that atomoxetine would be a successful treatment of ADHD. Importantly, the court also concluded that the patent was sufficiently enabled even though human test data were not available at the time the patent application was filed. That means if you are a psychedelic pharma company trying to patent a MOT corresponding to a method used in clinical trials, you may not need to show clinical effectiveness of the MOT prior to filing that patent application.

The reason for obtaining MOTs in psychedelic medicine is even more apparent. Many psychedelics have been known for decades and are off-patent. The classics are known. Many exist in nature. Between PiKHAL and TiKHAL you can find another 200 or so synthetics. These compounds and many others have been sitting out in the open and for decades. But due to draconian regulatory restrictions, they have been impossible to rigorously study. We are only getting around to that. If you are looking for IP to protect your investment and you are studying a classical psychedelic, a MOT may be all that is available.

MOT + Regulatory Environment = $$$?

Valid MOTs might carry additional value in the age of psychedelic therapy and controlled substances space due to the peculiar and restrictive regulatory environment in which they operate.

Start with rescheduling. In the past, when DEA reschedules a substance, it reschedules only the FDA approved formulation of that substance. For example, when it rescheduled the synthetic THC product Syndros, it rescheduled FDA approved products containing dronabinol—and left synthetic THC behind. Does this make sense? Probably not. Is rescheduling an FDA approved product and not the underlying molecule open to a legal challenge? You bet. But unless you want to challenge DEA in court—and in my experience, few do—this is your future. When COMP360 or any other psilocybin drug is approved by the FDA, DEA will reschedule FDA approved products containing synthetic psilocybin. Psilocybin will remain Schedule 1.

And then there is FDA. Beyond default regulations that apply to pharmaceuticals (such as labeling requirements) there are REMS or “Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies.” REMS is a drug safety program carried out by the FDA where the agency can require for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks. REMS requirements can include forcing a drug manufacturer to develop materials for patients, such as medication guides or handouts for patients distributed with many prescription medicines.

Per the FDA guidance, “[i]f FDA determines that a REMS is necessary, the Agency may require one or more REMS elements, which could include a Medication Guide, a patient package insert, and/or a communication plan. For example, “[t]hese handouts contain FDA-approved information in patient-friendly language that can help inform patients about how to use a medication and avoid serious adverse events.” Similarly, a REMS can require the drug manufacturer to communicate directly to health care providers, pharmacists, nurses and other participants involved in the delivery of health care or medications.

Spravato, for example, the FDA approved formulation of intranasal esketamine, is only available through the Spravato REMS. The REMS even has its own website. It requires inpatient screening, outpatient screening, certified pharmacies, and patient enrollment. It is widely acknowledged that that some psychedelic drug (or at least the current generation) has potential for abuse, and is expected that if they get approved, they will be subject to a REMS.

One of the weaknesses in MOTs is off-label prescribing and the practicalities of enforcement at the clinic/doctor level. Another is that a MOT can be practiced around. But suppose a REMS required a manufacturer (branded or generic) to adhere to a specific dosing regimen or distribute pamphlets or handouts that specifically instruct a physician or patient to administer a treatment in a certain way according to the MOT. Or maybe the REMS requires registration and screening, as is the case with Spravato. Suddenly, that MOT got a whole lot stronger because of inducement liability discussed above. Depending on the REMS, it might be difficult if not impossible to comply with the REMS and avoid the MOT.

So if you are a cold-blooded capitalistic psychedelic pharma company with a MOT patent, you may actually want REMS from the FDA because it could force folks to fall into your MOT. Strict regulations can actually enhance the value of a patent monopoly.

In conclusion, the MOT value grows because of a regulatory thicket that surrounds the pharmaceutical process and works in tandem with the patenting process. As we progress, keep your third-eye peering at the regulatory process. That’s where the action is, and why some patents that might ordinarily be worthless—say on a particular GMP crystalline form of psilocybin— may actually carry tremendous value if valid.

Part 2: Integration

In the last installment, I offered the following take:

[T]he NYU Ross crew did one study in 2016 and repeatedly published follow-up studies. Now, years later, they are trying to put the toothpaste back in the tube and seeking to monetize the research by obtaining patent protection for a study that is already thoroughly disclosed in the prior art. Our patent laws say this is a no-go.

My take here with the Schindler Application isn’t much different. The Yale crew did a survey in 2015. Now, years later, they are trying to put the toothpaste back in the tube and seeking to monetize the research by obtaining patent protection for information that is thoroughly disclosed in the prior art.

But to get a better understanding of what is happening here, we need to take another step back. These filings are not happening in isolation. They are happening in a rapidly growing psychedelic patent ecosystem. Here, we’re going to look at the players, factions, and origins involved in the Psychedelic Patent Wars™ (or at least on the psilocybin front).

Let’s start with early psilocybin research and our old friend 2016 Ross.

The Promise of Psilocybin

As seen above, psilocybin has been used medically, albeit illegally, to treat cluster headaches for decades on the basis of anecdotes and self-experimentation. But until very recently, clinical evidence supporting such use remained thin.

In the early 2000s, research almost exclusively funded by philanthropy and grants began to explore psilocybin’s potential in treating mental illness, for example:

The 2006 Moreno psilocybin/OCD study conducted from 2001 to 2004 and supported by MAPS and the Heffter Institute showed safety in 9 patients and a reduction in OCD symptoms.

The 2006 Griffiths double-blind study found that when administered under supportive conditions, psilocybin occasioned experiences similar to spontaneously occurring mystical experiences. This study was supported by a government grant and the Heffter Institute. [Correction: per the link, the study was supported by NIDA and the Council on Spiritual Practices]

The 2011 Grob study examined 12 patients and showed safety in advanced cancer patients and reduction in anxiety symptoms. This study was also supported by philanthropy, as well as a government grant.

These early pilot studies, largely supported by grants and philanthropy, did not study many people. All showed promise but none laid solid groundwork for Phase II clinical trials needed to get a psilocybin-based drug through the FDA.

The 2016 Ross study wasn’t the first to study psilocybin in a clinical setting. But it did examine 29 people and along with the 2016 Griffiths study, provided excellent experimental data from which additional, more advanced clinical trials could launch:

The 2016 Ross study, like predecessor psilocybin studies, obtained financial support from a number of philanthropic outlets, including RiverStyx Foundation, the Heffter Research Institute, and a number of individuals.

The 2016 Griffiths study reports funding from a similar crew:

Next, I want to focus on two sets of groups here who have come to represent different factions in the Psychedelic Patent Wars.™

COMPASS Charts a Course…To the Patent Office

Husband and wife George Goldsmith and Ekaterina Malievskaia established COMPASS in 2015 as US/UK non-profit. According to Malievskaia, in 2014, they were so impressed with researchers at non-profits MAPS and Heffter that they not only offered financial support to the field, but helped with regulatory strategy so that patients could benefit sooner. They then formed a non-profit called COMPASS to support research into psilocybin for hospice patients on the Isle of Man and 100% funded the operation themselves. In August 2016, Heffter researchers asked COMPASS to write regulatory commentary on the upcoming publication of two landmark studies of psilocybin for cancer-related distress. Non-profit COMPASS shared the details of these discussions with both Heffter and Usona to help inform their regulatory strategy and further study designs.

Moving forward, COMPASS ran into a problem: Although there were no political impediments to developing psilocybin into medicine, the clinical research path required navigating through pharma issues, such as the cost of obtaining GMP psilocybin due to regulations. Also, certain tax credits were not available for non-profits. Malievskaia explains the fundamental problem the company faced:

As the previously published synthesis processes did not scale to meet regulatory standards, we had to invent our own process. As he would have done for anyone who would have asked for his help, David Nichols advised our manufacturing team. With his support our team has solved over 60 distinct technical problems in the synthesis and formulation process. Some of these inventions became the basis for our manufacturing patents. In general, patents provide an opportunity for an organization willing not only to take a significant financial risk to recoup the expenses, but more importantly, to ensure integrity of the data collected before and after the approval.

From the fires of this regulatory quagmire, the for-profit life sciences company COMPASS Pathways was forged. Goldsmith and Malievskaia had been getting nowhere. Then they met Christian Angermayer, who with other investors, capitalized the enterprise and took it in a solid for-profit direction. And with that turn, COMPASS could, among other things, fund a GMP-compliant, scalable and reproducible manufacturing process.

More recently, COMPASS CEO Goldsmith explained, “Patents enable us to continue to do the highest quality clinical research so we can work to bring therapies to patients who are suffering with serious mental health challenges and have few options.” According to COMPASS, these patents promise investors a higher future return on investment, the company can more effectively raise capital to complete an expensive clinical trial process. Angermayer, in an open letter responding to a Tim Ferriss blog post, explained the COMPASS approach:

As you are likely well aware, the cost to bring a drug to market is often measured in hundreds of millions of dollars and approx. 7-10 years of development time, depending upon the stage of initial development. As such, timely access to large amounts of capital is critical. Given those timelines and amounts needed, it should come as no surprise that investors want to eventually see a substantial return on their initial investment. An alternative way to think about this: the not-for-profit, donation driven model has been a challenge, given the sheer sums of money required for commercial drug development on a yearly basis.

Given the complexity of commercialization due to the inclusion of therapy (the paradigm shift noted above is a double-edged sword), the ramp up of sales might in some cases be slower than a new drug that is prescribed in the traditional way. This, in turn, means that maintaining exclusivity—through both intellectual property and regulatory strategies—is even more necessary so as to ensure the return on investment required by investors.

Without the chance of turning millions into billions, the investors disappear, and without the hundreds of millions of dollars from investors, progress to bring these medicines to patients slows to a glacial pace. Patent & data exclusivity help set up an incentive structure to make something happen that otherwise would not be happening – building a new therapy, even from a psychedelic, is not a zero-sum game.

Not surprisingly, shortly after obtaining its first patents on COMP360, COMPASS made a beeline to the NASDAQ to raise $100 million in public capital. All the while, its clinical trials have been moving forward swiftly. Its Phase 2 trials reported positive results and, using the capital it has raised, the company is moving forward into more trials for an array of indications.

No Patents, No Problem! (Yet)

While COMPASS, according to its for-profit philosophy, went about making its synthetic form of psilocybin proprietary, other supporters of psilocybin-as-medicine chose a different path.

Most prominent is Usona. Inspired by the academic research with psilocybin and those having existential distress from cancer—and several years before COMPASS began pounding the Patent Office—Bill Linton and Malynn Utzinger formed the Usona Institute in Summer 2014. Usona is a 501(c)(3) non-profit medical research organization dedicated to supporting and conducting pre-clinical and clinical research to further the understanding of the therapeutic effects of psilocybin and other consciousness-expanding medicines.

The two approached researchers at Johns Hopkins and UCLA to ask them what they needed to move the research forward. And what they realized is that they needed to create an organization to carry psilocybin through the FDA clinical trial process. Like COMPASS, Usona manufactures its own pharmaceutical-grade psilocybin, is in the process of complete Phase 2 clinical trials, and is mobilizing for Phase 3 trials.

Carey Turnbull, a board member at Usona and President of the Heffter Institute, founded his companies in a similar vein. For example, as discussed above, he started B.More, a 501(c)(3) non-profit company to study psilocybin, a classic psychedelic, to treat patients suffering from Alcohol Use Disorder. B.More has been successful at moving psilocybin through the FDA process thanks to collaborations with leading institutions and stakeholders in psychedelic research and the treatment of addiction, including NYU School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Usona Institute, and the Heffter Research Institute.

Relevant here, in contrast to COMPASS, Usona, Turnbull, and others have taken a different position on patents: open science built on research sharing approaches that were the norm and practiced all the way up to 2016. Usona has not patented the formulation of synthetic psilocybin it uses. Even more, it makes it available free of charge as an investigational drug to other qualified researchers studying a variety of conditions, such as substance misuse disorders or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Open-source psilocybin. As mentioned above, Turnbull has taken a similar approach with LSD.

A Conversation With Carey

Because of his public positions and important contributions, I reached out to Turnbull directly to figure out what was going on with the Schindler Application, which has since been assigned to Yale and the VA and is being prosecuted by them. Turnbull graciously gave me some time to explain some of his thinking.

We had a long discussion that spanned the Turnbull’s work, my own work, and meaningful ways to improve the patent system. Turnbull explained how he had philanthropically supported numerous studies on psilocybin use, including the 2016 Ross study, to the tune of around $20 million of his own money. He pointed out that COMPASS, like everyone else, stands on the shoulders of this early philanthropically funded academic work that everyone is relying on. He also identified difficulties in raising money to conduct Phase 3 trials. He underscored the race to get the first psilocybin product through the FDA clinical trial process and the need to enable equitable access to high-quality, low-cost psychedelic medicine.

Setting aside the assignment back to Yale, I asked Turnbull if the Schindler Application had been filed defensively. Per Techopedia a defensive patent is:

[A] patent that is used with the primary intention of defending a company against patent infringement lawsuits. This differs from more aggressive uses for patents, which can include generating royalties or preventing competition through legal action. A defensive patent can protect a patent holder by allowing it to countersue after a competitor sues for infringement - or even if the competitor sues for some other reason. A large collections of patents can also protect a company by deterring lawsuits altogether.

Think of a defensive patent as a shield to patent-holding competitors. Better yet, a shield with a pointy thing in the middle that pokes back to cause harm only when its holder is attacked:

Another reason to pursue a patent defensively is that it prevents another company from obtaining or enforcing a patent on the same subject matter. It is a common misconception that having a patent entitles one to use the patent. Actually, a patent is a right to exclude others from practicing the patent, not an affirmative right to practice the patent. If the only way A can practice a patent is to infringe B’s patent, then B is said to have a blocking patent: an patent that prevents practice of a later invention. Having blocking patents are useful to have defensively. And filing for a patent can ensure a competitor cannot get a later patent on the same or substantially the same thing.

In e-mail correspondence following our discussion, I asked Turnbull whether, similar to his letter to COMPASS, he would neutralize the patent by signing something like a defensive patent pledge. Turnbull explained that he signed the Open Science document, a pledge made by scientists, scholars, practitioners, and organizations to commit to certain principles, and repeated this to me in a follow up e-mail. Relevant here, the Open Science document contains the following principle:

4. Non-interference. We will strive to place our discoveries into the public domain, for the benefit of all. If we have patents or patents pending, we will license that intellectual property, for no more than reasonable and ordinary administrative costs, to anyone who will use it for the common good and in alignment with these principles.

The Open Science pledge is a laudable document. But as the lawyer in the room, let break some bad news to everyone: it is toothless and carries no legal force or effect. A promise to place “discoveries into the public domain” and license intellectual property “for no more than reasonable and ordinary administrative costs, to anyone who will use it for the common good and in alignment with these principles” — which is internally inconsistent — binds signatories in the same way promising to be monogamous prevents cheating: it doesn’t. Also, nothing binds any of the signatories from filing for a patent and assigning or licensing away patent rights to a cold-blooded company that has no intention of complying with the pledge.

For this reason, in the last installment, I floated the idea of the industry actively working to create a defensive patent license to legally protect an open science approach. Such a license could encumber a patent and ensure its use defensively.

This is not a new idea. What may be happening in the psychedelic space—for-profit companies piggybacking off early open science to create more sophisticated, not-to-be-shared proprietary products and processes—shares some similarities with how the software industry evolved. In the earliest days of computing, academics and researchers openly shared source-code to allow bug-fixes. Openness and cooperation reigned. As companies entered the fray and as computing grew larger and more sophisticated, the free sharing of source code stopped. Companies began routinely charging for software licenses and imposed legal restrictions through copyrights. Bill Gates famously wrote an essay entitled "Open Letter to Hobbyists," asking hobby programmers to pay up.

Despite the dominance of proprietary software, free and open-source software survived and prospered in part to an innovation by free software advocate Richard Stallman and the Free Software Foundation: copyleft. The concept, incorporated into the General Public License, used copyright defensively to facilitate sharing. Anyone could use or modify a work for free under the license, but derivatives had to remain available under the same terms, thus preventing downstream authors or users from taking the initial freely shared work and making proprietary software. The license facilitated contribution to a robust commons. Linux, for example, is copylefted and runs most of the internet. Wordpress—started by psychedelic research supporter Matt Mullenweg—is also copylefted and powers around a third of the internet. Turns out, you can make a lot of money sharing.

One could see how a patent-left license could protect the appropriation of “open source” tools into a for-profit patent protected vehicle. For example, one could condition funding, participation, or co-operation on a legally enforceable pledge to only use any patents obtained defensively or require licensing inventions connected to the freely provided tools on fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory terms.

As of today, such a patent license for the psychedelics industry does not exist. In a follow-up e-mail to Turnbull, I proposed the Defensive Patent License in the interim. After my outreach, a Ceruvia spokesperson offered me the following statement:

We are committed to operating our business to the highest standards of integrity, transparency and accountability to enable equitable access to high-quality, low-cost psychedelic medicines. This includes ensuring that the claims in any patents we license can be defended under the requirements of U.S. patent law. As such, we are working with Yale to identify any potential deficiencies in the patent application.

In addition, Turnbull stated he is “always open to exploring any idea that will further my goal of ensuring wide-spread access to psychedelic medicines for patients in need.”

For the record, I believe them. Their is a track record here and it supports them. And I have little reason to question that whatever they are doing on the patent front is to ensure equitable access to medicines to patients in need. But I call them like I see them. And in this one case, due to the many deficiencies identified above—some of which cannot be fixed—it is my opinion that this application cannot be saved.

The Patent Prisoner’s Dilemma™

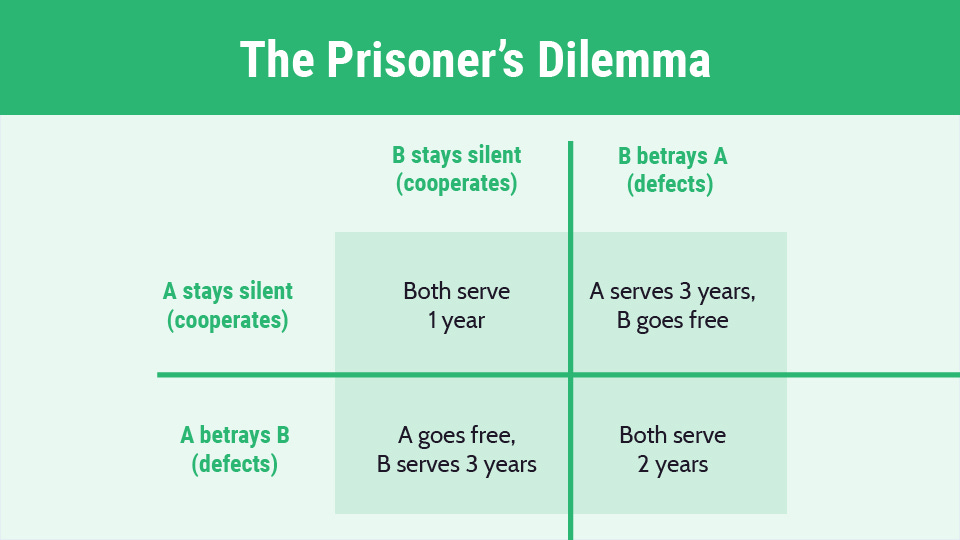

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a game theory concept where parties have an incentive to act in a way that creates a less than optimal outcome for the individuals as a group and/or society as a whole. In the classic form of the game, if A and B betray each other, they both serve two years in prison. If one betrays the other and the other remains silent, the betrayer is set free and the betrayed serves three years in prison. If neither betrays the other, both serve a year in prison.

This concept may describe the emerging Psychedelic Patent Wars™. The optimal approach for society and the group is co-operation (top left). But for A individually, the optimal profit maximizing approach is to file for patents to gain exclusionary rights (bottom left). And with patents, A can raise capital more easily on public and private markets and race ahead of competitors. With a good enough patent, it can exclude competitors.

Now say you are B and compete with A. You know A has turned to the dark side and filed for patents. Maybe its patents cover what you do or come close. Your choices are now: don’t file for patents and potentially lose more while the competitor grabs funding and races ahead; or defect, get your own patents, and both you and A lose, but you lose less. Perhaps you have no intention of asserting the patents. But unless you have patents, you cannot play the game. By getting the patents, you can at least hold them defensively in case A asserts the patents against you or use them as bargaining chips in a cross-licensing deal.

Again, the optimal strategy is for society is the top left. But we end up at the bottom right where the only winners are patent lawyers and litigators. Like me.

This dynamic is not new. A decade ago in the Smartphone Wars, once Samsung entered the smartphone market with Android and started to gain market power, Apple asserted its patents against Samsung and played a “chicken game of patent litigation”:

The dispute spawned 50 lawsuits in 10 different countries over seven years, In the end, neither had much to show for it. After settlement, Apple “walked away with negligible profits on the cases” and presumably a cross-license.

Taking bad patents of competitors down one-by-one is an alternative. But like enforcing patents whack-a-mole style, it becomes prohibitively expensive, especially because it is usually cheaper to spawn patents then get them discarded. Sometimes, the better strategy is to have your own patents as a deterrent, or more important, to use as fodder in cross-licensing to avoid litigation and enforcement altogether. Hence, why companies that typically do not assert patent rights in court, like Google, obtain patents and use patents to cross-license.

Importantly, this Patent Prisoner’s Dilemma™ dynamic kicks in as early as the money raising phase for clinical trials. Bringing medicine through the clinical trial process according to FDA regulations is expensive, often prohibitively so. The money to fund these trials has to come from somewhere. Sure, it can come from philanthropy. But unless an Elon Musk type peels off .1% of his net worth for nothing in return, philanthropy can only get you so far. Hence, the need to raise private and public capital. Or you can turn to a venture debt-type deal like MAPS. Put simply, if companies file for patents and promise better returns based on the promise of exclusionary or defensive IP rights, even if those rights may never materialize, in an efficient market, sources of capital will gravitate to the company seeking IP rights.

To be clear, bad patents are bad patents no matter who files for them.1 But it is important to understand the market behavior here and why this happens. This isn’t necessarily (pure) greed. In some circumstances, filing for bad patents can be a rational reaction and a natural consequence of a complicated dynamic in an emerging space.

Return to the Smartphone Wars. In 2005, Creative obtained a patent that covered a “System for Selecting and Playing Songs in a Playback Device with a Limited User Interface” corresponding to its portable music player, the Zen. Then it sued Apple over the iPod. Three months after getting sued, Apple settled. Then, Steve Jobs declared: “we’re going to patent it all.”

From that point on, Apple bombarded the Patent Office with a mix of genuine innovations and bogus filings—filing for patent applications even when they knew the idea couldn’t be patented. “That’s a patent,” the lawyer said at an invention disclosure meeting. “There’s another one.” According to Apple’s General Counsel in 2006, the “attitude was that if someone at Apple can dream it up, then we should apply for a patent, because even if we never build it, it's a defensive tool.” If nothing else, the patent-everything strategy “prevents another company from trying to patent the idea.”

Whatever one thinks of Steve Jobs, he wasn’t dumb. In this game of self-preservation (or mutual destruction), even a company with no intention of excluding competition might need patents or some other proprietary rights to defend, fight back, or prevent it from getting excluded. Even if you’d rather promote cooperation and sharing, you may need a copyleft or patent-left defense. Otherwise, you “stay silent” and could get stuck in prison while your competitors go scot free.

All this is to say that the “psychedelic patent problem” and patent system are complicated. And maybe the root issue is not, in fact, just the patent system.

Conclusion

Folks, I’m lost. Maybe you are too.

Busting bogus psychedelic patent application filings is fun. But busting patents one-by-one is not a lasting solution. And calls to abolish the patent system for psychedelic innovations entirely is not productive either.2

There is more to untangle to fully understand the deeper-seated issue. The next installment will approach from a different angle to penetrate deeper into this heart of darkness and, hopefully, shed more light.

Until next time.

Good patents are also good patents. I’ve got nothing against patents covering extraction technologies, delivery mechanisms, new molecules, and truly novel methods of treatments. Innovating costs money and these innovations further the art. And I do not believe that innovations relating to psychedelics (pharmaceutical or otherwise) should somehow be treated differently than innovation in any other space.

Among other things, if one wants to prohibit patents relating to “psychedelics,” how does one define “psychedelic” in a coherent way? The essay itself illustrates the problem. It calls ketamine a “a psychedelic anesthetic” even though many scientists and academics—perhaps most—do not regard ketamine, an NMDA antagonist, a “psychedelic.” Whether ketamine is a psychedelic is subject to significant debate illustrates the problem in creating special rules for “psychedelics,” because it is not clear what medicines would fall into the psychedelic bucket.