The first installment covered a lot of ground. After starting with some patent law basics, we stripped down the NYU/Reset Pharma application that seeks to patent a method of treating cancer patients with anxiety by administering psilocybin once.

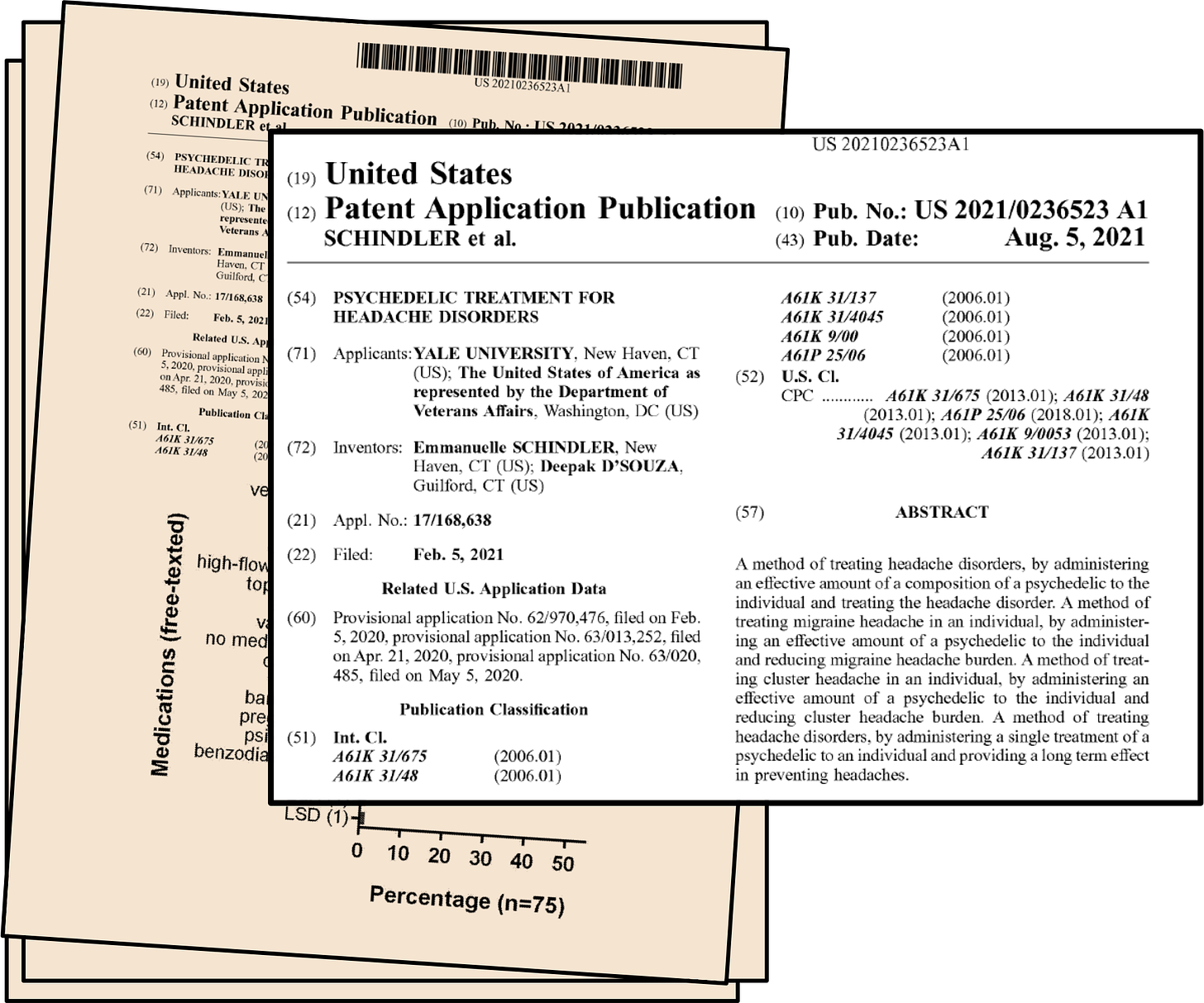

We ain’t even got our feet wet yet. This second installment will examine a new pile of Hot Psilocybin Patent Garbage™ entitled “Psychedelic treatment for headache disorders” or the Schindler Application. It proceeds in three sections:

Part 1 will undress the Schindler Application.

The Bridge will introduce a little more patent law to explain these method-of-treatment patents both generally and in psychedelic medicine.

Part 2 is integration.

Take a breath and make it big.

The Schindler Application

The Claims

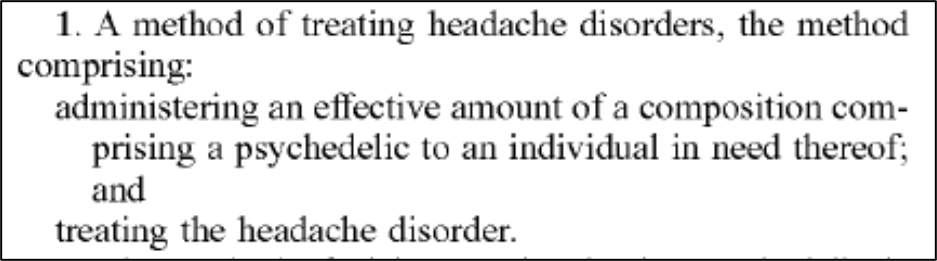

Claim 1 of the application is shown below:

What does “effective amount” mean? According to the specification, an amount “effective to achieve improvement including but not limited to improved survival rate or more rapid recovery, or improvement or elimination of symptoms and other indicators as are selected as appropriate measures by those skilled in the art.” In other words, an amount that results in improvement. Like “alleviate” from the last installment. In emoji, Claim 1 approximates the following:

Recall the claim, not the specification, defines the scope of protection. To infringe a patent, all elements of at least one claim must be present in a product or performed by an entity. If even one element is missing, there is no infringement.1 In the case of Claim 1 in the current Schindler Application, if you give an individual with a headache disorder a psychedelic to treat the headache and achieve any improvement, you infringe.

This same “all elements” test also applies to anticipation or showing a claim is invalid because it is not new. If every element of a claim is found in a prior art disclosure, the prior art anticipates. Thus, in patent speak, we say: “That which infringes if later, anticipates if earlier.” In the case of Claim 1, any prior art reference that shows effectively treating a headache disorder with a psychedelic will anticipate.

Claim 1 is what is called an independent claim or a standalone claim because it contains all the limitations necessary to define an invention. Patents usually also have dependent claims. Dependents claims incorporate by reference all the limitations of the claim to which it refers and then adds another element or limitation. Thus, dependent claims, which add to the independent claims, are narrower because they add more limitations to what is claimed.

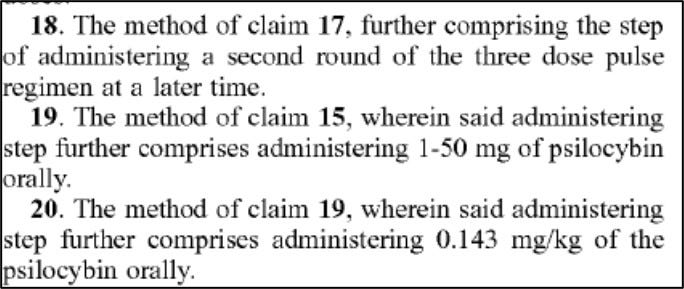

Below, we see some dependent claims of the Schindler Application. These claims add additional elements to a basic independent claim (not shown) that is essentially the same as claim 1—treating a headache with a psychedelic.

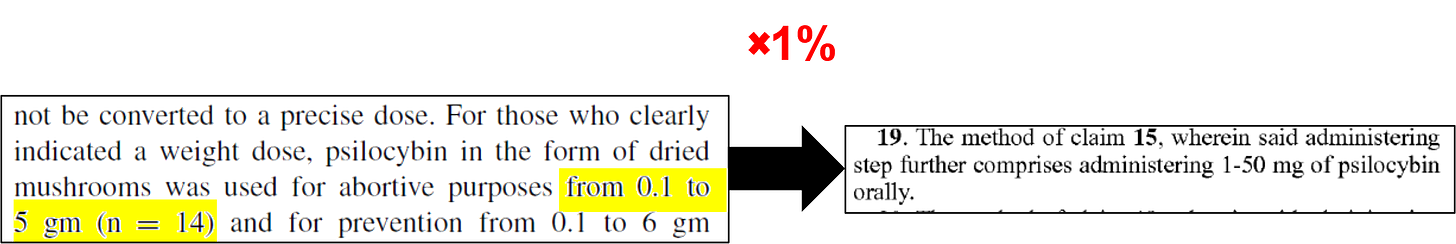

In sum, the Schindler Application seeks claims on a method of treating headaches by administering a psychedelic. In the independent claim, the dose needs to be “effective.” The dependent claims add further limitations to the dosing regimen. In a dependent claim like claim 19, the dose can be anywhere from 1 to 50 mg of psilocybin—from micro- to heroic dose. In further dependent claims, such as claim 20, a specific dose is claimed.

So far, so good.

Priority

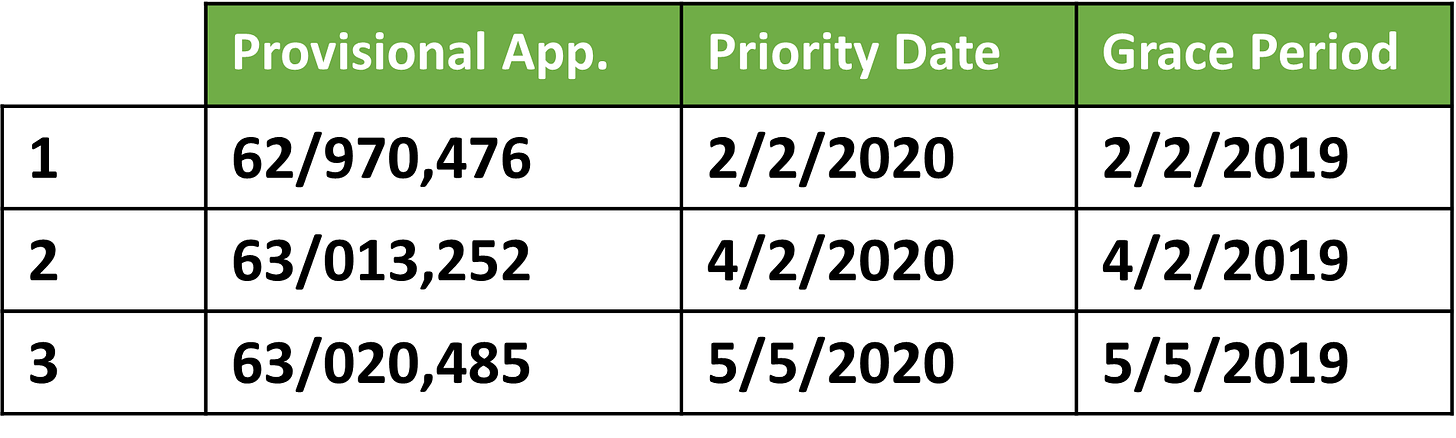

Nailing down the priority date for the claims is critical to patent busting. Recall from the last installment that the priority date dictates what qualifies as prior art. In general, matter disclosed before a priority date is prior art; matter disclosed after is not. There is also a limited exception for disclosures by inventors. The law gives inventors a one-year grace period, so inventors have up to one year from their earliest date of public disclosure of their invention to file a US patent application.

The Schindler Application lists a trio of potential priority dates corresponding to three different provisional filings:

As explained last time, a provisional patent application serves as placeholder for a non-provisional application that allows an inventor to get an earlier priority date. The reason for this is a statute, 35 U.S.C. § 119(e):

An application for patent filed under section 111(a) or section 363 for an invention disclosed in the manner provided by section 112(a) (other than the requirement to disclose the best mode) in a provisional application filed under section 111(b), by an inventor or inventors named in the provisional application, shall have the same effect, as to such invention, as though filed on the date of the provisional application filed under section 111(b), if the application for patent filed under section 111(a) or section 363 is filed not later than 12 months after the date on which the provisional application was filed and if it contains or is amended to contain a specific reference to the provisional application.

What this means is:

But as the statute quoted above shows, this is just a priority claim. For that claim to be legally effective, the provisional must disclose the invention “in the manner provided by section 112(a).” That means an effective provisional can be rough, but must provide adequate support for the claims to show that the inventors actually invented and enabled the claims on the filing date of the provisional.

With a troika of provisionals backing the Schindler Application, to determine the priority date, we have to look at each provisional to see what each discloses. Before we make that detour, however, let’s keep running through the written description or specification of the Schindler Application to see all that appears before the claims.

The Written Description

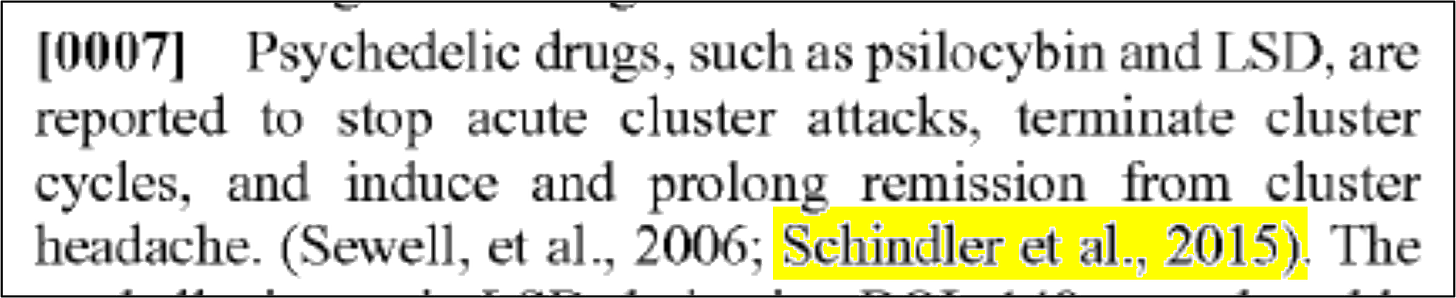

The beginning of the Schindler Application discusses what the inventors did not invent. Paragraph 7, for example, cites two prior art papers that report use of psychedelic drugs to stop cluster headaches. One of those two papers is 2015 Schindler. Pay attention to that one. It will be important.

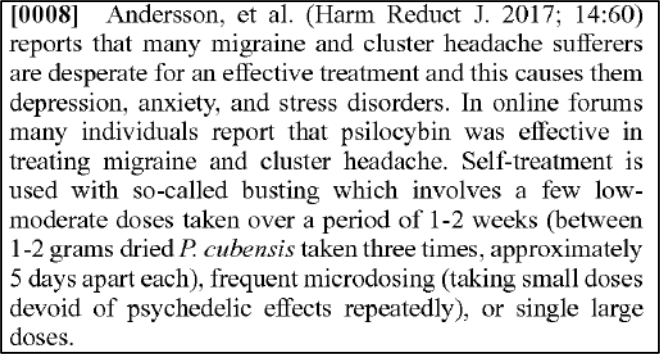

Paragraph 8 goes on to talk about how individuals in online forums report using “low-moderate doses” taken over “1-2 weeks,” “microdosing,” or “single large doses.”

Section 102 says, “a person shall be entitled to a patent unless … the claimed invention was patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.” It does not say “a person shall be entitled to a patent if … the claimed invention was patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.” And yet, the opening lines of the Schindler Application admit most of the claims were not only broadly practiced in the prior art at various different dosing regimens, but documented in several research papers.

But summarizing the prior art like this is not uncommon. Sometimes a specification has a section called “Discussion of Prior Art” or the like. But since you cannot patent the prior art, patents often go on to explain what is missing from the prior art, how the prior art is being improved upon, or why the invention is different. The Schindler Application has relatively little to say in this regard:

As one pages through the specification, the nature of this beast comes to the fore. There is filler, such as the beginning paragraphs that explain what “headache disorders” and “psychedelics” are. There is leave no-stone-unturned-rhetoric, such as a reminder that compounds can be administered “orally, rectally, sublingually, subcutaneously, or parenterally, including intravenous, intraarterial, intramuscular, intraperitoneally, intratonsillar, and intranasal administration as well as intrathecal and infusion techniques.” And then there is my favorite sentence: “The patient being treated is a warm-blooded animal and, in particular, mammals including man.”2 Good to know.

Sprinkled in the specification are a few glimmers of plausible originality. In paragraph 30, for example, we see a reference to clinical trial NCT03341689 and a dosing regimen:

The meat of the specification is the three examples at the end—Examples 1, 2, and 3—which the patent calls “experimental examples.” Only Examples 2 and 3 are “experimental,” however.

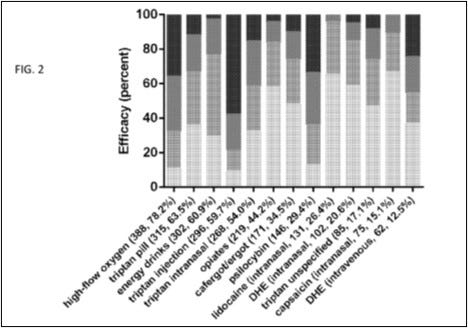

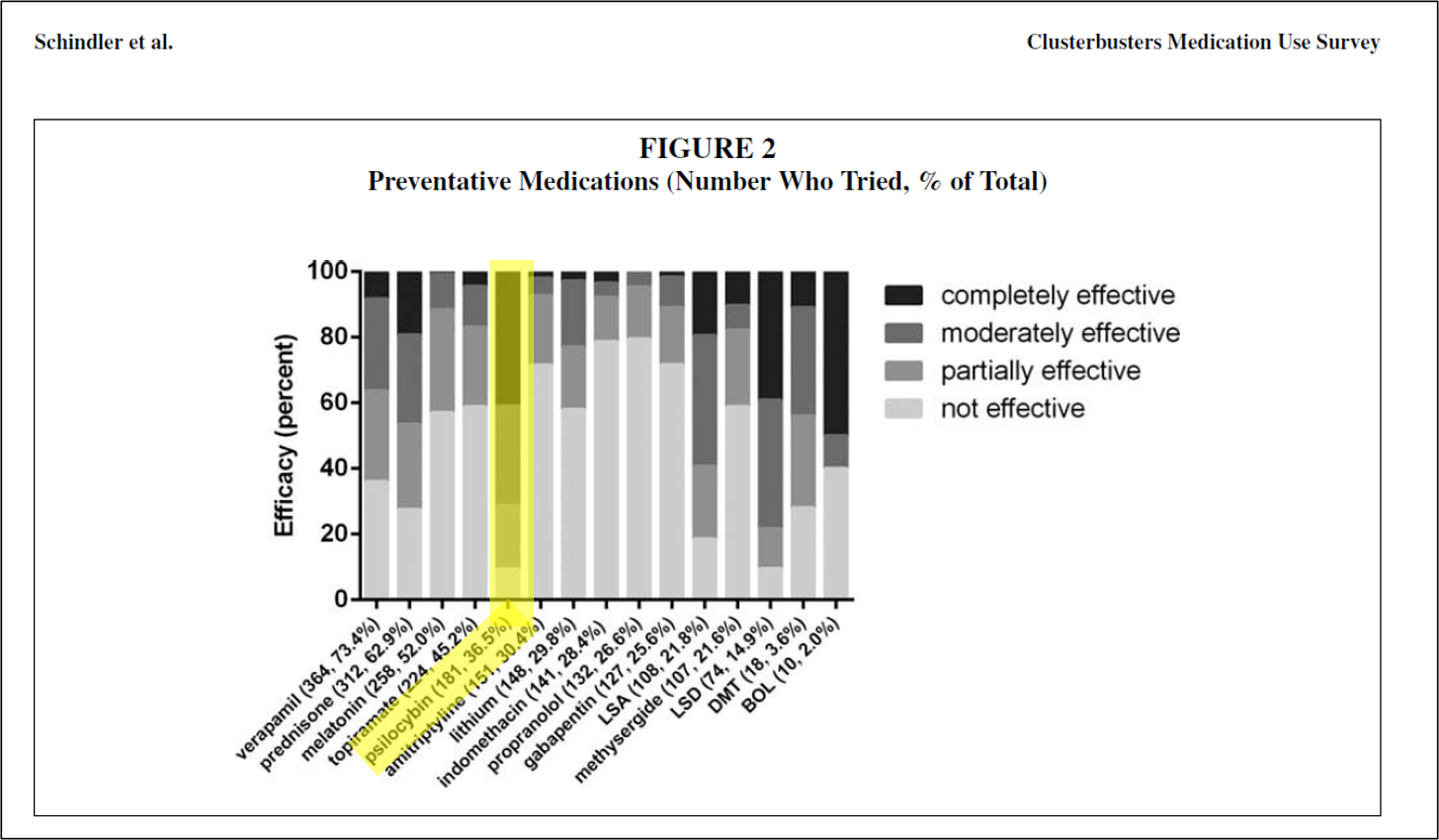

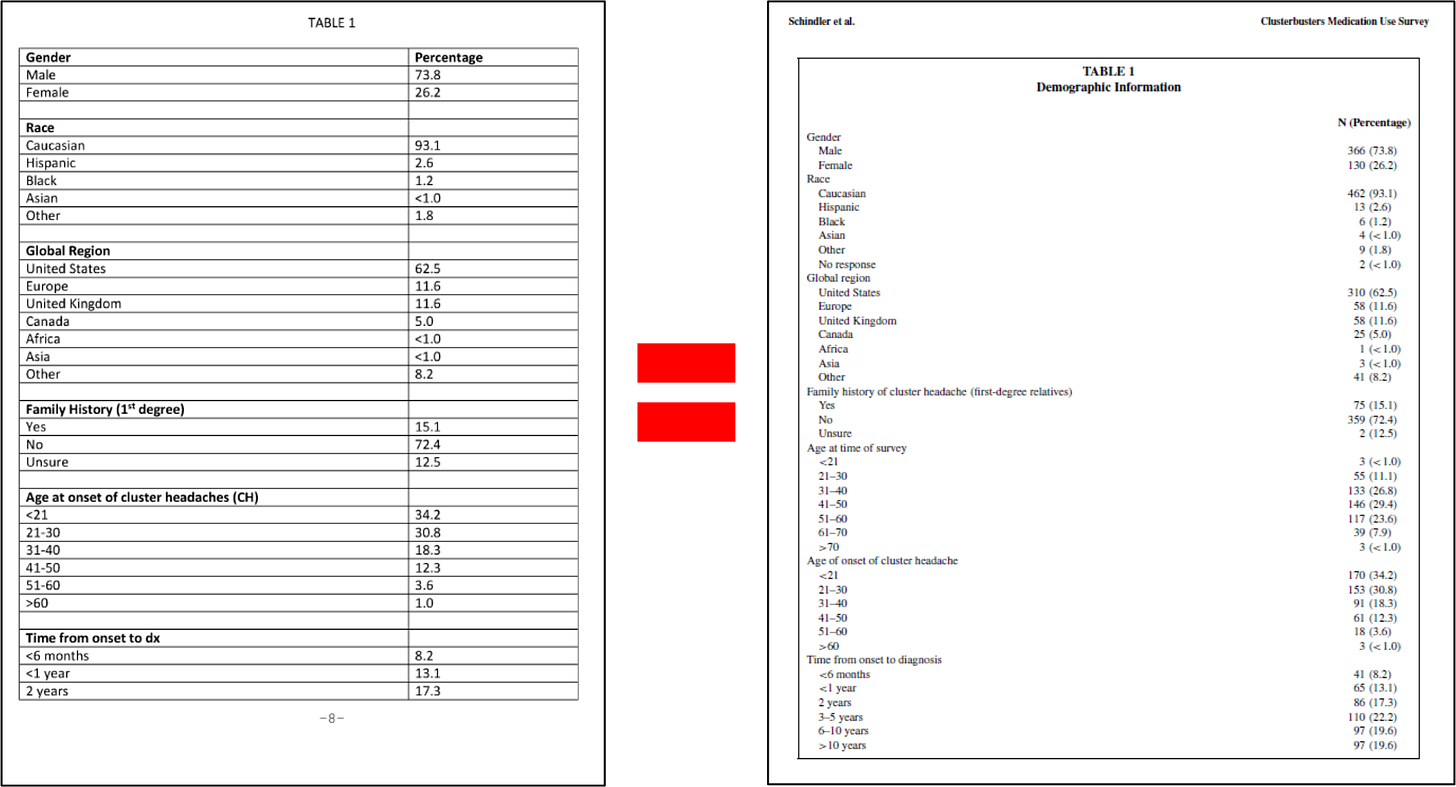

Example 1 is a medication use survey. The patent explains that researchers posed “41 questions pertaining to demographics, headache characteristics, toxic habits, medication use, and efficacy allowing for multiple choice and free-text answers.” “651 responders, 558 completed, and 496 with a verified diagnosis” provided answers. Figures 1 through 5 of the patent come from this survey, which show “that cluster headache patients reported greater clinical efficacy with psilocybin and other psychedelics as compared to conventional medications.” Remember that sentence.

Example 2 describes an exploratory study to investigate the effects of a single low dose of psilocybin in patients with migraine registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03341689) with approvals from the VA system and Yale University School of Medicine with an approved IND application #124,824. Psilocybin was provided by “author NC from the University of Wisconsin” and weight-based capsules of psilocybin .143 mg/kg and matching placebo were compounded into identical capsules. The patent then explains that the study showed “significant reductions in migraine headache burden in the two weeks after administration of a single low oral dose of psilocybin” and claims that this is a “novel finding for migraine headache.”

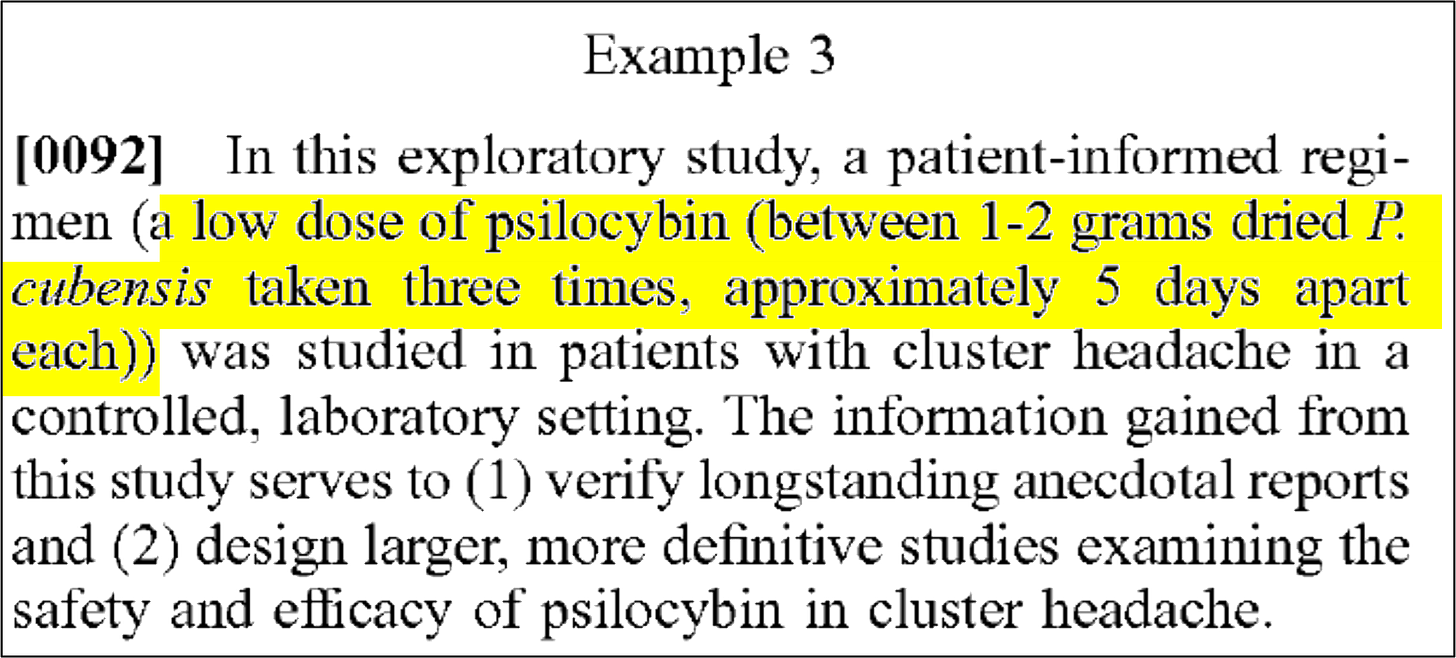

Example 3 similarly describes an exploratory study to investigate a low dose of psilocybin 1-2 grams dried P. cubensis taken three times, approximately 5 days apart. The study was also registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02981173). Participants were randomized and received either a “3-dose pulse regimen” of either psilocybin at .143 mg/kg or placebo. Each test day was separated by 5 +/- 2 days.

The Provisionals

Now that we’re through the spec, let’s return to the provisionals. Despite having three provisionals, the Schindler Application only claims priority back to one—the 2/2/2020 provisional. We see that priority claim in paragraph [0001].

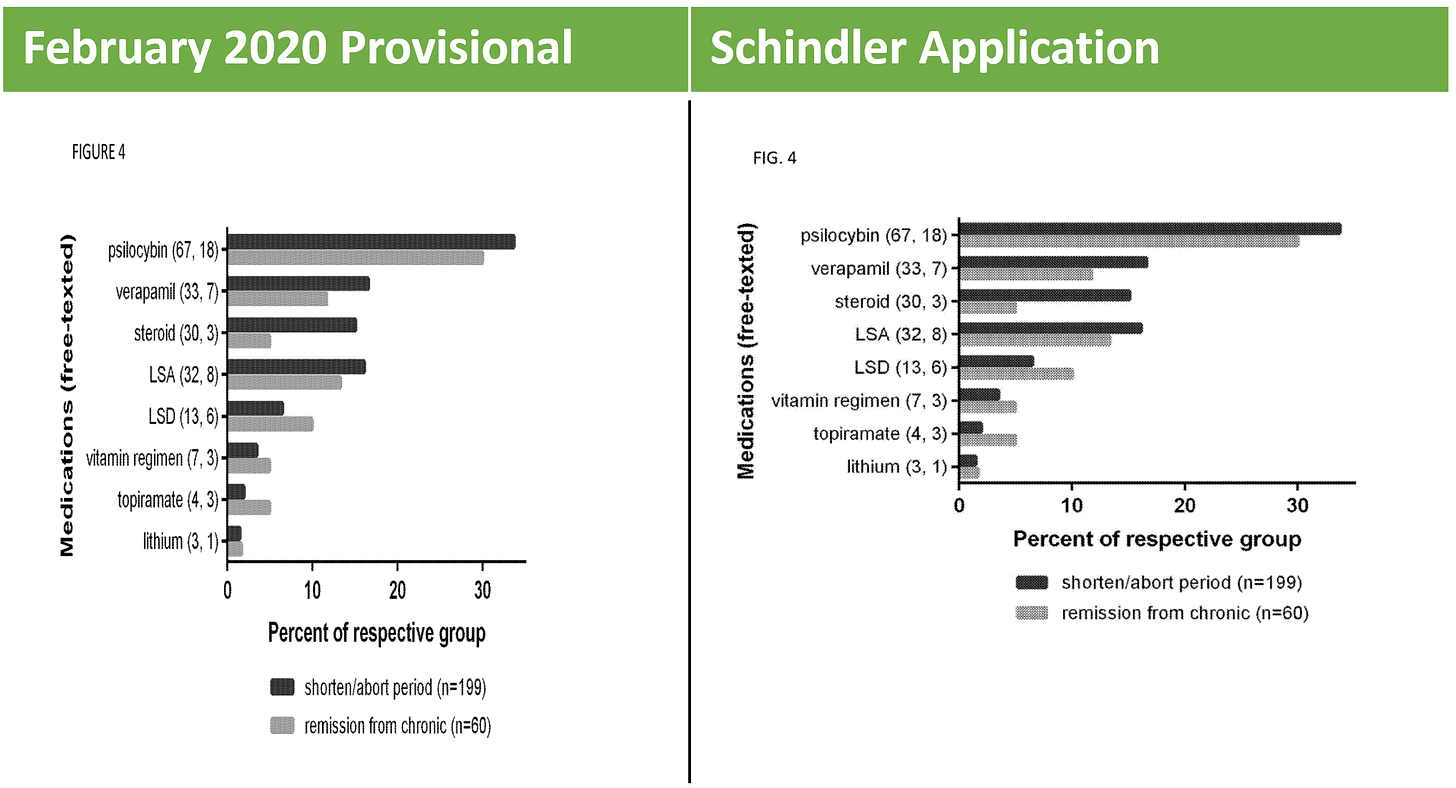

As discussed above, for this priority claim to be effective, the February 2020 provisional must fully support the claims. So let’s take a look. What we see is that the February 2020 Provisional is substantively identical to Example 1 in the specification, and therefore, provides support for Example 1 and claims tied to Example 1. Take, for example, Figure 4 of the provisional and Schindler Application:

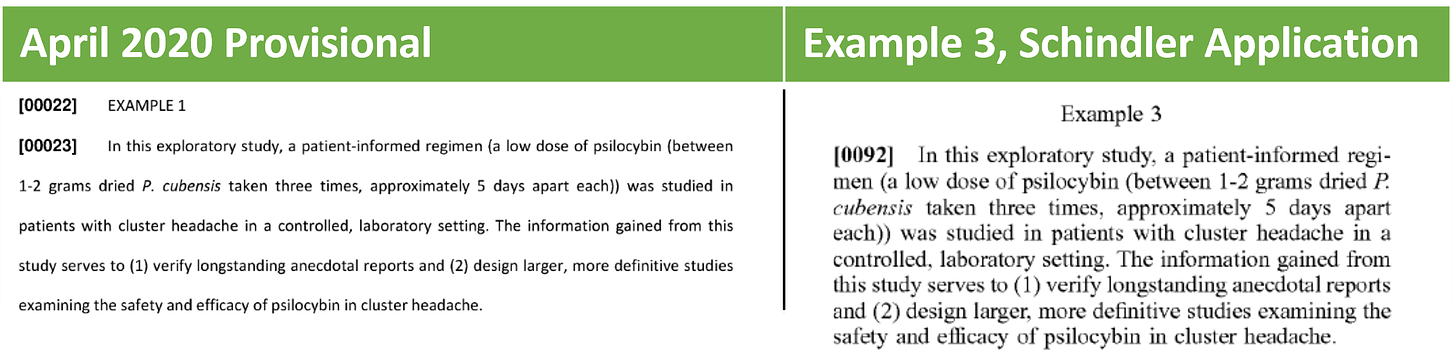

Not surprisingly, the other two provisional applications (April and May 2020) follow suit. The May 2020 provisional matches to Example 2 and the April 2020 provisional matches up to the exploratory study described in Example 3:

Everything is kosher so far. There is nothing improper about incorporating material from the provisional into the non-provisional. Indeed that is the entire point of a provisional.

But copying prior art into the provisional is another matter. And it turns out that the February 2020 Provisional and Example 1 are … you know the drill …

2015 Schindler

As noted above, the Schindler Application cites 2015 Schindler at the beginning of the specification when summarizing the prior art. Because 2015 Schindler was published in 2015, there can be no dispute 2015 Schindler is prior art.

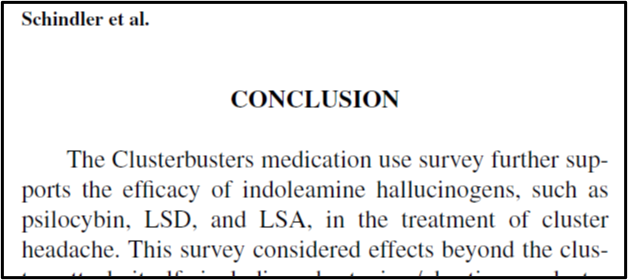

2015 Schindler is a paywalled article entitled “Indoleamine Hallucinogens in Cluster Headache: Results of the Clusterbusters Medication Use Survey” by a number of authors including the named inventors of the Schindler Application and several others, including Christopher Gottschalk. Thanks to our paid subscribers, this $47.00 expenditure is on us.

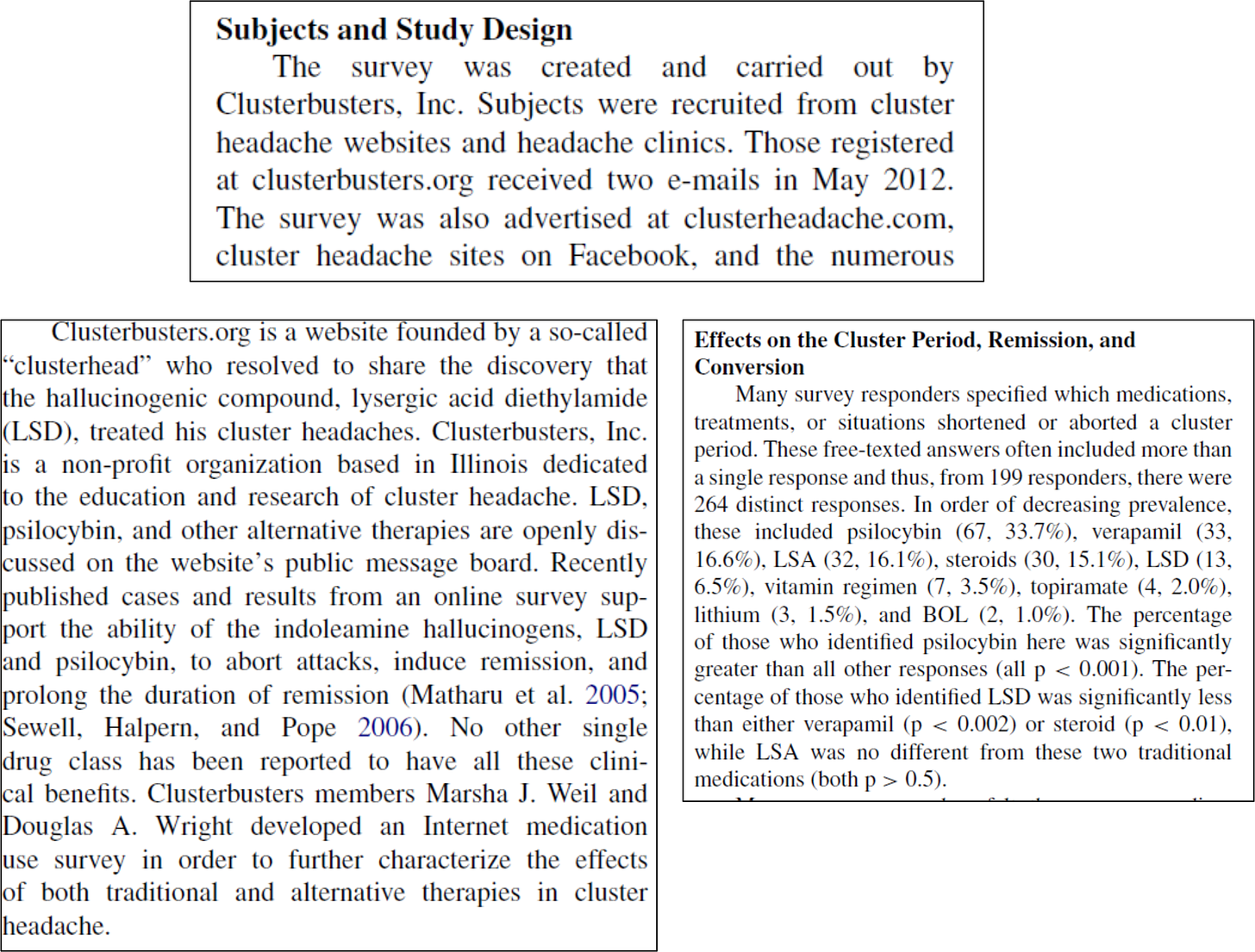

In brief, 2015 Schindler discusses the methodology and results of a survey created and carried out by Clusterbusters, Inc. members and non-inventors Douglas Wright and Marsha Weil:

The results not only showed psilocybin to be effective, but shockingly effective. Of all treatments surveyed, psilocybin was the most effective treatment, including compared to legal prescription drugs. Around 90% of the surveyed members who used psilocybin found it to be at least partially effective in reducing symptoms.

Another prior art reference, the 2006 Sewell survey, reports similar efficacy. In that survey, psilocybin was able to abort cluster headache attacks in 22 out of 26 patients and had a preventative effect in 90% of patients.

It is the results of the Clusterbusters, Inc. survey that the 2020 Provisional and the Schindler Application use as written description to support the claims. There can be no doubt. The two describe the exact same cohort of study participants.

Figures 1 through 5 of the Schindler Application? All come from 2015 Schindler. For example, the data depicted in Figure 4 shown above comes straight from the discussion in 2015 Schindler on “Effects on the Cluster Period, Remission, and Conversion.”

The claims also read right out of 2015 Schindler. It is commonly known in the art that while psilocybin content in dried mushrooms varies, they have a psilocybin content roughly equal to approximately 1% of dry weight. The 1-50 mg in the application corresponds to the .1 to 5 gram weights collected in the survey.

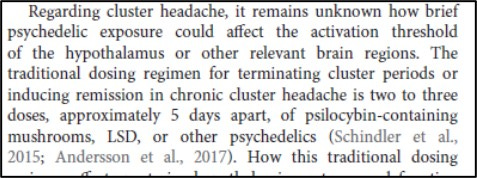

Three years later, in 2018 Schindler, the researchers would cite 2015 Schindler to explain that the “traditional dosing regimen for terminating cluster periods or inducing remission in chronic cluster headaches” is “two to three doses, approximately 5 days apart.”

Or maybe you are a video person. If so, here is a 30 minute video of Dr. Schindler presenting on 2015 Schindler at Psychedelic Science 2017. (The video is also prior art.) Skip to 11:00 to hear about “a number” of surveys and case reports of psychedelic use in headaches.

Schindler goes on to explain at 14:30, “It is not too surprising that psilocybin and LSD and such compounds would be effective in treating cluster headache. They are structurally similar to some compounds that are relevant.” At 20:10, she discusses the clinical trials that she will run at Yale to study cluster headaches. Notably, over a slide describing the “busting” regimen, Schindler explains the clinical trial: “what we’re essentially doing is, we’re pretty much replicating the regimen that cluster patients have already come up with.”

Clusterbusters.org (and Clusterbusters.com)

As Dr. Schindler and 2015 Schindler explain, Clusterbusters, Inc. carried out a survey of how its members were already using psilocybin and other psychedelics to abort or prevent headaches. That means not only is Schindler 2015 itself prior art, but it is a prior art that surveys the prior art. Prior art squared.

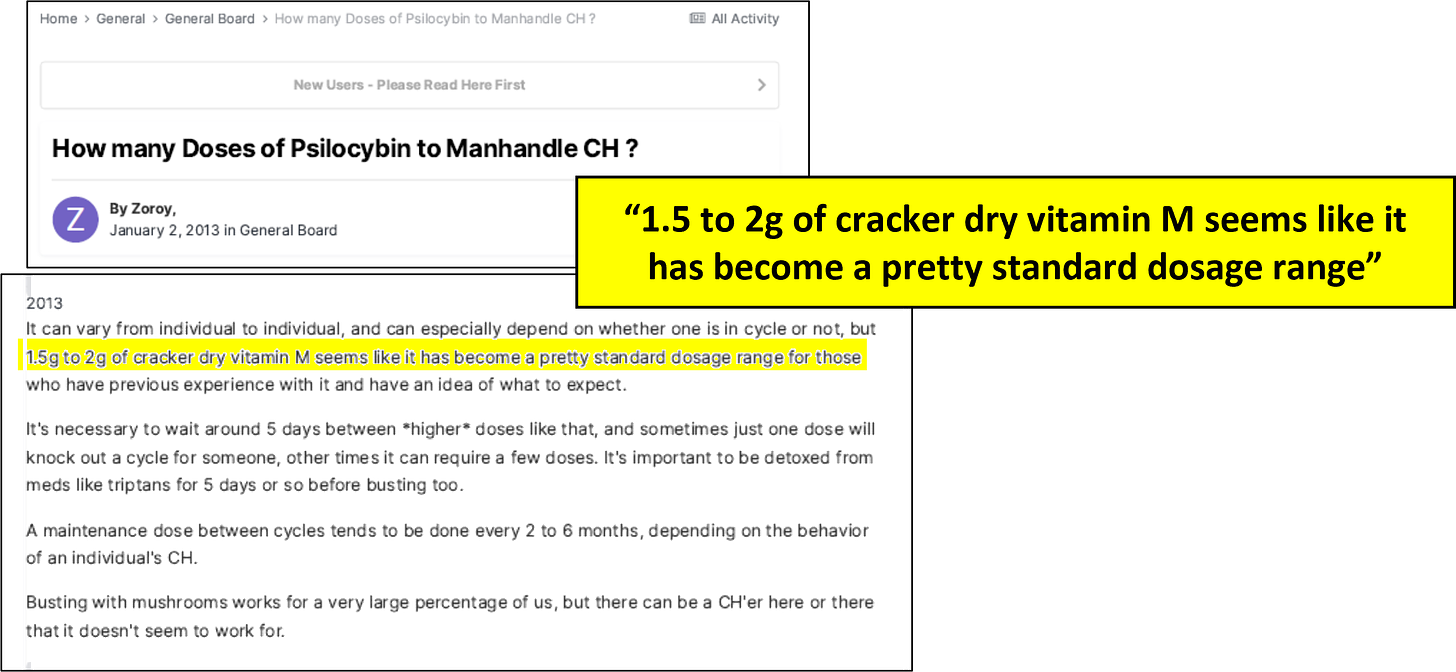

As noted in Schindler 2015, “LSD, psilocybin, and other alternative therapies are openly discussed on the website’s public message board.” Indeed, the Clusterbusters website has a forum that goes back almost a decade. And in that forum one can find a number of posts on dosing and protocols. Say you want to “manhandle” your cluster headaches. There is a January 2013 thread for that. The thread tells you to use “1.5 to 2g “cracker dry vitamin M” — the “standard dose range.”

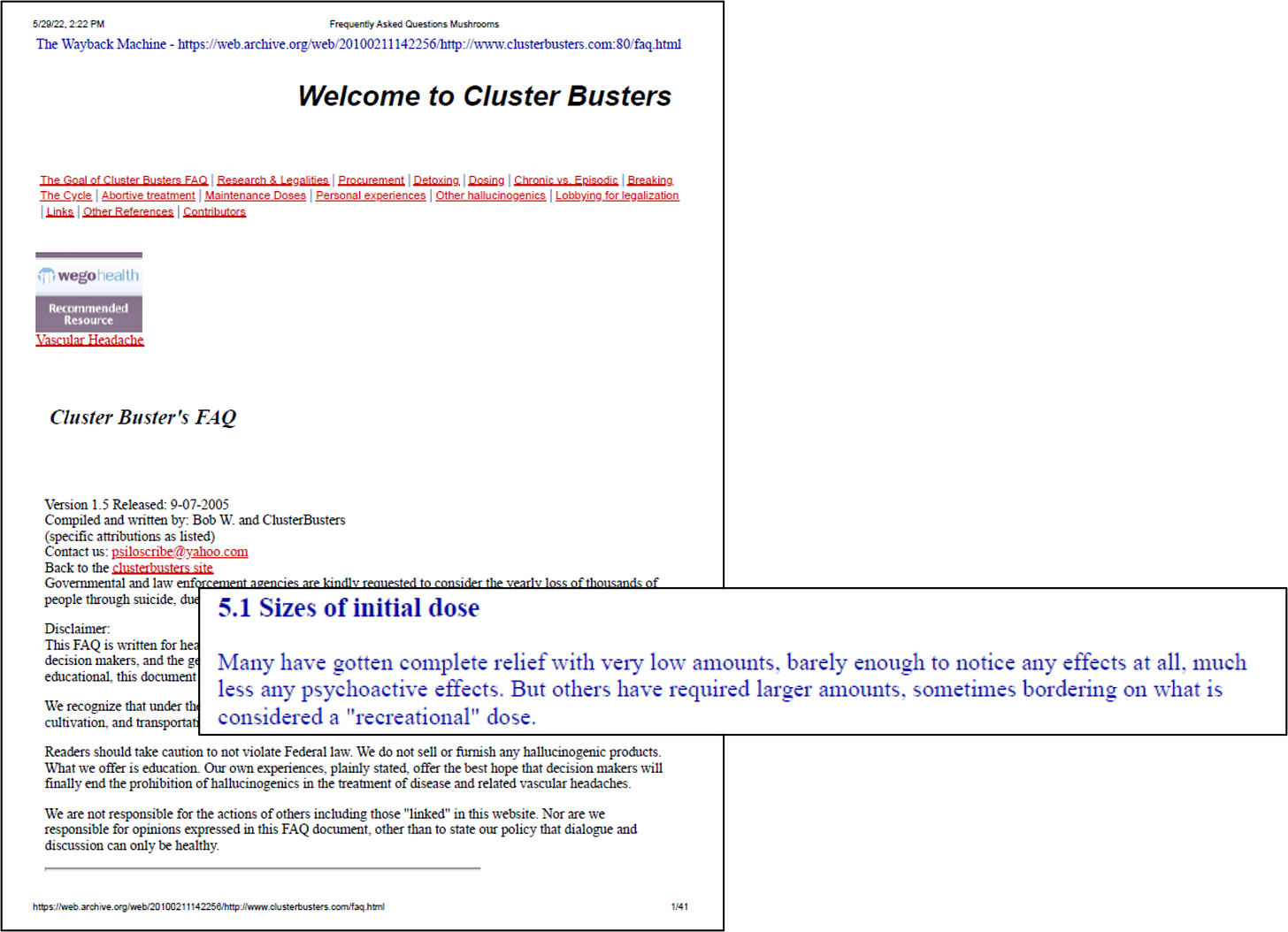

We can go back farther. Before ClusterBusters was located at clusterbusters.org, it was located at clusterbusters.com. Using the internet time machine, we can turn the clock back and find more information about folks using psychedelics to treat headaches and dosing protocols. For example, you can find Clusterbusters FAQ from Clusterbusters founder and president Bob Wold, published in 2005, which details everything from growing mushrooms in a bag to dosing:

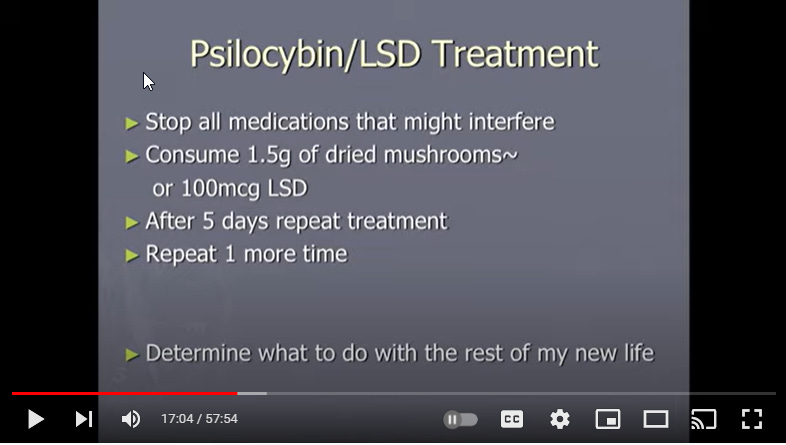

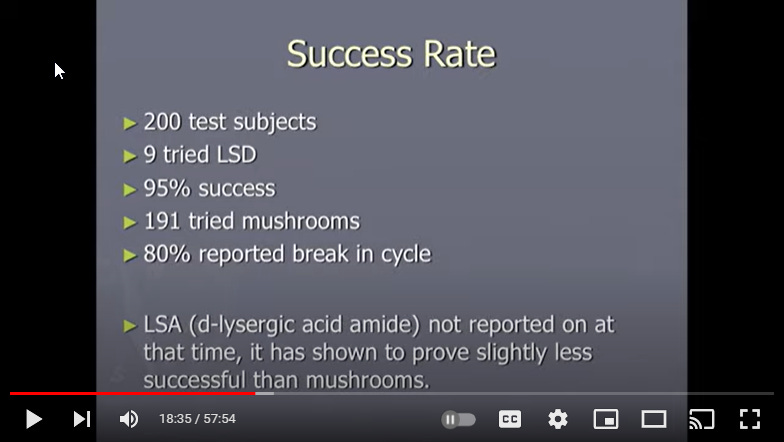

Or maybe you’re still a video person. In the following video (15:09) from July 2013 (also prior art), Wold explains his three doses, five days apart regimen:

Very low doses of psilocybin or LSD not only would abort a cluster headache, but in many cases it would completely stop the cycle in its tracks. So if you are looking at a 3 month cycle, you took it two weeks in, it would end, rather than go on the entire three months. So that was the first big break for us, getting this actually published in Neurology, and we started building on that.

The treatment is first thing you need to do is stop all medication you have been using. What we did find was when people stopped the medication that they’ve been using for their clusters, their cluster cycles actually got better. Their headaches weren’t as intense. Some of them went from 3 a day to 2 a day. So afraid as they were on stopping the medications that they were using, we’re actually finding that most of the medications were actually making their cycles worse and last longer.

The treatment consists of 3 doses, its not something you take every day. Each of the doses is actually very small. Usually a quarter of what would be a recreational dose. So, it’s not like you’re sitting at home counting the pink elephants in your room. You aren’t hallucinating. And most people report that the side effects from the dose are less than the medications that they have been using for years. Its three doses five days apart. And in many, many cases it will stop the entire cycle and not just the headaches for that day.

Or maybe you don’t have the attention span for 30-minute videos. If so, check out Tyler’s 2017 video.

Or hear about Lee Ann’s lifesaving discovery about “people using mushrooms.”

And I’d be remiss not to mention this 2007 episode of House where, citing “new research” (i.e., the 2006 Sewell study) the doctors give shrooms to the 16 year-old patient for his cluster headaches after he shouts “Need, shrooms, now!”:

I’ve made my point. There is no invention here. The prior art above — Schindler 2015, the Clusterbusters publications, and numerous public disclosures to and from the Clusterbuster community anticipate most if not all of the current claims — certainly the broader ones. Treating headaches with psychedelics according to any number of dosing regimens, while illegal, has been known, practiced, and openly spoken about for decades.

Examples 2 and 3

Example 1 is completely covered by the prior art. Actually, it is prior art. That means the only content in the Schindler Application that is plausibly original is the clinical trials described Examples 2 and 3. Here, however, the Schindler Application runs into two more problems.

First, the clinicaltrials.gov site might be prior art. Recently, in a few Inter Partes Review proceedings,3 the Patent Office has been citing postings on clinicaltrials.gov as prior art. For example, in Fresenius v. Chugai, the Patent Office concluded that the petitioners demonstrated a reasonable likelihood that they would prevail in showing that a claim directed to “An article of manufacture comprising a subcutaneous administration device, which contains and delivers to a patient a 162 mg fixed dose of tocilizumab” was anticipated by clincaltrials.gov posting, NCT0965653, which disclosed a clinical trial where patients would “be randomized to receive tocilizumab 162 mg sc [subcutaneously] either weekly or every other week, in combination with methotrexate, for 12 weeks.”

With postings on clinicaltrials.gov that go back to 2017, long before the priority date, the Schindler Application has a similar incurable problem. On the clinicaltrials.gov website, we see a dose amount of 0.143 mg/kg Psilocybin or 10 mg Psilocybin. And for good measure, you can go to the “History of Changes” link and pull up what the record looked like going back to November 30, 2016. The exact dosing regimen of 0.143 mg/kg Psilocybin, three test days, five days apart is disclosed.

Beyond that, as Dr. Schindler herself said, the clinical trial in Example 3 “replicat[ed] the regimen that cluster patients have already come up with.” “Replicated” doesn’t sound new or non-obvious to me. And clearly it isn’t. .143 mg / kg isn’t a randomly chosen dose. It is decimal short-hand for 1 mg / 7 kg or 10 mg/ 70 kg—a standard low-grade but effective dose of psilocybin that has been studied by those in the art. For example, in the 2018 Barrett al. article entitled “Double-blind comparison of the two hallucinogens psilocybin and dextromethorphan: similarities and differences in subjective experiences,” researchers examined 10 mg/kg and found that 10 mg/70kg psilocybin induced many of the positive effects of psilocybin with low chances of negative effects:

It is not enough that a claim lay out something new in an anticipatory sense of having never been done or disclosed. Under 35 U.S.C. § 103, a claim also has to be non-obvious. And here, the Schindler Application falls flat on its face.

Obviousness is a fuzzy standard. But in light of 2015 Schindler and all the other prior art, it should be a complete bar to a patent here. In Warner Chilcott v. Teva, for example, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals—sometimes called the de facto “Supreme Court of patents”—concluded that claims directed to the monthly administration of Actonel 150 mg tablet were obvious. The patentee argued that it was arguable as to whether a person of ordinary skill in the art would have reasonably expected that dosing 150 mg of Actonel once monthly would be safe and effective. The Federal Circuit rejected the argument, noting that the prior art provided an express motivation to pursue the claimed monthly regimen and a reasonable expectation of success in doing so.

In light of the above disclosures, even assuming the .143 mg / kg or other dosing regimen were not new or disclosed, this isn’t a close case. 2015 Schindler tells the reader repeatedly that there would be a reasonable expectation of success. For example, it is the very first sentence of its conclusion:

The conclusion continues to note that (1) the survey demonstrated that psilocybin demonstrated relief with moderate and infrequent use (2) the work follows other studies showing safety and efficacy for other medical conditions and (3) a controlled study is needed to establish the effects in cluster headaches.

The authors of 2015 Schindler publicly stated the same thing. For example, here is a still from a YouTube video of author (not inventor) Gottschalk explaining that the prior art showed psilocybin to be 85% effective in treating cluster headaches:

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with using an original research paper to file a provisional patent within the time limits provided by the law. Nor is there anything improper with copying figures or text from a prior research publication into patent specification. This happens all the time. Filing for patents on a clinical trial is kosher. Filing prior art as the provisional patent application and then claim priority to that provisional is asinine. As is appropriating protocols and other information first generated and published on a website and internet forum.

*Sigh* This is getting old. We need to dig deeper.

The Origins of the Schindler Application

Few individuals have done more than Carey Turnbull to advance psychedelic science. Among other things, over the past decade he has:

Spent millions of his own money supporting psychedelic research initiatives at NYU, Johns Hopkins, and Yale.

Funded the seminal 2016 Ross Study.

Started B.More, a 501(c)(3) non-profit company to study psilocybin to treat patients suffering from Alcohol Use Disorder that is named after Brett Moore, who died of a drug overdose and was the brother of our co-founder, Claudia Turnbull.

Turnbull’s Ceruvia Lifesciences company offers LSD to researchers at no cost. There’s a good case to be made that Turnbull has advanced psychedelic science and made more contributions than any single philanthropist. It is hard to overstate his importance as a vanguard of the psychedelic renaissance.

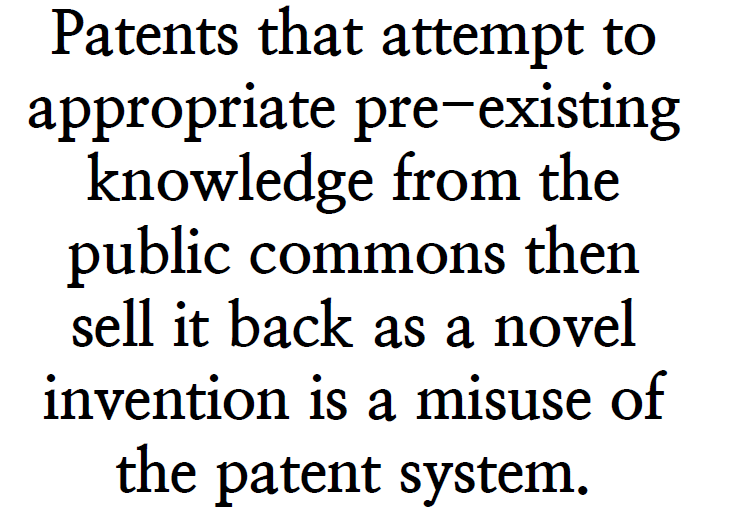

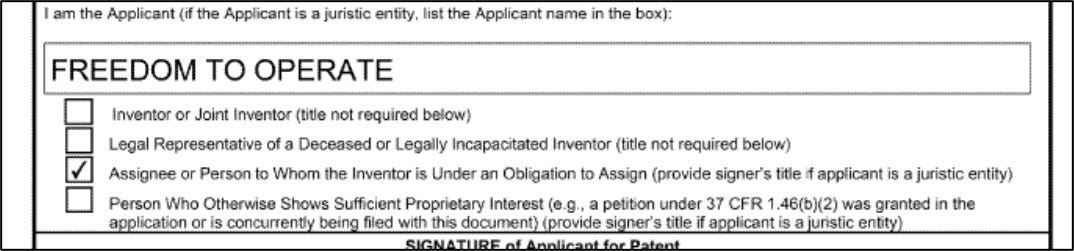

More recently, in 2021, he founded Freedom to Operate, or FTO, a non-profit dedicated to challenging flawed psychedelic patent claims and whose mantra on its front page reads:

Notably, FTO is leading the charge against challenging COMPASS’s suite of synthetic psilocybin patents. Protesting Compass’s decision to patent “Hydrate A,” Turnbull sent an open letter to COMPASS CEO George Goldsmith asking Compass to disclaim one of its patent or covenant that it won’t enforce the claims. And FTO is currently locking horns with COMPASS in patent office proceedings challenging the company’s issued patents on synthetic psilocybin. One article quotes Turnbull as stating that COMPASS is “attempting to patent things [it] should know [it] did not invent” and that “[p]atents are not a systemic fault of the system; bad patents that attempt to appropriate pre-existing knowledge from the public commons and then ransom it back to the human race are a misuse of that system.”

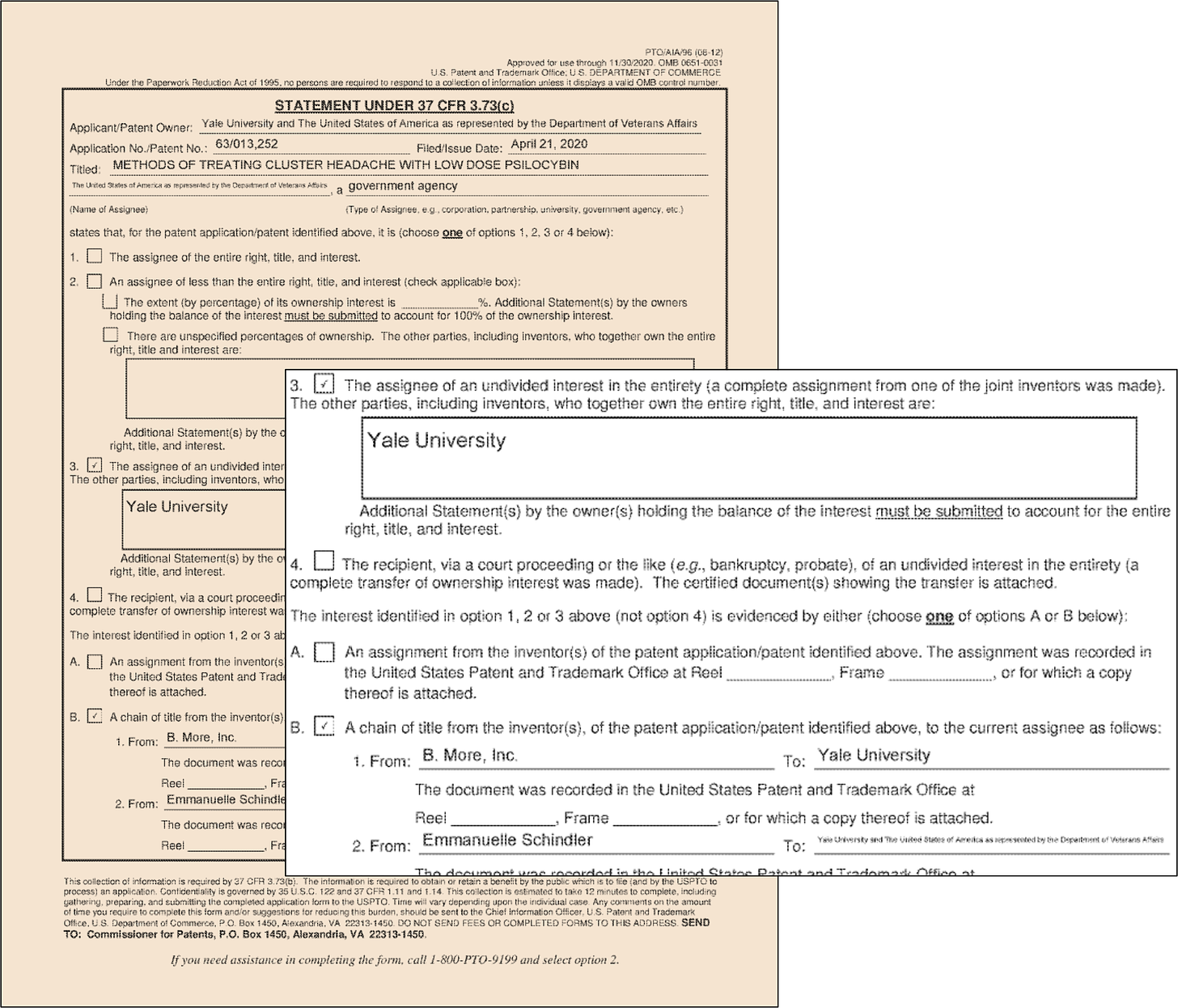

So as I was leafing through the provisionals, it came as a surprise to see that Turnbull and the groups he founded—including Freedom to Operate—filed the provisional applications to the Schindler Applications as assignees:

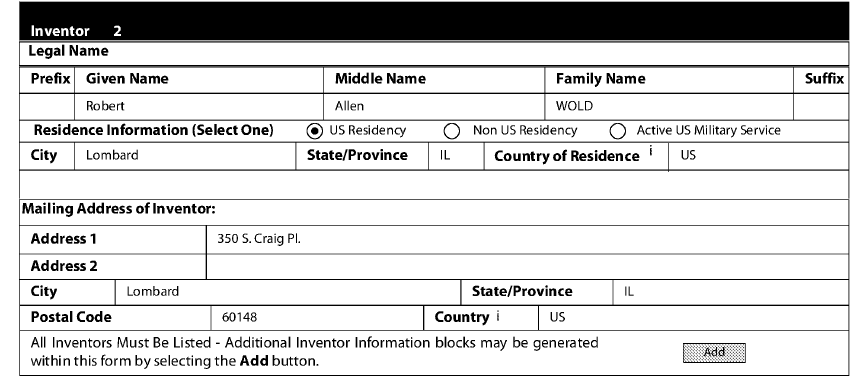

I noticed another oddity: inventorship. In Fall 2020, the April 2020 provisional—the one corresponding Example 3, the clinical trial of the “patient-informed” regimen—named Wold, the Clusterbusters founder, as Inventor #2 along with Dr. Schindler:

This makes some sense. The “patient-informed regimen” the specification in Example 3 appears to be Wold’s regimen. Legally, “conception is the touchstone of inventorship,” described as “the formation in the mind of the inventor, of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention, as it is hereafter to be applied in practice.” Performing a clinical trial that carries out a method of treatment is different from inventing or conceiving of the method. If any one person conceived of the “patient-informed” method disclosed in Example 3, it may have been Wold.

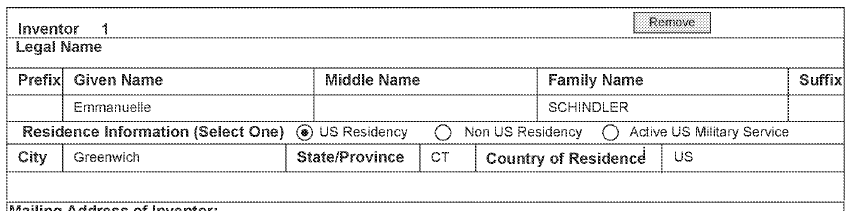

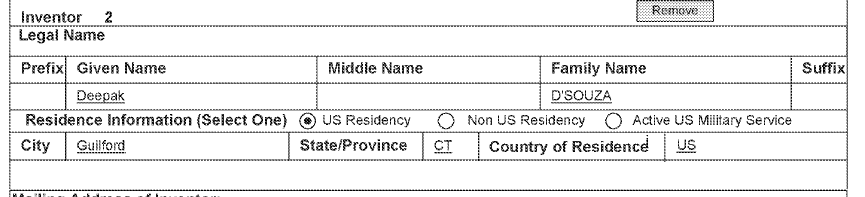

But on March 19, 2021, Wold disappears as an inventor, leaving just Schindler:

Right around the same time, on March 16—a little over a month after filing the non-provisional application—Schindler and Deepak D’Souza assign their rights as inventors to Yale and the VA:

And on March 19, in the April 2020 provisional, a filing notifies the Patent Office that Schindler assigned her rights to the Schindler Application back to Yale and the VA:

Then, a little over a week later, Schindler’s co-researcher at Yale Deepak D’Souza is named as a co-inventor to the April 2020 Provisional:

Without more facts, I can only speculate as to what is happening here. Suffice to say, each co-inventor on a patent application is a joint owner.

There’s another oddity too. In February 2022, a third party submission was made on the Schindler Application … by Porta Sophia, the Psychedelic Prior Art Library help built to help the patent office handle and reject patent applications like the Schindler Application:

Turnbull is on record as stating “I know this to be true: there can be no patent on psilocybin as a substance, nor on the known methods for making it or using it medically.” But as shown above, the Schindler Application seeks patent claims on a known or obvious method of using psilocybin medically. Not even close… On to Part 2.

There is a legal doctrine called the “doctrine of equivalents” where a party can be liable for infringement even though that party does not infringe every limitation of a patent claim.

I found this sentence to be so interesting that I Googled it. Emphasizing the unoriginal nature of this portion of the patent, turns out this phrase appears in many patents. Indeed, paragraphs [0036] to [0042] of the Schindler Application appears to be a standard insert, identical or near-identical to the text from Columns 4 and 5 of this patent and probably others too.

Inter partes review is a trial proceeding conducted at the Patent Office to review the patentability of patent claims only on anticipation or obviousness grounds, and only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.

Another awesome breakdown! I don't fully get what the specific involvement is of Turnbull and Porta Sofia, is there anything more you can say about that?

My reading is now that they willingly signed onto the application, but that would soap opera level of weird right?

Thank you for this deeply reported post.