This short essay briefly explores the issue of mescaline containing cacti and advances an argument that non-Peyote mescaline containing cacti may not be scheduled. Same caution: not legal advice.

Let’s jump right in.

Peyote

Peyote or lophophora williamsii is a mescaline containing cactus with a long history of Native American sacramental use.

Federal attempts to control peyote use are far more recent, but have a history as well. Federal control efforts began more than 100 years ago with William “Pussyfoot” Johnson. In 1906, Pussyfoot was appointed a special officer by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to suppress liquor consumption on reservations. Soon after, Pussyfoot set his eyes on new target: peyote. He sought to suppress peyote use the old-fashioned way. In 1909, he bought up all the available peyote in Laredo (around 176,400 buttons). And then he set it all on fire.

By 1929, federal law classified “peyote and its various forms” as a “habit-forming narcotic drug” in legislation to establish two “narcotic farms” – institutions to confine and treat drug users that committed federal offenses. These early controls were somewhat piecemeal, spread out over different federal agencies. But come the Second World War, federal attempts at peyote control were largely abandoned. Control reverted to the states.

Modern federal control of peyote begins with the Drug Abuse Control Amendments of 1965. That legislation defined “depressant and stimulant drugs” to include “drugs with hallucinogenic effects,” and established controls over their manufacture, possession, use, and sale. Soon after, the federal government brought peyote under the control by regulation under the Amendments.

The Controlled Substances Act—which in 1970 replaced the Amendments and consolidated federal drug law under one roof—classifies peyote as a schedule I drug. But under a regulation promulgated shortly after the CSA’s enactment, 21 C.F.R. § 1307.31, the Schedule I listing of “peyote” does not include ceremonial use:

The listing of peyote as a controlled substance in Schedule I does not apply to the nondrug use of peyote in bona fide religious ceremonies of the Native American Church, and members of the Native American Church so using peyote are exempt from registration. Any person who manufactures peyote for or distributes peyote to the Native American Church, however, is required to obtain registration annually and to comply with all other requirements of law.

It is important to note that this exemption stands apart from and predates the Religious Freedom for Restoration Act. It is a DEA interpretive rule about what “peyote” means in the CSA.

In Kennedy v. Bureau of Narcotics & Dangerous Drugs, the Church of the Awakening petitioned the federal government to amend the peyote regulation to exempt religious use of Peyote by the Church of the Awakening. The Church contended that the regulation was unconstitutional because it arbitrarily distinguished between the Native American Church and other religious organization. The government conceded that the Church was a valid religious organization and that church members used peyote in bona fide religious ceremonies; but it justified the regulation by arguing that peyote use was not as central to the ceremonies of the Church as it was to the Native American Church. The Ninth Circuit rejected the argument, however, noting that it made no constitutional difference because those distinctions did not have a rational relationship to the legitimate governmental interest or interests to be served by the challenged regulation: the protection of the health of the citizens by controlling the manufacture, sale, and use of dangerous or potentially dangerous drugs. The court could not “say that the Government’s interest in a church member's health increases or diminishes depending upon whether his ingestion of a dangerous drug is of greater or lesser importance in the religious ceremonies of his church.” Thus, the court concluded that the exemption regulation created an arbitrary classification that did not withstand substantive due process attack.

Nonetheless, the effort to expand the regulation failed because the Church’s regulation suffered the same constitutional infirmity—namely, creating a special classification for the Church of the Awakening and the Native American Church.

Four years later, Alan Birnbaum founded the Native American Church of New York, an organization unaffiliated with the Native American Church. The New York Church’s beliefs included that all psychedelic drugs, including peyote, are deities. Birnbaum then petitioned DEA to exempt the use of all psychedelic drugs in religious ceremonies of all churches. The DEA denied Birnbaum’s petition, prompting the Native American Church of New York to sue.

The district court in Native Am. Church of New York v. United States, quickly dispatched Birnbaum’s claims relating to drugs other than peyote. But it concluded that the exemption for peyote was “equally available to the plaintiff” if it were a bona fide religious organization and would make use of peyote for sacramental purposes and regard the drug as a deity. After trial, the court found that Birnbaum’s church was not a bona fide religious organization. Hence, no exemption.

Around the same time as Birnbaum’s campaign, DEA reached out to the Office of Legal Counsel to examine three issues arising with the peyote exemption: (1) what is its scope; (2) is it constitutional; and (3) could DEA constitutionally exempt only American Indian peyotists to the exclusion of other religious users of the drug. In an opinion authored by famed litigator Ted Olson, OLC concluded that:

Congress intended to exempt peyote use not just by the NAC, but other bona fide peyote-using religions in which the use of peyote is central to established religious beliefs, practices, dogmas, or rituals;

That the exemption was constitutional; and

Limiting the exemption to American Indian peyotists might violate the Establishment Clause.

OLC also concluded that limiting the exemption to the Native American Church would require statutory amendment, since the current statutory exemption applies to the NAC and to other religions whose use of peyote is central to established religious beliefs, practices, dogmas, or rituals. According to OLC, under the current statutory scheme, DEA was obligated to accord the exception to any that could establish that use of peyote is central to established religious beliefs, practices, dogmas, or rituals.

With the American Indian Religious Freedom Act Amendments of 1994, Congress codified the peyote exception for members of Indian Tribes.1 Moreover, RFRA, as amended by the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, largely eliminates the need for a peyote exemption. But to date, this exemption remains on the books. And as I next explain, it could have minor interpretive significance.

Non-Peyote Mescaline Cacti

In my essay on psilocybin mushrooms, I explained an argument that psilocybin mushrooms are not controlled substances. In short, Congress never placed psilocybe mushrooms on the schedules, only psilocybin. We assume mushrooms are controlled because they contain psilocybin, but this assumption isn’t immune to question.

That same argument holds true for non-peyote mescaline cacti. Peyote is on the schedules. But other mescaline cacti, such as the San Pedro cactus (Echinopsis pachanoi), are not.

Beyond this argument, there is another reason one could say that a mescaline containing cactus other than peyote is not federally controlled. And that reason is whether the listing of “mescaline” in Schedule I includes organic mescaline contained in a cactus. Applying the logic of Hemp Indus. Ass’n v. DEA, 333 F.3d 1082 (9th Cir. 2003) (“Hemp I”) and Hemp Indus. Ass'n. v. DEA, 357 F.3d 1012 (9th Cir. 2004) (“Hemp II”), it does not.

Neither case deals with mescaline, but “tetrahydrocannabinols.” In 2001, DEA sought to ban consumable products containing hemp oil, cake, or seed through rulemaking. The agency claimed that “tetrahydrocannabinols” in the schedules included organic THC in the cannabis plant. The Ninth Circuit disagreed and held that the listing of THC in the schedules encompassed synthetic THC, but not organic THC in a cannabis plant.2 If THC is controlled, it is controlled through the statutory definition of “marihuana”:

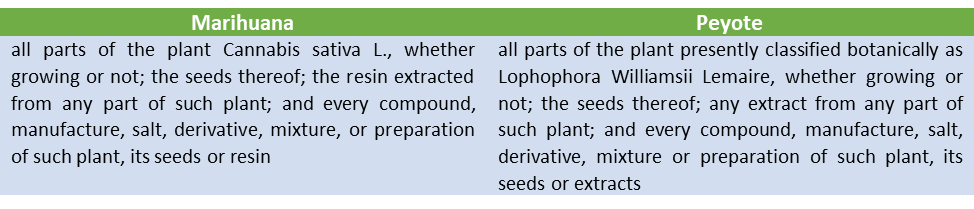

all parts of the plant Cannabis sativa L., whether growing or not; the seeds thereof; the resin extracted from any part of such plant; and every compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, mixture, or preparation of such plant, its seeds or resin

Bottom line: the “[t]he CSA lists marijuana and THC separately on Schedule I.” The First Circuit in United States v. McMahon, 861 F. 2d 8 (1st Cir. 1988) described this as the “organic-synthetic distinction in Schedule I.”

This “organic-synthetic distinction” makes sense in light of CSA’s history. As the schedules were being crafted, THC was known to be the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana. It was also known that THC could be produced synthetically. The listing of THC reflected a judgment that synthetic THC should be controlled in addition to marijuana. In an August 1968 predecessor regulation to the CSA, DEA’s predecessor, the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, listed “[s]ynthetic equivalents” of tetrahydrocannabinols in the cannabis plant. When Congress passed the CSA in 1970, it carried over that regulation into the statute. The Ninth Circuit thus concluded that DEA’s interpretation of THC to include naturally occurring THC was “specious” because it would “render superfluous the separate listing of marijuana and would nullify the explicit exemption of hemp seed and oil from the coverage of marijuana.”

A similar argument could be made for peyote and mescaline. Assume that cacti containing mescaline are “materials” containing controlled substances—a proposition I do not necessarily agree with. If so, then if “mescaline” in Schedule I includes organic mescaline naturally contained in cacti, the separate listing of peyote would be superfluous. Like marihuana/THC, because peyote/mescaline are listed separately in the schedules (21 C.F.R. § 1308.11(d)(26)).

The similarities between marijuana/tetrahydrocannabinols and peyote/mescaline runs deeper. In a statement of policy and interpretation published in the Federal Register published in April 1975, DEA explained that “peyote” includes not only the lophophora williamsii plant, but all derivatives and extracts from the plan, including mescaline:

Peyote means “all parts of the plant presently classified botanically as Lophophora Williamsii Lemaire, whether growing or not; the seeds thereof; any extract from any part of such plant; and every compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, mixture or preparation of such plant, its seeds or extracts.”

Sound familiar? The statutory definition of peyote uses almost the same language as the statutory definition for marihuana, which suggests it shouldn’t operate differently.

Lest there be doubt, shortly after DEA amended the regulatory definition of “peyote,” on page 124 in the Summer 1975 issue of Drug Enforcement (available on Google Play), DEA’s Office of Chief counsel wrote that the 1975 regulatory definition reflected “existing law.”

Two more points.

First, as was the case with THC in 1970, mescaline was known (1) to be the psychoactive ingredient in peyote and (2) that it could be produced synthetically. Indeed, mescaline is an OG: the first synthetic psychedelic, synthesized by Merck in 1919 and sold as mescaline sulfate shortly thereafter.

Second, to tie the essay together: reading “mescaline” to include organic mescaline would nullify the longstanding peyote exemption.

Recall in Part A above that the peyote regulation 21 C.F.R. § 1307.31 purports to interpret “peyote” in the schedules. It declares, “the listing of peyote does not apply to non-drug use in bona fide religious ceremonies of the Native American Church.” But if “mescaline” in the schedules includes organic mescaline found in naturally occurring cacti—including peyote—then this longstanding exemption becomes meaningless. While those engaged in bona fide non-drug religious practice with peyote may not be using a controlled substance named “peyote,” if mescaline includes organic mescaline, they would be using a “material” (the cactus) containing organic “mescaline.”

One counterpoint here must be acknowledged: unlike the statutory definition of “marihuana,” the regulatory definition of “peyote” does not exclude any part of the peyote cactus. This distinction is not insignificant, and it was part of the reasoning that lead the Ninth Circuit to conclude that “tetrahydrocannabinols” listed in the schedules included only synthetic tetrahydrocannabinols. Indeed, in court, perhaps that distinction may be dispositive.

Conclusion

Just as organic THC is controlled through the definition of marihuana, not THC (HIA I, HIA II); one could argue that organic mescaline is controlled through the definition of peyote, not mescaline. And if that’s the case, a mescaline containing cactus other than peyote that contains organic mescaline isn’t controlled, because it isn’t peyote.

Once again, despite the textualist and historical appeal of this theory, I wouldn’t count on it prevailing in court. At least, not yet. Therefore, this is not legal advice of any kind.

I seriously question the constitutionality of laws like 21 U.S.C. 1996a and Section 481.111(a) of Vernon’s Texas Health and Safety Code, for two reasons. First, these laws discriminate based on race; second, as discussed in the Olsen memo, limiting the exemption to Indian religious ceremonies implicates the Establishment Clause.

Other cases agree that the listing of THC in Schedule I is limited to synthetic THC, for example, United States v. Wuco, 535 F.3d 1200 (9th Cir. 1976).