A brand new antidepressant with a hallucinogenic ingredient is “set to disrupt the multi-billion dollar mental health market.” This new drug purports to be “the first and only rapid-acting oral antidepressant whose effects show at one week.” Even more, it has a new mechanism of action approved for major depressive disorder—the first in over 60 years.

Sorry, Microdosers1, COMPASS brahs, and plant shamans. I’m not referring to psilocybin, natural or synthetic. No, something far better:

While you were tripping (pun intended) over the Phase IIb COMP360 psilocybin results, Axsome stockholders were minting money off the release of Auvelity™, which had an even better Phase III showing. The best part? Classic Big Pharma play.

Top-to-bottom Auvelity™ is profoundly unoriginal. The drug itself is a mash-up of two fixed doses of long-known ingredients (1) dextromethorphan (DXM or DM), a common ingredient in over-the-counter (OTC) cough syrup and (2) bupropion, better known as the antidepressant and smoking cessation aid Wellbutrin™. This is not a drug you take in a clinic for hours with therapeutic support. No new infrastructure needed. Auvelity™ is traditional pill-a-day pharma. The cost? $500+ for a monthly supply. (Note: 45mg DXM (3 15mg capsules) and 100mg bupropion purchased separately cost $20).

Little wonder Axsome’s market cap—attributable in large part to the expected $1+ billion revenue from Auvelity™—ballooned to equal around the entire public-psychedelic sector combined. For the visually inclined:

This rest of this essay explores the pharmacology and regulatory history of the substance underlying Axsome’s success: DXM.

About DXM

First patented in 1949 by Hoffman La Roche, FDA approved DXM in 1958 as a non-prescription, non-addictive antitussive. Today, one can purchase DXM at almost any drug store in America. DXM is the most common cough suppressant used in the United States in OTC medicines today.Per DEA, DXM

is a cough suppressor found in more than 100 over-the-counter (OTC) cold medications, either alone or in combination with other drugs such as analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen), antihistamines (e.g., chlorpheniramine), decongestants (e.g., pseudoephedrine), and/ or expectorants (e.g., guaifenesin).

At higher doses, DXM is also powerful dissociative—like ketamine and PCP. Indeed, research shows that animals do not discriminate between ketamine and PCP. At these higher doses, DXM can induce euphoria and visual and auditory hallucinations. Hence, robotripping, skittling, or dexing.

Pharmacology

DXM is a complex substance. Research and receptor binding studies show at least five pharmacological activities:

NMDA antagonism. Thought to be the primary mechanism of DXM and responsible for dissociative effects.

Sigma-1 receptor agonist. Many antidepressants and psychoactive drugs have sigma-1 activity.

Calcium channel blocker. Can be an antihypertensive and may contribute to neuroprotective effects.

Serotonin. Research shows that DXM has a high affinity for binding to the serotonin transporter. Hence, be careful mixing DXM cough syrups with SSRIs. Definitely don’t cook chicken in NyQuil.2

Nicotinergic antagonist. DXM administration may lead to fewer nicotine cravings.

DXM has a somewhat similar pharmacology to ketamine and PCP and may also produce similar antidepressant effects (hence Auvelity™). In animal drug discrimination studies, DXM generalizes for other NMDA-antagonist dissociative ketamine and PCP.

In this respect, DXM is also similar to ibogaine, another NMDA antagonist (dissociative) with a complex and fascinating pharmacology that interacts with many neurotransmitter systems, including the serotonin system.

At the serotonin transporter, DXM binds with high affinity producing serotonin reuptake inhibitory activity—a SERT blocker. One small monkey study even suggests that DXM may have neuroprotective effects on SERT levels after MDMA use.

Put simply, research suggests DXM acts on both the glutamate and serotonin systems, which happen to both be targets of other antidepressant, mood-stabilizing, and other psychiatric medications.

Importantly, while structurally related to the common opioid codeine, DXM does not have significant activity at mu-opioid receptors, the receptors responsible for the analgesic effects of opioids. DXM is not addictive.

This unique pharmacology led researchers in the 1990s to explore potential clinical applications for DXM beyond use as an OTC antitussive, including administering DXM for pain, as a neuroprotectant, and for neurodegenerative disorders. None bore fruit. Some research shows DXM might have a role in opioid withdrawal. More recently, DXM is an active ingredient in multiple approved pharmaceutical drugs.

In 2010, Avanir Pharmaceuticals brought Nuedexta, the only approved drug to treats psudobulbar affect or “emotional incontinence.” Nuedexta is a DXM/quinidine combination drug. The quinidine is DXM’s wingman: it merely inhibits the CYP2D6 liver enzyme that metabolizes DXM to increase plasma concentrations of DXM.

This past August, as noted in the intro, Axsome won approval for AXS-05 or Auvelity™ with an indication for Major Depressive Disorder. While the drug is nothing more than a fixed combination of DXM/bupropion—two well-known ingredients—it is protected by 100+ U.S. Patents such as this.

[Aside: Axsome has an entire suite of research based on DXM/bupropion. AXS-05 is currently being developed for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease agitation and smoking cessation. The drug received Breakthrough Therapy designation from FDA for Alzheimer's disease agitation.]

[Second Aside: As promised, Matt presents patents is paywall released.]

Of course, not everyone is high on DXM. Johns Hopkins researchers compared psilocybin to DXM and published a paper in 2018. They concluded that psilocybin produced relatively greater visual, mystical-type, insightful, and musical experiences, while DXM producing greater disembodiment.3 An earlier Johns Hopkins study suggests that high doses of DXM produces effects similar to classic hallucinogens.

A Unique Regulatory History

DXM is an abused drug. Consider the following snapshots from U.S. Department of Justice’s October 2004 Intelligence Bulletin:

The type of rhetoric used in the Bulletin suggests DXM is no different from other controlled drugs of abuse like MDMA, methamphetamine, or opiates.

But it is isn’t. DXM is sold over-the-counter. How and why did a powerful hallucinogen evade prohibition and become easily available for purchase OTC? Chalk it up to a unique regulatory history and its role as a putative non-addictive antitussive.

FDA Regulation

Up to the 1950s, codeine cough syrup prevailed as the main antitussive. Codeine, of course, is an opioid with addictive properties. Researchers sought nonaddictive alternatives. Enter DXM, which FDA approved in 1958. Notably, the law in 1958 did not require the same safety/efficacy trials the FDA requires today.

By 1972, while marketed DXM cough syrups had been shown to be safe/effective in the main, well-controlled studies studies of the efficacy of DXM cough syrup were still “not available.” Indeed, while evidence shows DXM’s efficacy, that evidence is weak when compared to efficacy evidence backing the New Drug Applications for other pharmaceuticals.

OTC DXM products are regulated under the monograph system.

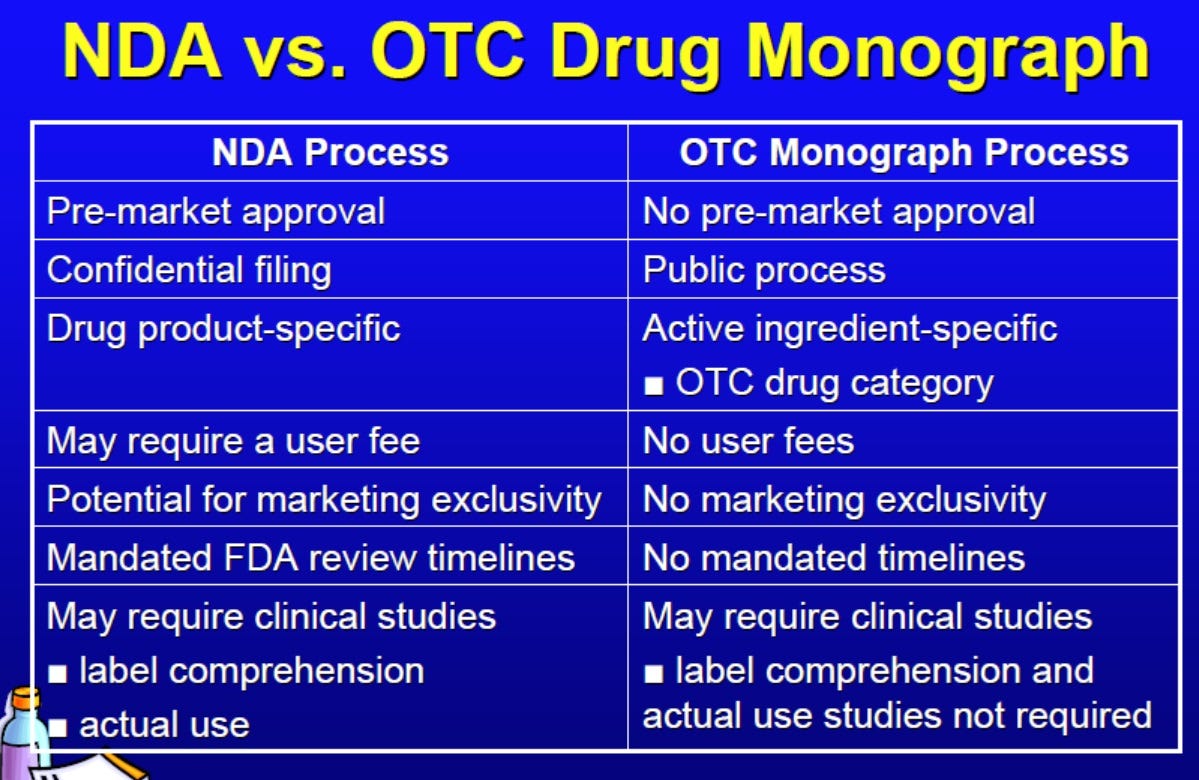

Unlike NDAs, monograph drugs do not require prior FDA approval before marketing. As shown in the table above, companies can market a drug product under the monograph system if (1) the active ingredient is listed in a monograph and (2) the product is listed as stated in the monograph.

In 1976, FDA posted an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking entitled “Establishment of a Monograph'for OTC Cold, Cough, Allergy, Bronchodilator and Antiasthmatic Products.” The proposed rule lays out the monograph for many ingredients used in common OTC cough/cold products including doxylamine succinate (e.g., NyQuil) and diphenhydramine hydrochloride (e.g., Benadryl). Among other things, the notice concluded that “[n]onnarcotic antitussives, such as dextromethorphan, act by selective suppression of the central cough mechanism and have no significant abuse liability.”

In the August 1987 final rule,4 FDA published the final monograph for antitussive drug products. In the monograph, DXM was labeled as a cough suppressant with directions for adults and children over 6 two years of age. The final rule provides two approved indications for DXM: temporary relief of cough from minor bronchial irritation and temporary relief of cough associated with a common cold.

To be clear, the efficacy evidence for DXM as an antitussive is still not strong. For example, in 2006, the American College of Chest Physicians gave DXM only a weak recommendation as an antitussive. Most OTC antitussives graded poorly.

DEA Regulation (Or Lack Thereof)

When Congress enacted the CSA, it scheduled nearly all known opiates and analogues. The CSA defines the term “narcotic drug” as including isomers of opiates. The law makes a special exception for DXM. Under 21 U.S.C. 811(g)(2), “[d]extromethorphan shall not be deemed to be included in any schedule by reason of enactment of this subchapter unless controlled after October 27, 1970 pursuant to the foregoing provisions of this section.” Thus, the CSA does not foreclose DXM being added to the schedules through the rulemaking process.

Several times, the federal government flirted with adding CSA controls to DXM due to reports of abuse. According to Erowid, recreational use dates back to the 1960s, almost immediately after DXM had been approved. As noted above, DXM abuse has been documented by law enforcement for decades. Today, teen use rate for DXM still hovers in the mid-single digits.

In 1990, FDA convened an advisory committee in response to citizen petitions from Pennsylvania and Utah due to reports of teen abuse. The committee ultimately determined that drug sponsors should provide additional and agreed to follow up in the six months after or when appropriate.

In 1992, the committee met again and reached no clear consensus. More data needed.

The FDA reconvened another advisory committee in September 2010 at the behest of DEA. As stated by the then-director of FDA’s Controlled Substances Staff:

Today we will discuss the abuse potential of dextromethorphan-containing drug products. And following the provisions of the Controlled Substances Act, the CSA, the Drug Enforcement Administration has gathered and reviewed available data on dextromethorphan abuse. DEA has reported to us increasing problems related to the drug’s abuse. In so doing, DEA requested a scientific and medical evaluation and scheduling recommendation for dextromethorphan from the Assistant Secretary for Health at the Department of Health and Human Services, HHS.

The responsibility for conducting the scientific and medical evaluation of substances for control under the CSA is delegated to the FDA. The National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIDA, participates with FDA on drug scheduling recommendations. The HHS scientific and medical evaluation is binding on the DEA insofar as our recommendation limits the level of CSA scheduling. DEA cannot place a drug into a schedule that is more restrictive than the one we recommend. Additionally, DEA cannot schedule a drug if our recommendation is that it not be controlled.

After receiving DEA‟s request for scheduling a recommendation on dextromethorphan, FDA began to collect information to support an agency assessment to respond to the request. A senior FDA attorney, Lynn Mehler, will today discuss the statutory and regulatory issues related to drug scheduling. The CSA regulations that result from scheduling are also in the background package. Dextromethorphan is extensively available in OTC products for the treatment of cough as well as in a number of prescription products.

The debate, its 354-page transcript, briefing documents, and slides are far too lengthy to do a blow-by-blow. Suffice to say, much of this essay summarizes what you’ll find in the source material. You are welcome to read it.

In the end, the Advisory Committee was torn. The members generally recognized some actual DXM abuse, but that the relative potential for abuse was lower than that of other drugs such as opiates. (Transcript pages 289-311.). In the end, the no votes took the day. Comments ranged from:

Yes: “the only means of restricting access to 19 this drug” and DXM “fits the description of Schedule V.”

Yes: “one of the only ways to decrease easy access to the target population that tends to abuse it.”

No: “I don’t think there’s any data to show that scheduling this drug necessarily decreases abuse.”

No: “[R]isk in minimal compared to the benefits of using it. And then when you compare it to other substances of 18 abuse, solvents, ethanols, cigarettes, prescription drugs, tobacco, natural substances, I think it’s minimal.”

Very qualified yes: “if we knew some of the data that would subsequently happen, it would make it a lot more comfortable of a vote.”

No: “scheduling wouldn’t solve all the problems” but “agree we do need to restrict the bulk and restrict the product to more than 18 years of age.”

Yes: “by the eight criteria for scheduling”

No: “the way they present it to support the effective scheduling was not strong enough” but recommend “follow-up of our decision so that 20 years from now we don’t come back saying that we wanted more data”

Yes: “we have a drug on the market targeted mainly toward pediatrics and we have -- we lack efficacy showing that this drug even works. I’d more interested in people putting their time and energy into doing clinical trials that would show -- give us some more data and it’s not even clear that it does that well in adults either. So limiting the drug, to me, wasn’t a problem if it’s not working, it’s just out there for the teenagers to get their hands on.”

No: “While I agree that it is perhaps not a very efficacious drug, I felt that that puts a lot of burden on people that have grown to count on it over the years”

No: “I feel like we’re in a bit of a time warp with the Controlled Substances Act trying to apply it to things that need a totally different kind of approach with the Internet and the way young people are being influenced to take drugs. And I think that the Controlled Substances Act is almost inappropriate for the present day.”

Yes: “I think that the information that was 6 available at the time the final monograph was determined did not have the awareness that we now have about the NMDA 8 receptor effects.”

No: “I think with all the discussion we’ve come to learn that this scheduling may have outlived its purpose for everything that we want to work around it.”

No: “I think that the drug does have risk for abuse and it’s important but limited in scope and in weighing the risks and benefits as scheduled. And I don’t feel that there was any evidence presented that suggested that 16 scheduling will reduce access to the target populations.”

Qualified No: “[I]f legislation passage is uncertain as we know and it doesn’t pass within a time frame, let’s say two years as CHPA says, then I would have changed my vote to yes and we should proceed with scheduling.”

Yes: “I believe that scheduling sends a message to the American public because right now they’re very calm and cool about -- and relaxed about the efficacy and the safety and the dangers related to this medication. I think they look to us to send a signal. And I think by not making a move today we send a signal to them.”

Yes: “I don’t want to go in the drug store a month from 6 now and see that it hadn’t been moved.”

Yes: “It’s abused by young people. It’s a gateway drug into PCP and a variety of other hallucinogens. There is no data that the current strategies are working. The medication itself has got very poor efficacy.”

No: “I think it would ultimately result in a tremendous lack of access whether people do not view things with double-blind 16 studies. They view it with their own practical experience. And again, we are asking people to self-treat on certain diseases.”

No: “I think that scheduling is a relatively drastic move to fix a problem that’s far from epidemic.”

No: “[S]cheduling is probably not going to be very effective in addressing this problem.”

No: “I think we need to have a scalpel to address the problem, not a big hammer. … I agree with Dr. Woods, perhaps the [CSA] covering this is no longer doing the job that it needs to.”

State Regulation

Despite lax regulation at the federal level, many states have implemented controls to restrict purchases by minors. Texas, for example, recently enacted a law preventing minors from purchasing DXM. Or in New York, if a retailer sells DXM to a minor, the retailer will owe a fine of $250.5

Three Disjoint Concluding Thoughts

So why did I write an essay on cough syrup? Well, in case you can’t tell, I see DXM as both a regulatory anomaly and teacher of sorts.

Many moons ago, I discussed how PCP—a drug with no currently accepted medical uses—remains in Schedule II. Inexplicably, it is easier to research PCP (Schedule II) than marijuana (Schedule I). Then, I explained that PCP being in Schedule II has almost certainly not resulted in the proliferation of PCP any more than there would be if the drug were in Schedule I. This is because, as we have repeatedly identified here at On Drugs, the only real difference between Schedule I and Schedule II is whether a drug is available for prescription. Since PCP no longer has an FDA approved indication, companies do not manufacture PCP for sale and doctors do not prescribe PCP. This raises the question of whether Schedule I is needed at all or if we can simply have a Schedule II populated with approved and non-approved compounds.

DXM takes this principle farther: the schedules as we know them may not be needed. Are we in a “time warp” with the CSA? DXM is not just available for purchase. It is hyper-available. Walk into nearly any drug store and one can pluck DXM from the aisle. True, DXM abuse is a thing. But the fabric of society hasn’t broken apart. And as noted above, states can add additional controls to DXM sales.

On Research…

Plenty of active pharmaceutical ingredients primarily developed to address cognitive disorders may have broader application. For example, research suggests the SNRI class of antidepressants may be useful in treating peripheral neuropathy. This should surprise no one. The body is a system of systems that all interact with each other.

Who knows what applications Schedule I compounds and analogues may have toward non-cognitive diseases, disorders, and conditions. Serotonin receptors, for example, play an important role in the gut. Hence, the “gut-brain” axis, that “gut” feeling, or “trusting your gut.”

[Aside: Anyone think research/psychedelic pharma too focused on Schedule I compounds and/or psychedelic therapy? Not knocking it, but the field is saturated. We don’t need 12+ companies researching psilocybin for every DSM condition, addiction, and cognitive disorder. The more lucrative business play—and perhaps what might get from lab to market quicker—is something along the lines of pill-a-day Auvelity™]

On Descheduling Marijuana…

Suppose finished cannabis products were legally available for purchase OTC at dispensaries. And set aside that this de facto occurs in much of America today. What happens?

DXM suggests that “not too much” is a possibility. Youth abuse probably does not change. Indeed, research points that way. And with state regulatory regimes, legalization likely leads to a situation where marijuana would still harder to buy than Robo. One cannot help but see certain parallels between marijuana/THC and cough syrup/DXM. Except marijuana/THC is likely more [edit: LESS] dangerous than cough syrup/DXM. Many of reasons behind the “no” votes from the DXM advisory committee equally apply to marijuana.

And yet, the feds are incapable of viewing DXM and marijuana through the same lens. The bias runs deep. The mantra holding back loosening federal regulatory controls on marijuana is always “more science.” Few utter this phrase for DXM to my knowledge, despite (1) clear, consistent evidence of youth abuse and (2) weak evidence of DXM’s efficacy—far weaker than supporting marijuana’s medical use and certainly not the type of evidence demanded for marijuana.

So why do the powers that be seem content with the science based on decades of use in the case of DXM but not marijuana? [Hint: One is a plant; the other is a molecule. One has a sordid, racist history; one was made in a lab.] Indeed, one could envision marijuana replacing codeine and other opiates as non-addictive pain relievers, no different than DXM/codeine and cough syrup:

On Microdosing…

DXM cough syrup/pills may be the OG microdose. I assume most have some understanding of “microdosing.” Generally speaking, as I use it, sub-perceptual or sub-hallucinogenic doses of a hallucinogen or psychedelic.

Long before the vernacularization of “microdose,” we had DXM. DXM hits hallucinogen territory as one nears 200mg. But the recommended OTC dose hovers around 15-30 mg three times a day—well below the threshold for hallucinogenic effects. In other words, microdose.

From this observation, consider two additional points.

First, the jury is out on microdosing in my view. There’s no clear rigorous evidence showing microdosing has health benefits. Some research suggests sub-perceptual doses of psychedelics doesn’t do very much. Other research may suggest potential benefit. Anecdotally, some people swear against microdosing. Others swear by it.

I’m neither doctor nor scientist. I just play both on the internet. In any case, I’m not taking sides. I’ll wait for better evidence before taking a position. Here, I only note that DXM suggests microdosing psychoactive compounds could have somatic, non-psychoactive applications at lower doses. At a low-dose, it is marketed as an antitussive. At a high-dose, it is a full-blown hallucinogen. Many microdose for supposed cognitive effects. But perhaps, microdosing can be used for effects completely unrelated to cognition, like cough suppression.

Importantly, these effects could be good—or bad. Whatever the case, since the populace is microdosing, researchers should to be able to do well-designed studies on the effects of microdosing free from unnecessary “time warp[ed]” regulatory barriers.

Second, to me, DXM shows that it isn’t impossible or nonsensical to envision or justify a future where microdoses of hallucinogenic compounds are available OTC—just like DXM—even if that future may be far, far away.

I am at Wonderland. Preferred pronoun: “he.” Preferred salutation: “your highness.”

Seriously, don’t.

I question the study design. DXM operates on different “plateaus” and 400 mg/70 kg is a fairly high dose. In contrast, a high dose of psilocybin is 40 mg/70kg or higher. Effectively, the researchers compared low-medium psilocybin doses with high doses of DXM. I would be more interested in a more apples-to-apples type comparison.

So in theory one could take about 30mg dxm a day for the mood boosting effect?

This was fascinating, but I really think you should proofread a little more. Lots of errors make for a challenging read.