In September, a Representative introduced “A Bill to Authorize Marihuana in the Treatment of Life- and Sense-Threatening Diseases.” It had bipartisan support. And it had broad support from physicians, lawmakers, and patients nationwide. Opinion polls showed that more than 75% of the country supported legislation to make marijuana available for the seriously ill.

When introducing his bill, the Representative explained, “[w]hile 32 States have adopted laws that allow supervised medical use of marijuana, federal agencies still define marijuana as a ‘drug with no accepted use in the United States’ and continue to prohibit marijuana’s medical application.” He continued, “I hope that through the passage of this bill, we can support these humane state efforts and bring relief to those who suffer from painful and sometimes terminal diseases.”

The Representative concluded his floor speech by explaining that “as a result of backward federal policies … many seriously ill Americans are being denied legal access to marijuana that could save their sight or even their lives. The public and the state legislatures have shown their overwhelming support for medical marijuana use. It is time for the federal government to act.”

In support of the proposal, the Republican Representative marshalled a litany of evidence showing that marijuana was useful in treating glaucoma. Such evidence went way back, including:

Historical records showing that marijuana was often prescribed for the relief of reading tension and eyestrain at the turn of the century through the mid-1920s.

The 1938 LaGuardia Commission noting the plant’s possible utility in the management of ocular disorder.

Clinical research from 1970 showing that smoked marijuana generated a consistent, dose related and clinically significant reduction in intraocular pressures.

The Representative also noted that more than half of persons undergoing chemotherapy did not obtain relief from synthetic THC, but that inhaled marijuana was 80% effective.

In November, the Representative responded to frequently asked questions, adding that while marijuana does not “cure” cancer, it

may help prolong the lives of cancer patients by allowing them to continue their potentially life saving chemotherapy or radiation treatments. The medical use of marijuana as an adjunct to anti-cancer therapies may also vastly improve the quality of life available to these patients.

His remarks quoted a National Cancer Institute memorandum noting the inadequacy of synthetic THC: “all in all the [marijuana] cigarette may be the best means of administering the drug.”

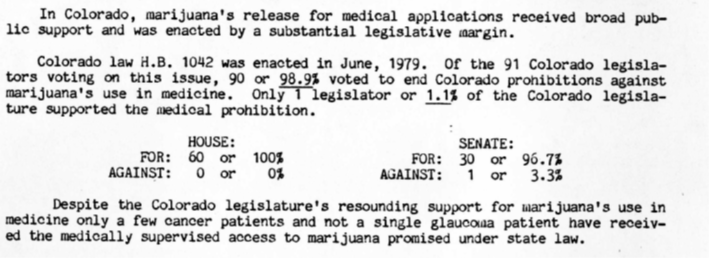

Behind the scenes, an advocate for the bill explained to congressmen that despite the laws in 32 states that made marijuana available to those who were “beyond the reach of conventional medical treatments”—laws that were enacted by “tremendous legislative margins”—federal agencies continued to prohibit marijuana’s medical use and through “bureaucratic mismanagement.” Take Colorado.

The Representative’s bill was hardly radical. It was basic human decency.

First, it moved marijuana from schedule I to II to allow patients with life- and sense- threatening diseases access to a substance that would help their pain. It did nothing to alter criminal sanctions applicable to marijuana’s non-medical use. Second, it created an agency in HHS responsible for manufacturing and distributing therapeutic marijuana to these patients. The scheme would have strictly complied with the requirements of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs concerning controls against diversion into nonmedical uses. Marijuana would only be distributed to hospitals or pharmacies at the request of physicians registered and licensed to distribute schedule II drugs. The controls would have been “as restrictive as those now imposed by the DEA on the distribution of other schedule II drugs,” like oxycodone, cocaine, methamphetamine, or fentanyl.

Finally, the bill dealt with the issue of FDA approval:

[T]he legislation exempts marihuana from FDA’s regulations governing “new drugs.” These FDA regulations were designed to test pharmaceutically prepared synthetic drugs and cannot adequately deal with naturally occurring medicants like marihuana. Moreover, patent problems, regulatory inhibitions, and marijuana’s present schedule I status make it impossible to advance cannabis through FDA’s complicated “new drug” procedures. Marihuana, in effect, “falls through the cracks” of existing FDA regulations.

The bill was quite popular. It garnered 84 co-sponsors—33 Republicans and 51 Democrats—including an ultra-conservative Representative from Georgia, who had helped lead the efforts. That is, until he visited with a former president and withdrew his support, explaining that while the scientific case for the medical use of marijuana was sustainable, the “cultural” case was not.1

The bill, of course, did not pass.

Fast forward almost fifteen years. A different Representative introduced H.R. 2618, “To provide for the therapeutic use of marihuana in situations involving life-threatening or sense-threatening illnesses and to provide adequate supplies of marihuana for such use.” Essentially the same as the 1981 McKinney Bill, Barney Frank’s 1995 bill legislatively put marijuana into Schedule II, complied with the Single Convention by creating an Office for the Supply of Internationally Controlled Drugs, and exempted medical marijuana from FDA regulations governing “new drugs.” It also had bipartisan co-sponsors, including prominent names like Nancy Pelosi.

The Frank Bill, of course, like the McKinney bill, went nowhere.

…I could go on.2

Earlier this week, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals poured out the Right to Try case. I’m privileged to be involved in the case led by Kathryn Tucker that I argued to the Ninth Circuit. You can read the opinion dismissing the case here. Jurisdictional dismissal was a known, high probability outcome when we filed the lawsuit. We were prepared for it. Two days after dismissal, we quickly pivoted and filed a petition to reschedule, citing the opinion, DEA’s position, and arguments in the lawsuit for why rescheduling is now required. Stay tuned.

The court’s opinion is well-reasoned. I believe the judges deeply considered our jurisdictional arguments, and faithfully applied Supreme Court and Ninth Circuit precedent to the facts as they saw them. They simply didn’t find our legal nuances and distinctions persuasive. Judge Sandra Ikuta authored an excellent opinion, which should surprise nobody, because she is a brilliant jurist.

But I would like to flag a comment she makes in footnote 13 dropped at the very end of the opinion, citing a pretty good piece by Mason Marks:

Supporters of decriminalization of psilocybin for therapeutic use have recognized that a legislative approach is necessary. In November 2020, Oregon passed Ballot Measure 109, which legalized psilocybin for therapeutic use, and several cities have made enforcement of psilocybin use low priority. Mason M. Marks, Controlled Substance Regulation for the Covid-19 Mental Health Crisis, 72 Admin. L. Rev. 649, 654, 708–10 (2020).

The footnote appears to suggest that a legislative approach is necessary to change psilocybin’s status under the CSA. Ironically, the Marks piece cited for that proposition details a different approach: rescheduling and de-scheduling.

As a general matter, I do not disagree with the footnote. Any lasting and systemic change will have to be accomplished through democratic processes and not the courts. But in light of the beginning of this essay, let me step back a bit and explain why I believe some lawsuits are necessary to get to that place—even if they may not always succeed.

First, to the extent one reads the footnote as a suggestion that a legislative approach is legally necessary to change the law so that DEA can accommodate psilocybin use by terminally ill patients, that is clearly wrong. One issue we briefed was DEA’s authority to grant a waiver or exception under the CSA. But even more clear is that the entire CSA was created as an instrument of agency discretion.

Congress put substances in schedule I, but then delegated rulemaking authority to the Attorney General not just to schedule more drugs, but to reevaluate the initial choices. That was what was supposed to happen with marijuana (but did not). There is a reticulated process for HHS and DEA to reschedule substances when times and knowledge change—both upscheduling or downscheduling. Rescheduling wasn’t an issue in AIMS, but even a cursory review of the legislative history shows that this was an essential feature of the CSA: to give the federal government a uniform framework and flexibility to schedule and reschedule drugs as needed, so that new legislation would not be required.

Sadly, this essential purpose of the CSA—flexibility—has been lost and has been replaced by a different paradigm: because Congress placed a drug in Schedule I in 1970, until a drug is approved by the FDA, DEA can’t downschedule drugs administratively. Congress must be the one to do it. This narrative was spun in the 1980s and early 1990s through the administrative process. A careful and honest review of the statutory scheme and the legislative history refutes it.

Clearly legislation is needed because the broader scheme is broken. Lawsuits have a role to play. While we lost the AIMS case, it is important to see what was gained. For starters, the case raised the awareness of a significant issue and framed the psilocybin debate on a national level in favorable terms. The court wrote a 26-page opinion that explains the legal problems faced by the terminally ill under the existing paradigm. Even if one believes that legislation is the solution, Congress can’t intelligibly craft solutions if it isn’t aware of the legal problems with existing paradigms. Litigation can tell a story help illustrate the problems and bring them out into the open. Even in defeat, these cases become small pieces of a bigger puzzle. Sometimes, they facilitate bigger next moves. We’re not done.

Equally important, there is also important value in reframing drug policy issues as a matter of agency discretion, which increases accountability. The Biden-Harris Administration could accommodate uses of psilocybin for the terminally ill. But perhaps, it just doesn’t want to (yet). More on that in a moment.

Second, and relatedly, is reframing the hard-to-shake pejorative narrative in any case involving drugs. Most drug cases are criminal cases, and many judges are former prosecutors. Both judges and the public often see drugs through this criminal law lens. There is thus value in bringing cases and stories that highlight the usefulness and benefits of these previously and sometimes unfairly maligned substances. Like medicalization, bringing worthy, high-profile litigation can be a part of an overall strategy of shifting the narrative.

Third, it is important for these constituencies to know that somebody is out there fighting for them—and fighting hard.

Finally, I return to where I began. Unlike everywhere else in society, at the federal government, sick, dying and vulnerable folks always seem to eat last—even in the most egregious, compelling, or heinous circumstances. There never seems to be any sense of urgency to help them.

As the above anecdote illustrates with the 1981 McKinney bill, support for providing marijuana in the treatment of life-threatening diseases was overwhelmingly popular. Nothing happened. Marijuana reform is overwhelmingly popular now, particularly medical. 91% of adults in the US favor making medical marijuana available. But little happens now other than appropriation riders that don’t quite do the trick. The situation reminds me of when Jon Stewart famously lambasted Congress over their failure to take care of 9/11 first responders.

In contrast, in 2016, the Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act, or the Marino Bill, which neutered DEA’s ability to seize suspicious shipments of opioids. That bill sailed through Congress. It unanimously passed by the Senate. And then two years later it reverberated across the political sphere. Then there is the Improving Regulatory Transparency for New Medical Therapies Act in 2014, which streamlined certain DEA processes for clinical trials and for FDA approved drugs. After a pharma company lost out on several years of patent protections due to agency delays, that bill also sailed through Congress.

So is 2022 the year where the federal government does something for those experiencing trauma, pain and sickness, independent of moneyed interests and political calculus, just because it is the right thing to do? Today, we have a president who has personally experienced trauma and deep tragedy many times over. President Biden wrote a book called “Promise Me, Dad” detailing some of these struggles. And then, during his 2020 campaign, President Biden promised us that if he were elected president, we would “see the single most important thing that changes America, we’re gonna cure cancer.”

Indeed, just yesterday, the President re-launched his “cancer moonshot” initiative, “committing the nation to working toward reducing the death rate from cancer by at least 50% over the next 25 years.” He announced the formation of a “Cancer Cabinet” with representatives from practically every arm of government. Both the President and Vice President Harris spoke about losing loved ones to cancer.

And yet, one year in, the Administration hasn’t done the single easiest thing that could aid cancer treatment and cancer patients who are dying and will die—improving access to medical marijuana (the plant) and marijuana (the plant) research. A war against cancer includes fighting the disease on all fronts. That fight includes not only looking for cures. It includes making sure that cancer patients get adequate relief in their suffering. Maybe the Administration is opposed to recreational or adult-use marijuana or psilocybin or whatnot. I’m not here to debate that today. Regardless of how one feels on that issue, I cannot think of any good reason why any virtuous person at this moment in history —let alone a person who has lost someone to cancer—would oppose improving access to marijuana, the plant, by those who need it by doing nothing of consequence to remedy the current untenable situation.

Marijuana reform (or reform involving controlled substances more generally) is a promising agent for relieving suffering for cancer patients. The evidence isn’t double-blind placebo Phase III clinical trial caliber, but is nonetheless overwhelming. Even if you took the extreme position that all marijuana is good for is getting high, what good argument can be made against letting terminally ill cancer patients in tremendous pain get high? And yet, marijuana reform doesn’t appear to be a part of the cancer moonshot. The Biden-Harris administration promised bare marijuana rescheduling from Schedule I to II. It hasn’t even done that.

That returns us back to the essential point of the essay and a major point of this newsletter. Federal drug law and the CSA isn’t a commandment Congress fixed in 1970 stone that the government is stuck with today and bound to follow. In fact, federal drug policy is a constant choice. Certainly, Congress can change the framework legislatively. But in 1970, Congress wrote the CSA to be flexible and capable of changing with the times and gave our government the tools to adapt federal law through the administrative process. Over time, however, that feature was forgotten.

So unlike vaccine mandates and other “executive order” type quasi-legislative initiatives, rescheduling marijuana or other substances is the one thing the executive branch can, without question, do unilaterally without the assistance of Congress. It is hardcoded into the CSA. Rightly or wrongly, the American people are souring on the Biden presidency. Mildly reforming drug policy—certainly delivering on easy campaign promises—isn’t just a decent thing to do, it is low-hanging political fruit.

But maybe the music isn’t in them. Or at least, not yet.

True to form, 15 years later, of course, Gingrich would sponsor the Drug Importer Death Penalty Act of 1996.