If you read this newsletter, it is no secret that Shane and I have pet obsessions with broken aspects of the CSA. Shane, for example, fixates on the Single Convention. Both of us harbor anger at how the crack house statute shuts down safe injection sites. But perhaps, no single issue draws more ire than DEA’s unlawful interpretation of “no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States.”

In this essay, I don’t want to cover that legal ground again. Instead, I want to go deeper and begin to explain why we care so passionately about this one issue and why, on a policy level, you should too. Or at least, a little bit.

This misinterpretation of the Controlled Substances Act stems from this outrageous 1992 decision and the MDMA hearings in 1987. But the gravity of the issue isn’t just about marijuana rescheduling, arcane points of administrative law, or basic principles of governance. It has become a central cast member in a battle for truth: where legislators invoke standards used to determine whether synthetic pharmaceutical products should be marketed interstate as an excuse to disregard overwhelming evidence showing that a plant that has been used safely for thousands of years and in turn, to avoid meaningful criminal justice reform and sensible drug policies.

To prove my point, the Minority View from the MORE Act, fresh off the desk of Jim Jordan, will be my muse. And in the process, I will drive-by comment on a few other matters.

The Minority Report

Like most cannabis legislation, the MORE Act is a deeply flawed bill. And I’m not talking about issues like social equity. I’m talking about basic legal stuff, like not dealing with pesky treaty obligations.

But the fundamental premise underlying the MORE Act—that cannabis should not illegal under federal law—is sound. How does the minority respond? Let’s look.

In a section entitled “Marijuana Usage” the minority view notes that “marijuana remains the most illicitly used drug in the United States and is cultivated in all fifty states.”

So what? In 2022, the federal government openly tolerates marijuana use through non-enforcement. Hence, unlike any other illicit drug industry, cannabis props up a multi- billion-dollar industry. Little wonder a drug the federal government openly tolerates through non-prosecution is “the most illicitly used drug in the United States.” We’re in ribbon cutting territory:

Regardless, that marijuana is the most “illicitly used drug in the United States” is a fact that favors regulation over prohibition. After all, a sizable portion of Americans holding productive jobs peacefully and regularly use cannabis “illicitly” with no adverse affects to anyone. Do we really want to make these folks subject to federal criminal sanctions? The fact that more people “illicitly” use is actually a reason to decriminalize. That’s how democracy usually works.

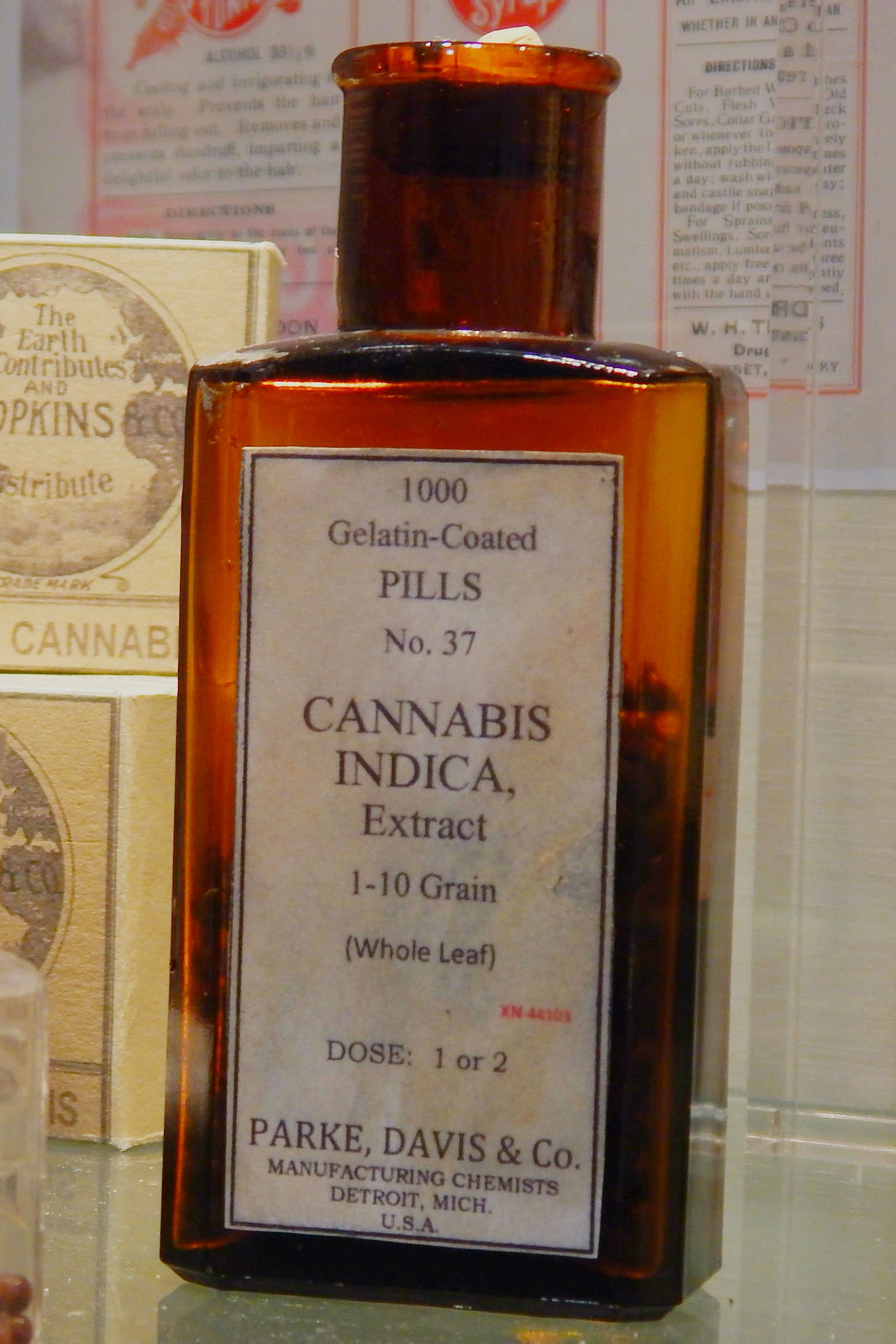

Next, the minority view claims that marijuana has been prohibited at the federal level since the 1937. That’s not quite right. Medicinal use of marijuana under the Tax Act was legal, but created a prohibitive tax on use and subjected it to extensive record keeping. Because of the Tax Act, prescriptions for marijuana precipitously declined. In 1942, the US Pharmacopeia dropped marijuana.

All this made it a whole lot easier for Congress, decades later, to put marijuana alongside drugs that had “no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States.”

The minority report then notes that law-enforcement agencies have reported that “a number of” marijuana businesses in these states have financial backing from “illicit revenue streams, including transnational criminal organizations.” As support, it cites DEA’s 2020 Threat Assessment. I cite checked this one—page 41 of the threat assessment. I was curious as to what data or evidence DEA cited to support the statement. There isn’t any. Just a string of high-level conclusory statements drawn from undisclosed law enforcement data.

Nonetheless, I don’t doubt DEA is correct. Certainly, many illegal marijuana businesses rely on illegitimate funding. Banking laws all but require it. But without the data or more specificity, it is hard to understand the magnitude of the “transnational criminal organization” problem.

More important, why is this so? Perhaps the Senate’s refusal to vote on SAFE Banking is a cause. Rather than obtain money through legitimate funding streams and capital markets, many marijuana streams are forced to the margins. SAFE Banking would fix many of these troubling issues.

Let’s pause to fully appreciate the dynamic here. The Democratic controlled Senate refuses to push SAFE Banking through. It could, but leadership prefers an all-or-nothing approach to cannabis reform. According to some, SAFE Banking benefits industry at the expense of equity and justice communities that have borne the brunt of prohibition. Probably true. So because SAFE Banking will not address social equity, best to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Reasonable minds can take either side of this debate. But those in favor of wholesale reform need to realize the consequences. And I would urge these organizations to carefully rethink their position.

As the minority report shows, holding up SAFE Banking fuels a powerful talking point—a talking point that holds up the very comprehensive reform bills like the MORE Act that these reformers would like to see. The minority uses the fact that marijuana businesses must rely on illegitimate sources of funding to paint the cannabis industry as tied to criminal organizations. Undoubtedly, someone has figured out that associating a multi-billion-dollar cannabis industry with “transnational crime organizations” is an effective rhetorical device to sour the middle on wider marijuana reform.

Not passing SAFE Banking helps perpetuate this madness. SAFE Banking isn’t just an incremental approach that could obtain bipartisan support and permit small business owners access to legitimate capital—including many minority business owners affected by the War on Drugs. It is a way to take away one of the rhetorical weapons used by those that oppose cannabis reform.

Of course, this point also remains: to the extent criminal organizations are associated with marijuana cultivation and distribution, perhaps that’s because cultivating and distributing marijuana is a crime. If the United States took the drastic step of criminalizing alcohol, criminal organizations would likely run the alcohol industry. By the way, that happened. According to the minority, however, federal legalization will create a legal market for marijuana, and will “inevitably lead to an increase in the trafficking of marijuana by criminal organizations in the underground market, estimated to be worth $40 billion or more in the United States.”

In light of Prohibition history, this claim might seem crazy. Actually, it’s not. Black markets continue—even thrive—despite cannabis legalization. One could persuasively argue that making cannabis more accessible creates a larger consumer class that increases demand in both legal and illegal markets. That effect may be compounded when a legal market is overtaxed or overregulated, driving the expanded consumer class to cheaper underground prices. The illegal California cannabis market is booming.

The issue isn’t about the claim. Rather, it isn’t based on a serious grappling with conflicting evidence. Science matters (see next section), except when it doesn’t. The preliminary research and evidence I’ve skimmed shows that recreational cannabis laws do have effects on the illegal drug market—but it’s complicated.

Equally important, the assertion doesn’t ask the right question. Suppose state level legalization leads to an uptick in the illegal market, as some evidence suggests, counter to our deeper intuitions. Why is that?

My suspicion is one of the very problems MORE is trying to solve—federal illegality —and specifically 280E. Section 280E of the tax code denies cannabis businesses important tax deductions. This, in turn, eats into the margins of cannabis companies and creates a floor on prices that state-legal businesses can charge. Drug dealers, of course, don’t pay taxes. And while I’m no economist, I suspect cannabis consumers buy from the illegal market because the price point is lower.

Once again, this is another instance where I think comprehensive reform advocates are thinking myopically and miss the mark in scorning an incremental approach. Even if 280E reform predominantly inures to the benefit of existing business, by squashing the illegal market, gutting 280E could actually help lay foundation for broader reform, including equity.

Next is the section entitled “PETITIONS TO RESCHEDULE MARIJUANA UNDER THE CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ACT.” This is our headliner.

In this section, the minority trumpets that fact that during the Obama-Biden Administration, DEA considered and denied petitions to reschedule marijuana. Why is this relevant to MORE? Well, the minority wants to convince you that that because HHS concluded in 2016 that marijuana “has a high potential for abuse, has no currently accepted medical use, and lacks an accepted level of safety for use under medical supervision,” removing marijuana from the CSA is a bad idea.

Don’t believe it. Here and elsewhere, we’re battling this fraud, which rests on an egregious misinterpretation of the CSA and a misapplication of basic principles of administrative law. Aside from “currently accepted medical use,” two other points.

Why did HHS conclude that marijuana has a “high potential for abuse”? Dig into the details of the HHS evaluation and be mesmerized by the data and the word “millions.” But in the end, the point isn’t more sophisticated than (1) individuals regularly use marijuana (2) that use is widespread and (3) vast amounts of marijuana are available for illicit use. In other words, Kafka logic. Marijuana has a “high potential for abuse” and remains federally illegal because (at least in part) the federally government tolerates its illegality and allows marijuana to proliferate.

DEA and HHS’s assessment of the third schedule I factor when it denied rescheduling—“lack of accepted safety for use of marijuana under medical supervision”—is just as farcical. All the agencies did was point back to the same facts and evidence that shows marijuana does not have a currently accepted medical use in treatment. It isn’t FDA approved.

In practice, according to DEA and HHS, the factual findings for Schedule 1 devolve into the following:

(a) Widely used

(b) Not FDA Approved

(c) Not FDA Approved

This application of the statute violates many of the most basic principles of statutory construction, including that Congress, like most people, doesn’t write such blatant redundancies into a statute.

I could law-nerd for several more paragraphs, but let’s cut to the chase. The federal government has distorted the rescheduling analysis to require FDA approval to show a drug or other substance is medically useful. Why is this important as a policy matter? A couple paragraphs later in the minority view, in the section “FLAWS WITH H.R. 3617”:

The MORE Act “disregards established science,” says the minority. Those are fighting words, and that leads me to my next and main point.

“Established Science” as Pretext to Avoid Criminal Justice Reform

“Established science” is the never-ending pretextual hang-up of Drug Warriors. It is the phrase many use to delude themselves into thinking that smoking cannabis cannot help veterans, those with chronic pain, or cancer patients. And I suspect it is what this Administration tells itself to avoid making any moves on cannabis. After five decades of science, we just need more established science.

The “established science” isn’t there (as opposed to the “unestablished science”?) because of how DEA and FDA define “established science” as it relates to marijuana. Science is, according to the dictionary, “a system of knowledge covering general truths or the operation of general laws especially as obtained and tested through scientific method.” But here, “established science” that would prove marijuana medically useful amounts to randomized Phase 3 clinical trials made with pharmaceutical quality, cGMP cannabis. As someone who works closely with the folks trying to do clinical trials with real-world cannabis used in dispensaries, let me tell you: it’s almost impossible. First, for decades it was a monopoly on NIDA cannabis. Through lawsuits representing Dr. Sue Sisley, we dismantled that roadblock. Now, with that roadblock removed, FDA won’t let studies with real-world cannabis proceed in clinical trials due to stringent cGMP criteria.

The regular science is everywhere. FDA could look at real-world data and real-world evidence in medically evaluating controlled substances. There is a Real-World Evidence Program after all. Real World Evidence is science. The real-world, non-clinical evidence supporting medical usefulness is overwhelming. Consuming all of it would make one vomit. A basic PubMed search for medicinal cannabis research yields thousands of papers since 2017. In 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine sifted through thousands of these abstracts and looked at the meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and studies. It found strong evidence in good-quality studies to show that there is conclusive or substantial evidence that cannabis or cannabinoids are effective for the treatment of chronic pain in adults, nausea and vomiting related to cancer chemotherapy, and symptoms of spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis.

Those that invoke science as an excuse not to follow through on cannabis reform are full of it or not looking. Scores of observational studies and millions of Americans that can attest to the medicinal benefits of the plant. And there is some clinical evidence to support the case too. Just look at the 2016 HHS evaluation that the minority report relies on. It went through clinical studies and concluded that they showed “positive results.” There’s an Appendix of them at page 53726. The studies on pain produced particularly promising results—even with the worst marijuana known to exist from the University of Mississippi. HHS ignored them, however, identifying “design issues” that should be addressed with “larger-scale” clinical studies to show safety and efficacy for a particular therapeutic use. Essentially, because these clinical studies weren’t done by Pfizer, they aren’t “established science” either. And because of various administrative law doctrines—some misapplied by the courts decades ago—you don’t get to dispute that point.

To be clear, requiring a drug manufacturer to produce randomized Phase 3 clinical trials made with cGMP cannabis may be a prudent and proper prerequisite to approving a pharmaceutical drug for interstate marketing. But this is the grand con: FDA approval to sell a drug is not what we are talking about. What we’re talking about is whether a criminal law, the Controlled Substances Act, should be revised by removing cannabis from control. Scientific evidence shows the drug isn’t dangerous. Scientific evidence shows it to be medically useful. People use cannabis everywhere. Nobody is dying. Is the fact that “established science,” i.e. late-stage pharmaceutical research, hasn’t proven that marijuana has a “currently accepted medical use in treatment” a valid reason to do nothing and wait ten years for more “science”? No.

Conclusion

And so I return to our pet issue: “currently accepted medical use” and the bogus five-factor test that equates “accepted medical use” with FDA approval standards.

If one wants to understand one of the core roadblocks with federal drug law and policy, this artifice is the starting point. True, the five-factor test is what DEA created and uses to avoid rescheduling marijuana. But this is more than a legal fetish. This issue runs deeper.

This is a distortion of truth. It is rhetorical cover for Drug Warriors. Going through the “minority view” above, it should be evident that there really aren’t many cogent arguments against legalizing cannabis. So Drug Warriors point to the absence of billion-dollar science to make claims that drug policy reform “disregards established science.” But of course, the science is there; it is just that the federal government does not consider it to be “established science.” Fund all the state law and local decrim- initiatives you want. Until we decouple drug control laws from the FDA approval process—this talking point will loom large. Worse, expect more do-nothing bad research bills that promise to deliver us “established science.” These research bills will suck the air out of the room and serve as pretext for postponing the actual reform urgently needed today.

If FDA standards are prerequisites for loosening draconian criminal controlled substances laws, the future of drug policy and criminal justice reform will be beholden to the pharmaceutical-industrial complex.