A Nine Plant Bust in Indian Country

Federal non-prosecution doesn't address "tangential enforcement"

News that three Bureau of Indian Affairs officers seized nine cannabis plants on indigenous land in New Mexico harkens us back to 2002 and the days of Gonzales v. Raich.

In Raich, DEA agents seized and destroyed six of Diane Monson’s cannabis plants in California. Monson, a medicinal cannabis patient with degenerate spine disease, grew her plants in accordance with California’s Compassionate Use Act. The Monson raid culminated in a Supreme Court showdown spearheaded by preeminent constitutional scholar Randy Barnett, where Monson and Raich (another patient) advanced a Tenth Amendment claim rooted in state sovereignty. They argued that the Controlled Substances Act’s prohibitions on manufacture and use of marijuana (21 U.S.C. § 841(a), 21 U.S.C. § 844) marijuana could not be validly applied to their purely local, intrastate conduct, which application would exceed Congress’s enumerated interstate commerce clause power. But the Supreme Court disagreed, holding that Congress had not exceeded that power because purely intrastate manufacturing and use was an economic activity which, in the aggregate, could affect the national market.

Federal Non-Enforcement

Federal law hasn’t changed since Raich. It is no more legal today under federal law to home grow marijuana for personal medical use under the CSA than it was for Diane Monson in 2002. And since federal law is the law of the land everywhere, growing marijuana for personal use remains an illegal activity in the United States.

While the law hasn’t changed, policy has—dramatically so. Four years following the Supreme Court decision in Raich, the Obama Administration adopted a policy of federal non-enforcement starting with the Ogden Memo in 2009. As a matter of prosecutorial discretion, DOJ determined it would not prosecute minor federal marijuana offenses in states that legalized and regulated marijuana. That policy rolled into President Obama’s second term with the Cole Memo in 2013. And in 2014, DOJ issued the Wilkinson Memo entitled “Policy Statement Regarding Marijuana Issues in Indian Country” applying the Cole Memo to “Indian Country,” extending non-enforcement to tribal lands governed by Native American tribes.

Then, starting in 2014, Congress began baking non-enforcement into law through an attachment to the Commerce, Justice, and Science Appropriations bill or “appropriation riders.” Commonly called the Rohrabacher-Farr Amendment (now called the also known as the Rohrabacher–Blumenauer amendment), these annually renewed riders prohibit DOJ from expending funds to prevent states from implementing their own medical marijuana laws. The text of the 2014 appropriation is as follows:

None of the funds made available in this Act to the Department of Justice may be used, with respect to the States of Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin, to prevent such States from implementing their own State laws that authorize the use, distribution, possession, or cultivation of medical marijuana.

Shortly after, in United States v. McIntosh, defendants indicted for marijuana crimes put the appropriations rider to the test. And the Ninth Circuit held that when the federal government prosecutes individuals for medical marijuana activity that is legal under state law, it prevents that state from giving practical effect to its laws that permit individuals to engage in that conduct. The rider prohibits DOJ from spending funds prosecuting individuals engaged in conduct permitted by state medical marijuana laws, because if it does, it necessarily must draw funds from the Treasury without authorization by statute, which would violates the Appropriations Clause of the United States Constitution.

Indirect or “Tangential Enforcement” by Other Federal Agencies

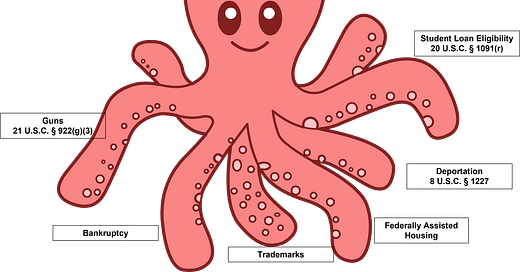

With a DOJ non-enforcement policy, an annually renewed appropriation rider, and fortunes being made off cannabis in broad daylight, a nine-plant government bust on tribal land might seem odd. But just because DOJ no longer prosecutes marijuana offenses as a matter of discretion does not mean marijuana law isn’t enforced. Federal drug law has its tentacles wrapped around the U.S. Code and affects all sorts of federal programs, policies, and agencies outside of federal prosecution.

This is why medicinal cannabis users can get kicked out of federal housing and can’t legally purchase guns (21 U.S.C. § 922(g)(3)). We call this concept “tangential enforcement”: when drug laws get enforced and implicated in ways other than direct criminal prosecution. Suffice to say, to fully appreciate the scope and impact of federal drug law in today’s world, this concept is critical to understand—and it is especially important if we care about equity. Non-prosecution addresses criminal prosecution, not tangential enforcement; and too often the burdens of tangential enforcement often falls on the shoulders of folks without power, money, or influence.

And it is in this concept that we likely find the answer to the question posed by the Picuris Governor: “why is Picuris being discriminated against or picked on?” Setting aside a “rogue officer” theory, I see two potential legal explanations.

First, these federal government policies and appropriation riders prohibit enforcement of marijuana laws by the Department of Justice, but not other agencies. The Bureau of Indian Affairs that seized the plants is in the Department of Interior, not Justice. And as far I know, no agency memorandum prohibits the Department of Interior from enforcing the CSA’s prohibition on marijuana, and the annually reupped Rohrabacher-Farr Amendment prevents Justice, not Interior, from expending funds from interfering with state marijuana laws. Hence, BIA’s response to the Picuris governor: “The BIA Office of Justice Services is obligated to enforce federal law and does not instruct its officers to disregard violations of federal law in Indian Country.”

Aside from removing marijuana from the CSA entirely, Congress could fix this problem by passing additional, broader, or stronger appropriations riders. The additional appropriations rider Congress is currently mulling over to specifically address the tribes, however, doesn’t address this gap. Consider language being proposed by Reps. Earl Blumenauer (D-OR), Tom McClintock (R-CA), Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) and Barbara Lee (D-CA) to be included:

None of the funds made available by this Act to the Department of Justice may be used to prevent any Indian tribe (as such term is defined in section 4 of the Indian Self Determination and Education Assistance Act (25 U.S.C. 5304)) from enacting or implementing tribal laws that authorize the use, distribution, possession, or cultivation of marijuana.

Same problematic language. The draft rider addresses funding to DOJ without addressing indirect enforcement conducted by every other federal agency, including BIA. (Someone should tell them.)

Second, the relationship between the federal government and the tribes is complicated and unique. The Supreme Court has long held “Congress has plenary authority to legislate for the Indian tribes in all matters, including their form of government.” United States v. Wheeler, 435 U.S. 313, 319 (1978). There is a general trust relationship between the federal government and tribes. United States v. Jicarilla Apache Nation, 564 U.S. 162, 174 (2011). And yet, tribes also retain a level of self-determination or tribal sovereignty to allow tribes to determine their own affairs. Tribes may have their own laws, law enforcement, and courts.

In the case of the nine-plant bust, the important point is that while tribes have a degree of sovereignty, they don’t have the same status as states in our republic. Due to the trust responsibility of the United States and the quasi-sovereign nature of the tribes, the relationship between tribes and the federal government is different and in some respects, the relationship more intimate; the United States is often more closely involved in tribal affairs, hence, a federal agency called the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Interior, the very agency that seized the plants. And of course, BIA has its own “Division of Drug Enforcement.” Tentacles.

Conclusion

The nine-plant bust serves as an important reminder that while we wait for Congress to enact broader marijuana reform, despite non-enforcement and many people profiting significantly in the industry, the little guy can and still does get screwed—just not directly and not by DOJ or DEA.

Special Note to Paid Subscribers

I want to issue a special thank you to everyone who has contributed to the newsletter. We’re grateful for those contributions, and as promised, we’ve used them to fund a request for archival documents. Stay tuned…